The ineradicably popular conception that Mozart's body was sewn into a linen bag, put into a reusable coffin with flaps on the bottom, and buried in a mass grave, is based on two memorable visual impressions. First, there is is the following scene from the motion picture

Amadeus.

Second, there is the following wooden exhibit in the "

Vienna Funeral Museum".

Of course, the iconic scene from the movie is already the result of a grave misunderstanding, created by poorly informed historians and authors such as

Volkmar Braunbehrens, who in his book

Mozart in Vienna, mixed together all kinds of second-hand information and turned it into a deeply flawed description of Mozart's burial "in a mass grave". The most fundamental misconceptions regarding this topic can be traced back to the

Josephinische Begräbnisordnung of 1784 (the burial regulations of

Joseph II). Joseph II (possibly motivated by severe mother-son-relationship issues) abhorred all kinds of religious pageantry and superfluous irrational customs, and, for the plain reason of sanitariness, wanted to shorten the decomposition time of buried bodies. Therefore, on 23 August 1784, he issued the following court decree.

- From now on, all crypts, cemeteries and graveyards which are located within the limits of villages shall be closed and instead only those should be used that are located outside the villages within reasonable distance.

- Following the last will of the deceased or the the wishes of the relatives all bodies should be carried to the churches by day or in the evening according to the regulation of burial fees and funeral cortege, be consecrated and laid to rest with the usual church prayers and then be brought by the parish priests to the chosen cemeteries outside the villages to be buried without ostentation.

- For these cemeteries a place of appropriate size is to be chosen which is not exposed to water and whose soil is not of a type that prevents decomposition. After the area has been selected it should be surrounded with a wall and adorned with a cross.

- Since the burial can serve no other pupose than to further the quickest possible decomposition, which is prevented by nothing more than the burial of bodies in coffins: thus it is commanded that the bodies should be sewn into a linen bag, completely naked and without clothes, then put into a coffin and be transported to the graveyard.

- In these cemeteries there should always be made a pit with a depth of six Schuh [one Austrian Schuh was 12,6 inches] and a width of four Schuh, the body should always be taken out of the coffin and put into the pit, as it is sewn in the bag, be covered with quicklime and immediately be covered with soil. In case several bodies arrive at the same time, they can be put into the same pit, but at anytime it is to be observed that every pit into which the bodies have been put be immediately filled and covered with soil, which must be continued in such a way that there is always a space of four Schuh between the graves.

- To cut expenses it has to be arranged that every parish acquires an appropriate number of well-made coffins of various sizes which must be provided to everybody for free; if somebody should provide his own coffin for his deceased relatives, he remains free to do this; but the bodies must never be put into the ground with coffins, but have to be taken out again to use the coffin for other bodies.

- Relatives and friends, who want to establish a special monument of love, admiration and gratefulness for the deceased, should be allowed to follow their desires; but these can only be erected at the walls not in the graveyards, to avoid taking up space there. (Joseph Kropatschek: Handbuch aller unter der Regierung des Kaisers Joseph des II. für die k.k. Erbländer ergangenen Verordnungen und Gesetze in einer sistematischen Verbindung, Johann Georg Moeßle, Vienna

1786, vol. VI, 565-70)

Paragraphs 5 and 6 of the 1784 Josephinische Begräbnisordnung in Kropatschek's collection of laws of Joseph II.

This is the theoretical legal situation on which all flawed descriptions in the Mozart literature about the composer's supposed burial in a bag and a mass grave are based. But the emperor's puritanical concept met with stark opposition, especially in Vienna where the local population had not forgotten the mass graves of the plague epidemic of 1713/14. To become effective in the

k.k. Hof- und Residenzstadt, a law had to be approved by the Vienna City Council. And because the citizens of Vienna filed massive protests against sack burials in mass graves, the Vienna Magistrate decided to remove the paragraphs 4-6 of the regulation from the

Currende (i.e. the official publication of the law). Therefore, reusable coffins only came into use in the

k.k. Erblande but never in Vienna. The general opinion of the Austrian people was nicely described by

Joseph Richter who, in his 1787 pamphlet

Warum wird Kaiser Joseph von seinem Volke nicht geliebt? ("Why is Emperor Joseph not being loved by his people?"), wrote the following.

Die Edlen im Volke wünschen, Kaiser Joseph möge überhaupt mit minder schädlichen Fehlern und Schwachheiten der Menschen etwas mehr Nachsicht haben. Unter diese Schwachheiten gehört die Abneigung, sich in Säcke einnähen, und dann durcheinander in eine Kalkgrube hinschleudern zu lassen.

The noble of the nation wish that Emperor Joseph would show a little more leniency towards the less harmful flaws and weaknesses of the people. Among those weaknesses is the reluctance against being sewn into a bag and then being tossed into the muddle of a lime pit.

Owing to the protest of the people, on 20 January 1785, obligatory burials in linen bags had to be revoked in the k.k. Erblande. Joseph II issued the following court decree which amounts to a veiled rant against the stubbornness of his own subjects.

Everybody is allowed to be buried in coffins.

