In 1781, Mozart spent most of his name day, Wednesday, October 31, in the house of Baroness Waldstätten in the Leopoldstadt. He got there just after noon, and was probably still with the Baroness, when, at 11 p.m., he was surprised by a group of six musicians who began playing his Serenade K. 375 in the courtyard of the house. On the following Saturday, November 3, 1781, Mozart described the events of that day in a letter to his father.

The first page of Mozart's letter of 3 November 1781 to his father (A-Sm, BD 638)

Mon trés cher Pére! Vienne ce 3 de 9bbre 1781It is possible that Mozart spent the night at the Waldstätten house and that this surprise serenade took place in the Leopoldstadt.

Forgive me for not having acknowledged at last post day the receipt of the cadenzas, for which I thank you most sincerely now.—It happened to be my Name Day — so in the morning I did my Prayers and then, just as I was about to write to you, a whole bunch of well-wishers invaded my room — then at 12 noon I took a carriage out to Leopoldstadt to visit Baroness Waldstädten — where I spent the rest of my Name Day. At night, at 11 o’clock, I was treated to a serenade of 2 clarinets, 2 horns, and 2 bassoons — which as it so happens was my own composition. — I had composed it for St. Theresia’s Day — for the sister of Frau von Hickl, or the sister-in-law of the court painter Herr von Hickel, at whose house it was actually performed for the first time. — The 6 gentlemen who performed it are poor devils who, however, played quite well together, particularly the first clarinetist and the two horn players. — The main reason why I had written the serenade was to give Herr von Strack, who visits there daily, a chance to hear something that I had composed; for that very reason I had put a little extra care into the composition; — and indeed, it was very much applauded. — During St. Theresia’s night it was performed at three different locations — they had no sooner finished playing in one place than they were asked to play it somewhere else — and for money, too. At any rate, these night musicians had asked for the doors to be opened and, after positioning themselves in the courtyard, they surprised me, just as I was getting undressed, most agreeably with the opening chord of E-flat.

Mozart's room at Stadt 1175

From late August 1781 until July 1782, Mozart's city residence was a single room on the fourth floor of the house Stadt 1175 (today Graben 17) where he was a tenant of Theresia Contrini and her brother-in-law Jacob Joseph Kesenberg. After an earlier owner, Contrini's father, the Stadttändler Mathias Jagschy (1689–1761), the building at that time was called "Jaggisches Haus". Here Mozart wrote "Die Entführung aus dem Serail". This house was demolished in 1905.

The house Graben 17 (former conscription Nos. 1175/1213/1145), where Mozart lived from August 1781 until July 1782 (photograph by August Stauda from before 1904, Wien Museum I.N. 24119). It is a curious coincidence that Mathias Jagschy and Theresia Contrini were best friends with Simon Zach, the father of the master builder Andreas Zach who in 1787 designed the Theater im Freihaus. In 1738, Jagschy was Andreas Zach's godfather. The alleged birth date of Andreas Zach (25 September 1736) given in the literature is wrong and based on an error by Felix Czeike. Andreas Zach was not the son of a tripe cooker (A-Wd, 70, fol. 12v), but of the bricklayer Simon Zach, who had been born in 1709, in Heidenreichstein (Heidenreichstein 3, 318). Andreas Zach was born on 30 November 1738, in Vienna (A-Wd, 71, fol. 167v). The godparents of his sister Maria Anna Christina Theresia in 1747 were the Jagschy and Contrini couples (A-Wd, 77, fol. 58r).

Mozart's room was located on the fourth floor behind the courtyard. The fifth floor, where Rupert Pokorny's photo studio (visible above) was to be located, was added in July 1888. For the purpose of this addition, which was commissioned by the house owner Bernhard Hirsch, a plan of the fourth floor was drawn up. On this plan Mozart's room is very easy to identify: it is the only single room beside a chimney, with a window to the courtyard, and its own access from the stairs. The dimensions of this room were 3.6 x 4.3 x 3.4 x 4.3 meters, with the floor area being about 14.9 square meters. The door to the left of the room, visible on the plan, was obviously a later structural change, as the small individual room turned out to be unrentable at a certain point.

A plan of the fourth floor of Graben 17 from 1888, with Mozart's single room marked with a red M. The design of the window of the projected photo studio on top of the house is visible at the top right (A-Wsa, M.Abt. 236, A16 - EZ-Reihe: Altbestand: 1. Bezirk EZ 394). The glass roof of Pokorny's photo studio is visible on a photograph by August Stauda from around 1890: Wien Museum, I.N. 32614/1.

Walther Brauneis's claim that at this address Mozart was a tenant of Adam Isaac Arnsteiner, is not supported by any source (Brauneis 1991, 325). The mistaken concept that Mozart had close relations with the Arnsteiner family is based on Volkmar Braunbehrens's imagination (Braunbehrens 1988, 76f.) which seems to have been inspired by Hilde Spiel's biography of Fanny Arnstein (Spiel 1978, 119f.). The erroneous claim that Fanny Arnstein "was Mozart's landlady for eleven months beginning in August 1781" has even soaked into the more recent Mozart literature (Wolff 2012, 59). The relevant entry in the 1788 Josephinische Steuerfassion shows that Mozart's room was let by the house owners. Rent for Mozart's room was a modest 100 gulden a year.

Mozart's room ("10 Ein Zimmer u Keller Eigenthümer 100 [gulden]") on the fourth floor of Stadt 1175 listed in the 1788 tax register (A-Wsa, Steueramt B34.5, fol. 216).

Braunbehrens thought that Contrini lived in the single room No. 10 which was actually Mozart's (Braunbehrens 1988, 76). Theresia Contrini does not appear in the 1788 Steuerfassion, because she died on 21 October 1787 (Wiener Zeitung, 27 Oct 1787, 2615). In 1781, Contrini had lived in the five-room apartment No. 8 on the fourth floor, which in 1788 was rented by the Italian valet Johann Biglietti. This is documented by an announcement in the Wiener Zeitung concerning the auction of Contrini's belongings on the fourth floor of Stadt 1175 (WZ, 27 Nov 1787, 2864)

A certificate of employment, written on 18 September 1787, by Nathan Arnsteiner's brother-in-law Salomon Lefmann Hertz (1743–1825) for his chambermaid Antonia Moringer (b. 4 June 1761 [Fallbach 2, 180], here misspelled "Morgener"). This document was also signed by Mozart's former landlady Theresia Contrini as "Haus Frau von Nomer 1175" (A-Wstm, St. Peter, VKA 75/1787).

A description of the old building survives in an appraisal of Stadt 1175 from 1787. The passage concerning the yard in this evaluation reads as follows:

Ebener Erde Von dem Graben eine Gewölbte Einfahrt, ein kleiner Hof, der Bumpenbrunn unter dem Gebäude, die S[ub] v[oce] Priveter auf dem Canal, von disem Hof durch eine Gewölbte Wagenschopfen ein Außgang in ein kleines Lichthöfl. Am Gebäude Befindet sich 3 Gewölbte Stallungen, wovon einer auf 6, einer auf 4, einer auf 2 Perth, 3 kleine Heügewölber, 2 Handgewölber, 2 Gewölber jedes mit dopelten Außgang.[translation:]

On the ground floor from the Graben a vaulted entrance, a small courtyard, the pump well under the building, the so-called Priveter [toilets] above the canal, from this courtyard through a vaulted wagon shed is an exit into a small atrium. The building has 3 vaulted stables, one for 6, one for 4, one for 2 horses, 3 small hay vaults, 2 hand vaults, 2 vaults, each with a double exit.

The Inventur=Schätzung of Stadt 1175 from 30 November 1787, signed by a builder, a carpenter, and a stonemason, which contains a description of the structural condition of the building (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 2583/1787).

In my opinion, it is rather unlikely that at 11 p.m., in an October night, a janitor would have allowed six players of wind instruments into a courtyard in the city where their performance would have woken up the entire neighborhood.

The Waldstätten house

Baron Hugo Joseph von Waldstätten's house Leopoldstadt No. 360 was located on the Prater Straße (last numbering 518, today Praterstraße 15). On 10 April 1777, Baron Waldstätten had bought this house from the merchant Joseph Wurmscher, together with a garden of approximately 1963 square fathoms (7685 m2). On 30 March 1778, Waldstätten received the Gewähr (guaranty of ownership) for this property (A-Wsa, Grundbuch 106.19, fol. 149v).

The entry in the land register concerning the guaranty of ownership of the

house Leopoldstadt 360 for Baron Hugo Joseph von Waldstätten (A-Wsa, Grundbuch 106.19, fol. 149r)

Baron Hugo Joseph von Waldstätten's house Leopoldstadt No. 360 on Huber's 1778 Vogelschauplan of Vienna (W-Waw, Sammlung Woldan). Until 1785, the adjacent house No. 359 belonged to Giacomo Tramontini, the widower of Vittoria Tesi Tramontini.