Because His Majesty has noticed that, owing to the salutary order to bury dead bodies without coffins in linen bags, sewed in completely naked and without clothes, many minds have been troubled and – out of prejudice – burials of bodies together with coffins are being preferred; and His Majesty is not inclined however to bend the will of his subjects in this less significant matter which is irrelevant for the general welfare: therefore His Majesty has declared that he does not think of forcing somebody to this kind of burial, who is not convinced of its advantage, but is willing, as far as the coffins are concerned, to allow everybody to freely do what in advance he considers agreeable for his body. Apart from that the content of the regulations of 23 August of last year remains valid. (Kropatschek, Handbuch 1787, vol. VIII, p. 675f.)

The Emperor's withdrawal of obligatory burials without coffins in vol. 8 of Kropatschek's collection of laws.

The documents concerning the expenses for Mozart's coffin are lost. But there are, of course, archival sources from Mozart's time that show as to how the procurement of a coffin for a common citizen was handled and how much it cost.

When Mozart, in June 1788, moved into the house

Alsergrund No. 135, he made the acquaintance of Christoph Dopler who lived there in a small apartment on the first floor, together with his wife Magdalena, née Neu, and their youngest two children Maria Anna, and Karl.

Christoph Dopler in the 1788 tax register of the house Alsergrund 135. His neighbor, the shoemaker Peter Dußel, signed as witness in Dopler's probate documents (A-Wsa, Steueramt B34/27, fol. 218).

Dopler was born on 25 December 1737, in

Loosdorf in Lower Austria (

Loosdorf 2, 255). At the time of his wedding in 1764 (

St. Ulrich 25, fol. 188v), he was referred to as "soon-to-be innkeeper". In 1769, he was described as "former innkeeper in the cemetery of the Benedictine friars of Montserrat" on the Alsergrund, (which was closed in 1783). In 1771, in the baptismal entry of his daughter Regina (

Schotten 37, fol. 223v), he is documented as working as

Goldpolier (gold polisher) at the

porcelain factory, and in 1773, on the occasion of the baptism of his daughter Theresia (

Schotten 38, fol. 64v), he is already given as "Mahler in der

Porcellain Fabrique" (painter at the porcelain factory in the suburb of

Rossau). Dopler's speciality was painting the so-called

Türkenbecher (turkish cups) most of which were exported to the Levant (F. A. Schrämbl,

Merkwürdigkeiten der Welt oder vorzügliche Erscheinungen der Natur und Kunst, Vienna 1811, 82).

Christoph Dopler's seal and signature in the marriage records of his friend Andreas Kuhrmayr who ran an inn in the house Alsergrund 135 (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A3, 217/1787)

Dopler died on 5 May 1789 (

Wiener Zeitung, 13 May 1789, 1213), in the house Alsergrund 135. His probate records are of great interest, not only because they contain a document related to the cost of Dopler's coffin (directly proving the use of coffins in Mozart's Vienna), but they also contain a list of expenses of Dopler's widow which document Constanze Mozart's private funeral expenses two years later which are not extant in Mozart's

Sperrs=Relation. Dopler's body was consecrated at the

Servite parish church in Rossau and buried third class for six Gulden and forty-five Kreuzer in the

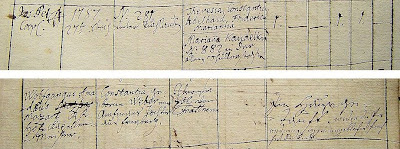

Währinger Allgemeiner Friedhof. The carpenter who made the coffin wrote the following receipt (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 1770/1789).

Quittung

P[er] Ein Gulden dreisig Kreitzer welcher ich / Endes under schribener vor eine thotten / druchen vor den herrn Cristof Doppel Seliger / Richtig und bar empfangen habe bescheine / hie mit wienn d[en] 12 Meÿ 789

Joseph Haiss bürgl: / Dischler meister

Ites[t] 1 f 30 x

Receipt

For one Gulden thirty Kreuzer which I the undersigned have received exactly and in cash for a coffin for the deceased Mr. Christoph Dopler, I certify herewith. Vienna 12 May 1789

Joseph Haiss civil master carpenter

That is 1 f 30 x

It must be noted that Dopler was not a wealthy individual. His modest estate was estimated at a value of about 34 Gulden. The cost of Dopler's coffin equalled the estimated value of his wall clock. The coffin cost six Kreuzer less than the cowl in which Dopler's corpse was dressed. The following list of Magdalena Dopler's private burial-related expenses provides a fascinating look at the burial customs in late eighteenth-century Vienna. In December 1791, Constanze Mozart – except for the orderly's wage – was certainly faced with having to pay for exactly those items. The list of her expenses, which survives in Mozart's probate records ("bezahlte Konti"), only concerns the composer's most recent debts.

The list of Magdalena Dopler's immediate expenses concerning her husband's burial (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 1770/1789).

What follows is yet another document from the year 1790 that proves the use of coffins in Vienna. On 8 May 1790, Christina Ponschab, first wife of the court singer Leopold Ponschab (1742–1795), died at Spittelberg 135 (today

Burggasse 2). Her probate file contains a list of medical and burial expenses that her widower had to cover. Listed among these objects is a "Todten Trugen" (coffin) for four gulden.