A register from 1786 shows the houses Leopoldstadt 359-361 and their owners Jakob Tramontini, Hugo Joseph Baron von Waldstätten, and Johann Frischherz. Waldstätten is described as "former civil merchant" (Fischer 1786, 146). Contrary to what the Mozarteum states in the English translation of Mozart's letter, Baron Waldstätten was never an administrative official. His titles Truchseß and "der N. Ö. Land Rechten Beÿsitzer", which are documented in the entry concerning his wedding on 3 August 1762, at the Schottenkirche (Schotten 31, fol. 146v), were related to honorary functions connected with his status of nobility and his membership in the Lower Austrian Landstände.

The houses Leopoldstadt 359-361 and their owners in a register from 1786 (Fischer 1786, 146).

In 1778, the house Leopoldstadt 360 consisted of two floors with two side wings and was open toward the garden. Between 1778 and 1786, Waldstätten had the building's courtyard closed by adding a rear wing to the house. In June 1786, Waldstätten applied to the municipal Unterkammeramt for permission to add a partial third floor to his house on the street side.

In the summer of 1788, the addition of a third floor to the house was still not finished, because the Josephinische Steuerfassion (municipal tax register) states "Der 2te Stock. stund in Bau" (the 2nd floor was under construction). The Steuerfassion also lists the 18 rooms, chambers, and cabinets on the second floor that can be seen on the plan above.

On 30 November 1792, the house Leopoldstadt 360 was put up for auction and sold to Countess Josepha Theresia von Harrach, née Baum von Appelshofen, wife of Ferdinand Johann Nepomuk von Harrach (A-Wsa, Grundbuch 106.20, fol. 184v). The rear part of the third floor was added in 1793 on behalf of Countess Harrach.

In 1797 the house was bought by Count Karl von Esterházy (A-Wsa, Grundbuch 106.21, fol. 36r).

The Strack-Hickel-connection

Mozart's main reason for writing the serenade K. 375 was to try to improve his reputation as a composer with the emperor through the imperial valet Kilian Strack. As Karl Maria Pisarowitz put it: Mozart wanted to use Strack as an "anti-chambre springboard into the musical corner of the monarch's heart" (Pisarowitz 1960, 5).

On 21 February 1758, the court informed the cameral directorate that Strack had been employed with an annual salary of 1000 gulden.

In 1760, Strack applied for a court quarter ("Hofquartier") in the Sattlerisches Haus in the Kärntnerstraße, which he was granted on 27 November 1760.

A plan of the second floor of Waldstätten's house from June 1786 (A-Wsa, Unterkammeramt A33, Alte Baukonsense 3126/1786)

In the summer of 1788, the addition of a third floor to the house was still not finished, because the Josephinische Steuerfassion (municipal tax register) states "Der 2te Stock. stund in Bau" (the 2nd floor was under construction). The Steuerfassion also lists the 18 rooms, chambers, and cabinets on the second floor that can be seen on the plan above.

The entry concerning the house Leopoldstadt 360 in the 1788 Steuerfassion (A-Wsa, Steueramt, B34.7, fol. 79).

On 30 November 1792, the house Leopoldstadt 360 was put up for auction and sold to Countess Josepha Theresia von Harrach, née Baum von Appelshofen, wife of Ferdinand Johann Nepomuk von Harrach (A-Wsa, Grundbuch 106.20, fol. 184v). The rear part of the third floor was added in 1793 on behalf of Countess Harrach.

The plan for the completion of the rear part of the second floor of Leopoldstadt 360 in 1793 (A-Wsa, Unterkammeramt A33, Alte Baukonsense 4146/1793)

In 1797 the house was bought by Count Karl von Esterházy (A-Wsa, Grundbuch 106.21, fol. 36r).

The Strack-Hickel-connection

Mozart's main reason for writing the serenade K. 375 was to try to improve his reputation as a composer with the emperor through the imperial valet Kilian Strack. As Karl Maria Pisarowitz put it: Mozart wanted to use Strack as an "anti-chambre springboard into the musical corner of the monarch's heart" (Pisarowitz 1960, 5).

The first page of Mozart's wind serenade K. 375 with the E-flat major chord at the beginning that gave Mozart a pleasant nightly surprise (D-B, Mus. ms. W. A. Mozart 375).

Since Strack was close friends with the family of the court painter Joseph Hickel and was a regular guest at Hickel's home, Mozart took St. Teresa's Day (October 15) as an opportunity to write a six-part wind serenade for Hickel's sister-in-law. It seems that the original scoring of K. 375 for only six instruments was caused by the fact that Mozart had no amateur oboists available for the strolling performances of the piece.

Johann Kilian Strack

Johann Kilian Strack was baptized on 30 March 1724, in the church of St. Emmeram in Mainz, son of the barber and surgeon Johann Strack (Pisarowitz 1960, 5). In 1960, Karl Maria Pisarowitz published a short article on Strack, which he called a "study", but which – as was usually the case with Pisarowitz – was a somewhat oddly phrased summary of his correspondence with various parish priests and archivists. While Pisarowitz did not have much to say about Strack's early years and described Strack's first wedding as "inscrutable", some newly found sources shed more light on Strack's biography. When Strack entered imperial service in 1758, he had already been employed in Vienna for several years as valet to Prince Karl Johann von Dietrichstein. Strack owed his career in aristocratic service in Vienna to Count Johann Anton von Pergen, who, while serving as imperial envoy in Mainz, had recommended Strack to Prince Dietrichstein. In late 1757, Princess Dietrichstein recommended Strack to Empress Maria Theresia, who in 1758 hired Strack as valet to "the 4th Most Serene Prince", Archduke Ferdinand. Strack's employment in the imperial household began on 15 January 1758. The course of events is documented in the following letter which Strack wrote to Count Pergen on 18 January 1758.

Johann Kilian Strack

Johann Kilian Strack was baptized on 30 March 1724, in the church of St. Emmeram in Mainz, son of the barber and surgeon Johann Strack (Pisarowitz 1960, 5). In 1960, Karl Maria Pisarowitz published a short article on Strack, which he called a "study", but which – as was usually the case with Pisarowitz – was a somewhat oddly phrased summary of his correspondence with various parish priests and archivists. While Pisarowitz did not have much to say about Strack's early years and described Strack's first wedding as "inscrutable", some newly found sources shed more light on Strack's biography. When Strack entered imperial service in 1758, he had already been employed in Vienna for several years as valet to Prince Karl Johann von Dietrichstein. Strack owed his career in aristocratic service in Vienna to Count Johann Anton von Pergen, who, while serving as imperial envoy in Mainz, had recommended Strack to Prince Dietrichstein. In late 1757, Princess Dietrichstein recommended Strack to Empress Maria Theresia, who in 1758 hired Strack as valet to "the 4th Most Serene Prince", Archduke Ferdinand. Strack's employment in the imperial household began on 15 January 1758. The course of events is documented in the following letter which Strack wrote to Count Pergen on 18 January 1758.

Monseigneur!

Je prens la liberté, demander a votre Excellence que dimanche passé j'eu le bonheur d'entrer a la Court en qualité de valet de Chambre de S[on] A[ltesse] R[oyale] L'Archiduc Ferdinand. c'est a votre Excellence, que je dois ce bonheur, puisqu' Elle m'a fait la grace de me placer dans une Si grande et bonne Maison, que celle du Prince de Dietrichstein. l'Envie, que j'avois toujours, de bien servir, et non pas mes merites ont engagé Madame la Princesse, deme recommender a S[a] M[ajesté] L:' Imperatrice avec tant d'emphase que j'ai en le bonheur, d'etre preferé, a un foule de Competiteurs. Maintenant je n'ai plus rien a desirer. Monseigneur! que de pouvoir persuader votre Excellence a croir, que je sens la plus vive reconnoisseur des bontés, qu' Elle a en pur moy, et que je n'oublierai jamais les graces qu' Elle a bien voulu me faire; Si j'ai tardé jusqu'ici a en faire de remereiments a votre Excellence c'etoit a cause du profond respect, avec le quel je suis

Monseigneur!

de Votre Excellence

à Vienne ce 18 janvier 1758.

le trés humble et trés

obeissant Serviteur JK: Strack

On 21 February 1758, the court informed the cameral directorate that Strack had been employed with an annual salary of 1000 gulden.

The entry in the Protokoll für Hofparteiensachen from February 1758 concerning the employment of Kilian Strack as valet to Archduke Ferdinand (A-Whh, HA OMeA Protokolle 24, fol. 358r).

In 1760, Strack applied for a court quarter ("Hofquartier") in the Sattlerisches Haus in the Kärntnerstraße, which he was granted on 27 November 1760.

The entry in the Hofquartiers-Resolutionen from 1760 concerning the applications for the Hofquartier in the Sattlerisches Haus (AT-OeStA, FHKA AHK HQuA14). The "placet" was written by the Empress.