The list of Leopold Ponschab's expenses concerning his wife's medical treatment and burial (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 1613/1790)

The historical facts can be summarized as follows:

- Mozart was not buried in a linen bag without a coffin, because such burials were never mandatory in Vienna.

- Mozart was not buried in a mass grave, but in a customary "allgemeines Grab" (the usual common grave).

Of course, countless books on Mozart – and even the most recent ones – are rife with stories about Mozart's body having been sewn into a bag and mercilessly hurled into a mass grave. Most of this nonsense is based on Braunbehrens, who in his 1986 book, not only fantasized about "the music that was performed at Mozart's consecration inside[

sic!] the

Kreuzkapelle of St. Stephen's" (there was no music and the consecration took place outside the church), but also referred to "rental coffins having been the normal equipment of all parishes" (a claim that he of course corroberated with the notorious

Klappsarg in Vienna's

Bestattungsmuseum). Let us look at some of the most typical examples from the recent literature. To nobody's surprise, Maynard Solomon picked up Braunbehrens's error and described the idea of "being buried without a coffin" for Mozart to have been "a metaphor of the brotherhood of souls". In volume 2 of his

biography of Joseph II,

Derek Beales (as of 2013) erroneously claims that between 1784 and 1785, people in Vienna were "buried without coffins in mass graves". In her book

A History of Opera,

Carolyn Abbate states (among many other falsehoods about the composer) that "Mozart was buried in a mass grave". Mozart biographers do not fare any better.

Martin Geck firmly believes that "Joseph II spartan burial regulations were still valid in 1791", and so does

Piero Melograni. In his 2009 book on Mozart's finances,

Günther G. Bauer describes Mozart as having been buried "in the dead of night[

sic!] in the usual mass grave". In 2009,

Annette Kreutziger-Herr promised to answer the important question whether "Mozart was buried in a pauper's grave", only to claim again that Mozart's burial was not an exception and that "

he was sewn into a linen bag". In her 2012 book about Constanze Mozart,

Gesa Finke described Mozart as "laying out in a simple reusable coffin" and being buried "wrapped a linen sheet in a mass grave". And yet, in her 2012

biography of Emanuel Schikaneder,

Eva Gesine Baur definitely takes the cake. After having allegedly spent "a year and a half of research", she not only has Mozart buried with a reusable coffin (with flaps on the bottom), but also chooses to honor Schikaneder with the exact same funerary procedure in the year 1812. Baur's text sparkles with stunning ignorance.

For Mozart, his friend van Swieten had ordered a third-class burial with the smallest cortege[sic!], certainly not impious, but common with the majority of the populace and also sensible, considering the financial situation of the widow. Schikaneder is also buried in the third class, like Mozart in a coffin that is opened at the bottom, emptied into a shaft grave and used again, just as Emperor Joseph II, the enemy of la pompe funèbre would have liked it. Swieten[sic!] or Constanze had however rented a carriage with two horses to avoid a mass transport.

Only a few remarks concerning this paragraph will suffice. A burial "mit dem kleinsten Geleit" is a misnomer caused by a misunderstanding. The term "kleinstes Geleit" did not exist in 1791. The correct term was "dritte Class". The Viennese dialect term "Geleit" did not refer to a

Geleit (cortege), but to the

Geläut (peal of bells). Baur's claim that "Schikaneder received a third-class burial" is not based on any documentary evidence. At the time of Schikaneder's death in 1812, the burial classes of Mozart's days did not exist anymore and had long been replaced by a new

Stolordnung (regulation of burial fees). Since the parishes of the suburbs had always lower burial fees than the parishes in the City, a comparison in this case is not possible anyway. There is no source that documents the costs of Schikaneder's burial on 23 September 1812 (

Pfarre Alservorstadt, Tom. 6, fol. 53). He was probably buried "5. Rubrik 3. Klasse", but this category allowed for various extra expenses that were paid apart from the parish fee, such as the cortege and expenses for an own grave. The fact that on 29 September 1812, at 10 a.m., Mozart's

Requiem was performed for Schikaneder at St. Joseph ob der Laimgrube, which was the parish church of the Theater an der Wien, should make us reconsider the idea of Schikaneder having been buried without any effort and completely neglected by his former colleagues.

It is true that in 1791, for three gulden, a carriage was rented for the transport of Mozart's body to St. Marx, but there is no documentation concerning the number of horses that pulled this carriage. That there were two of them is a figment of Baur's blooming imagination. Similarly untenable is Baur's claim that without this carriage Mozart's body "would have become part of a mass transport". Since on 6 December 1791, Mozart was the only person to receive obsequies at St. Stephen's, to be buried in St. Marx, there was no possibility of several corpses being transported to this cemetery on one carriage. All the other deceased persons that were registered in the Cathedral's

Bahrleihbuch on this day were either consecrated in other parish churches or buried in other cemeteries, such as Währing or Matzleinsdorf (

A-Wd, Bahrleihbuch 1791, fol. 337r-

338v).

© Dr. Michael Lorenz 2013. All rights reserved.

Updated: 24 April 2025