In 1763, Strack was transferred into the service of the future Emperor Archduke Joseph. As a valet, who also played the cello, Strack regularly played chamber music with the Emperor and, according to an unverified report in the Musikalische Korrespondenz der Teutschen Filarmonischen Gesellschaft (No. 4, 28 July 1790, 27-30), kept music by better composers, such as Haydn, Mozart, Kozeluch, and Pleyel, away from the Emperor.

Strack appears in Mozart's letters for the first time on 16 May 1781, when Mozart, in a postscript, refers his father to Strack as witness for his reasons for staying in Vienna. Mozart calls Strack "my very good friend" which may have been a bit of an exaggeration.

Mozart's postscript in his letter of 16 May 1781 (A-Sm, BD 596). Strack's name is spelled "otrmck" which was Mozart's secret code (s is o, and a is m).

P.S: If you perhaps could believe that I am here only out of hate for Salzburg and out of irrational love for Vienna, – then make enquiries – Herr von otrmck – who is my very good friend, will as an honest man certainly write you the truth. –Deutsch's claim that Mozart made Strack's acquaintance at Hickel's (MBA VI, 66, and Dokumente, 325) is not tenable due to lack of evidence and a skewed chronology. It is true that Hickel made a portrait of Joseph Lange as Hamlet, but this did not happen until 1786, when Joseph II commissioned Hickel to paint portraits of court actors. It seems more likely that it was Strack who introduced Mozart to Hickel.

Based on information from Pisarowitz, in their commentary to Mozart's letter of 16 May 1781, Bauer and Deutsch state that Strack entered imperial service as "widowed soldier", and was married four times (MBA VI, 66). This information cannot be fully corroborated. So far, only three marriages can be documented for Strack, and the evidence for a fourth one is very circumstantial. At he time of his first wedding in 1760, Strack was not widowed, but was expressly described as "L[edigen] St[ands]" (unmarried). Strack's three documented marriages were the following:

1) On 7 June 1760, Strack married Anna Maria Schierl (b. 12 Jan 1719 [St. Ulrich 17, fol. 20v]), daughter of the carpenter Norbert Samuel Schierl (b. 1680, Holedeč, d. 31 Mar 1735, Vienna [St. Ulrich 17, fol. 189r]) and Anna Maria, née Wiltinger. Witnesses: Joseph Carl, majordomo, and Carl Roncke, tutor of young gentlemen (Schotten 31, fol. 49v [this is the wedding Pisarowitz was unable to find]). Maria Anna Strack died of "Innerlicher Brand (internal gangrene) on 2 February 1762, at 8.15 a.m., at Strack's Hofquartier, the "Satlerisches Haus" near the Kärntnertor. This was the same building at the southern end of the Kärntnerstraße where in 1741 Antonio Vivaldi had died.

1) On 7 June 1760, Strack married Anna Maria Schierl (b. 12 Jan 1719 [St. Ulrich 17, fol. 20v]), daughter of the carpenter Norbert Samuel Schierl (b. 1680, Holedeč, d. 31 Mar 1735, Vienna [St. Ulrich 17, fol. 189r]) and Anna Maria, née Wiltinger. Witnesses: Joseph Carl, majordomo, and Carl Roncke, tutor of young gentlemen (Schotten 31, fol. 49v [this is the wedding Pisarowitz was unable to find]). Maria Anna Strack died of "Innerlicher Brand (internal gangrene) on 2 February 1762, at 8.15 a.m., at Strack's Hofquartier, the "Satlerisches Haus" near the Kärntnertor. This was the same building at the southern end of the Kärntnerstraße where in 1741 Antonio Vivaldi had died.

den 2tMaria Anna Strack was buried in the evening of 4 February 1762, in the cemetery around the Cathedral (A-Wd, Bahrleihbuch 1762, fol. 25v, 26r).

Strack (tit[ulo]) Hr: Johann Kilian Kaÿ[serlich] König[licher] / Camer diener, sein Frau Maria Anna / ist beÿn Cärntner thor in Satlerisch[en] / Hauß an Innerl[ichem] Brand besch[aut] word[en] alt 41 J[ahr] früh um 3/4 auf 9 uhr / verschie[den] (M: R:)

Maria Anna Strack, wife of the I. & R. valet Johann Kilian Strack, 41 years of age, was inspected as having died of internal gangrene at the saddler's house near the Carinthian Gate on February 2nd [1762], at 8.15 a.m. Matthäus Rauscher [coroner]

An entry concerning Strack's possible second marriage could not be found. The presumption that between 1762 and 1767 Strack could have married again is probably based on a single document. On 16 January 1767, a Philipp Johann Kilian Strack was baptized in the Cathedral's succursal church in Erdberg, son of "Jo[ann]es Kilianus Strack, ein Camer=diener", and his wife Catharina, with Carl Philipp Peringer, a civil master carpenter, officiating as godfather (A-Wd, Tom. 86, fol. 291v). Since the death of a Catharina Strack does not appear in the municipal Totenbeschauprotokoll between January 1767 and May 1768, this appears to have been an illegitimate child whose baptism Strack hid in Erdberg.

2) On 20 May 1768, Strack married Maria Franziska Aloysia Schandl (1731–1771), chambermaid of Countess Maria Walpurga von Lerchenfeld, née Countess von Trauttmannsdorff, tutor of Archduchess Antonia. The wedding's witnesses were Joseph Carl, majordomo with Prince Dietrichstein, and Johann Thomas Bauer, valet to Archduke Maximilian (Burgpfarre 4, 79).

Johann Kilian Strack's and Maria Francisca Schandl's marriage contract which was signed on 20 May 1768 (A-Whh, HA OMaA 803-419). Contrary to Pisarowitz's assumption, Franziska Schandl was not related to Johann Baptist Gänsbacher's wife Juliana Schandl.

Franziska Strack died on 27 November 1771, at 11 a.m., of "hitziges Gallfieber" (hot gall fever) at the Fernerisches Haus on the Graben.

Because Franziska Strack had been an employee of Countess von Lerchenfeld, her estate was settled by the K.K. Obersthofmarschallamt (the I. & R. supreme Court Marshal's office). Her estate closed with a deficit of 67 gulden 6 kreuzer. The probate file shows that the couple had no children.

Johann Kilian Strack's final calculation concerning the negative net value of his second wife's estate (A-Whh, HA OMaA 803-419)

Franziska Strack was buried on 29 November 1771, in the new crypt under the Cathedral (A-Wd, Bahrleihbuch 1771, fol. 323v and 324r).

3) On 22 June 1775, Strack married Katharina Popp (b. 29 Jun 1746 [A-Wd, Tom. 76, fol. 280v]), daughter of the tailor and servant Benedikt Popp (b. 9. Mar 1708, Greillenstein [Röhrenbach 3, fol. 32v]) and Barbara, widowed Litzgy (A-Wd, Tom. 51, fol. 515r). The bride resided with her mother on the Wieden, Strack's best man was Joseph Konrad Mesmer (1735–1804), head of the school of St. Stephen's (cousin of Franz Anton Mesmer).

The entry concerning Johann Kilian Strack's and Katharina Popp's wedding in 1775 (A-Wd, Tom. 76, fol. 280v)

With his third wife, Strack had the following eight children of whom five survived their father (in honor of the Emperor, all sons bore the attributive name Joseph).

- Joseph Carl, b. 28 Jan 1776, godfather: Joseph Raidegg (1729–1806), I. & R. chamber jeweler (A-Wd, Tom. 92, fol. 263v), d. 12 May 1852 (Schotten 19, fol. 179)

- Joseph, b. 26 May 1777, godfather: Joseph Quarin, doctor of medicine (A-Wd, Tom. 93, fol. 266r), d. after 1865

- Joseph Kilian Ferdinand, b. 6 Sep 1778, godfather: Joseph Quarin (A-Wd, Tom. 95, fol. 2v), d. between 1793 and 1823

- Joseph Jacob, b. 24 Jul 1780, godfather: Joseph Raidegg (A-Wd, Tom.96, fol. 152r), d. before 1793

- Joseph Albin, b. 1 Mar 1782, godfather: Joseph Quarin (A-Wd, Tom. 97, fol. 270r), d. 27 Jul 1782 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 81, S, fol. 66v)

- Maria Anna Catharina, b. 8 Apr 1783, godmother: Maria Anna Weiß (1749–1811), singer at the Burgtheater (A-Wd, Tom. 98, fol. 175v), d. 19 Jan 1851 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 209, S, fol. 5r)

- Catharina Josepha, b. 14 May 1785, godmother: Katharina Pfaller instead of Joseph Quarin (St. Peter, Tom. 1, 91), on 4 Sep 1806 (A-Wstm, Tom. 10, fol. 34) married Dr. Joseph Horniker (b. 1771 in Lemberg, baptized 3 Aug 1805 [St. Peter, Tom. 2, fol. 49], d. 4 Feb 1863), d. 5 Aug 1859 (Wiener Zeitung, 9 Aug 1859, 3383)

- Joseph Franz, b. 3 Oct 1786, godfather: Joseph Quarin (St. Peter, Tom 1, 126), d. 25 May 1790 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 94, S, fol. 73r)

Johann Kilian Strack listed as tenant on the third floor of Stadt 585 in the 1788 Josephinische Steuerfassion (A-Wsa, Steueramt B34.3, fol. 453). On the fifth floor of this house lived the violinist and copyist Jakob Nurscher (see also: Schotten 36, fol. 196).

The fact that Strack's residence was located directly opposite of Mozart's room on the Graben, makes it again very likely that Mozart made Hickel's acquaintance at Strack's and not the other way around. The Wien Museum owns a couple portrait of Strack and his third wife Katharina by an anonymous painter from around 1780. There is no question that these two portraits were painted by Joseph Hickel.

Strack's close relationship with imperial musicians is also documented by his role as best man at Johann Nepomuk Stadler's wedding on 1 June 1783.

The entry concerning Johann Stadler's wedding in the earliest marriage register of St. Josef ob der Laimgrube. Strack's name is at the bottom (Einschreibbuch der Brautleute von der Pfarrei zum H. Joseph ob der Laimgrube für das Jahr 1783 vom 20ten April bis zum letzten Xber 783, 18).

In 1790, after the death of Joseph II, Strack was retired with an annual pension of 1050 gulden. As was usual with every retirement of a court official, a possible successor immediately applied for his position. On 2 December 1791, the Obersthofmeisteramt had to deal with an application from the cellist Joseph Weigl for (among other favors) "Strack's position as chamber violoncellist which has already been vacant for several years."

The Obersthofmeisteramt commented as follows: "As far as his further application for the chamber violoncellist position is concerned, I am not aware that Strack has died, and even less that he received a special salary for this supposed position. If it really did exist, it no longer seems necessary to fill it at this time." (A-Whh, OMeA 357/1792). All Weigl received was a small raise.

On 23 March 1791, Strack signed his will. He bequeathed all the furnishings and household appliances to his wife, and he left his modest assets in equal shares to his wife and five children. The final paragraph of Strack's will reads as follows.

Finally, I recommend my remaining underage children to the well-known tender care of their mother, and to the grace of all her patrons, but especially to the highest protection of His Majesty the Most Gracious Emperor, with the most urgent request of a dying father, to bestow on these helpless orphans, out of ancestral gentleness, at least a small part of the numerous graces and favors that I have always strived to make myself worthy through the 32 years I spent as a valet with Archduke Ferdinand, His Royal Highness, and the late Most Blessed Emperor Joseph, His Majesty, and that I had the inestimable luck to enjoy to the fullest until the end of my life.

The second page of Strack's will with its opened envelope laid over the following empty page (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 831/1793). The first witness was privy councilor Konrad Baron von Nefzern (1739–1814), the second witness was Franz Anton von Sonnenfels, younger brother of the more famous Joseph von Sonnenfels. Baron Nefzern's wife Eleonora von Hay was Joseph von Sonnenfels's sister-in-law.

On 16 January 1793, Johann Kilian Strack died of a stroke. He was survived by his third wife and his children Joseph Karl, Joseph, Kilian Joseph, Catharina, and Catharina Josepha.

The entry concerning the inspection of Johann Strack's body by the municipal coroner on 16 January 1793 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 99, S, fol. 5r)

[den 16ten]v[on] Strack Tit[ulo] H[err] Johann, K:K: Kamerdiener, gebürtig von Mainz in Reich, ist im Fernerischen H[aus] N° 585 im Peternostelgaßl[sic] an widerholten Schlagfluß besch[aut] word[en] alt 68 Jr. Reitter

Mr. Johann von Strack, I. & R. valet, born in Mainz in the German Reich, was inspected at Ferner's house Nr. 585 in the Paternostergassel as having died of repeated strokes, aged 68 years. Reitter [coroner]

Strack was buried on 17 January 1793, in the Matzleinsdorf cemetery (A-Wd, Bahrleihbuch 117, fol. 30v). His probate file shows that his estate was valued at only 388 gulden 42 1/5 kreuzer of which 227 f 26 x were pension arrears (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 831/1793). But that was the gross amount, of which only 354 gulden 28 kreuzer remained after all outstanding bills had been paid. Johann Thorwart was appointed guardian of Strack's children. Johann Kilian Strack's widow Catharina was granted an annual pension of 400 gulden. She died on 31 January 1823 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 153, S, fol. 9r).

On 3 November 1800 (St. Johann Nepomuk 1, fol. 68), Strack's eldest son Joseph Karl married Karl von Marinelli's daughter Josepha (1783–1846) with whom he had four children (and from whom he separated after 1807). Their first son Karl Joseph Franz (b. 31 Mar 1801) became a priest and, as Father Eugen Strack, a Cistercian in Heiligenkreuz Abbey where on 30 March 1864 (Heiligenkreuz 7, 18), he died as the abbey's librarian.

Strack's second son Joseph Strack became one of the most important military historians of the Austrian monarchy. Among other historical studies, he published the standard work Die Generale der österreichischen Armee. Nach k. k. Feldacten und andern gedruckten Quellen (Vienna 1850).

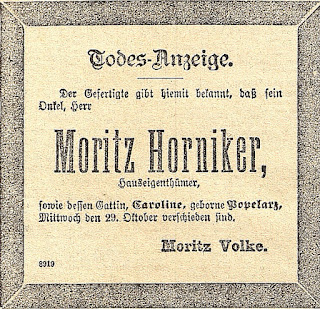

In 1884, Strack's grandson, the retired lawyer and house owner Moritz Horniker (1807–1884), made headlines when he committed suicide. His wife Caroline, née Popelarz (1841–1884), had poisoned herself, and Horniker was so shaken that he shot himself three hours after her death (Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 20 Oct 1884, 4f.). Horniker owned the house Stadt 919 (today Weihburggasse 14). Since the Horniker couple had no children, Horniker's sister-in-law Marquise Ruiz des Roxas and his nephew Moritz Volke were the main heirs.

The death notice of Strack's grandson Moritz Horniker and his wife Caroline (Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 1 November 1884, 26). Horniker's paternal grandfather was Esdras Horniker, a Jewish tailor from Lviv.

Johann Kilian Strack's great-grandson Moritz Volke (b. 21 Sep 1839 [St. Josef ob der Laimgrube 22, fol. 272], grandson of the publisher Friedrich Volke) was curator and librarian at the Technologisches Gewerbemuseum in Vienna. He died on 25 January 1925, in Waidhofen an der Ybbs (Waidhofen, Tom 16, fol. 32). His daughter Margarethe Pauline Adolfine Volke (born 1876) – Strack's last known great-great-granddaughter – died on 16 July 1957, in Waidhofen an der Ybbs. This Lower Austrian town became the residence of the Volke family, because Moritz Volke's father's second wife was Pauline Winkler von Forazest, whose family ran a scythe forge in Waidhofen.

Joseph Hickel

Joseph Hickel was born on 19 March 1736, in Böhmisch-Leipa (Česká Lípa) (Schöny 1970, 91), son of the painter Johann Hickel (1705–1778) and his wife Anna Eleonora, née Melzer. Joseph learned from his father. In 1756, he entered the Vienna Academy, where he said he worked for ten years. In 1768, he went to Italy on behalf of Empress Maria Theresa to paint numerous portraits of prominent personalities in Milan, Parma and Florence. In 1770, he was back in Vienna. In 1772, he was appointed adjunct to the imperial picture gallery with an annual salary of 700 gulden, and in 1776, appointed I. & R. chamber painter. In the same year, the Vienna Academy accepted him among its members and also exhibited several of his works.

Joseph Hickel's 1769 self-portrait (Firenze, Galleria degli Uffizi, Inventari 2062/1890). There exists also a clumsy engraving of this portrait (A-Wn, PORT_00027154_01).

It cannot be denied that Hickel's work was limited to rather monotonous portraiture and that he can be accused of having strived for mass production. It is said that he made around 3000 portraits in his lifetime. Because of this limitation to one subject, his artistic significance must be considered minor. The Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (Leipzig: Verlag von Duncker & Humblot, 1880) described his work as follows: "Given his rapid productivity, not all his paintings are of significant artistic value. But some of them show impeccable understanding, great intellectual expression, and eloquent resemblance of the people portrayed." It must be noted (and the above portraits of the Strack couple show this exemplarily) that the quality of Hickel's work also depended on the social status of the person portrayed. Because of his portraits of members of the imperial family and the nobility, Hickel became Joseph II's favorite portrait painter.

The emperor's preference may have had to do with the fact that Hickel's style was rather conservative and was based heavily on painters of the previous generation, such as Martin van Meytens.

When in 1782 Hickel tried to succeed the incapacitated Caspar Sambach as director of the I. & R. painting academy, and presented an extensive, but slightly illusory reform program to the Emperor, he encountered determined resistance from the academy's protector Prince Wenzel Anton von Kaunitz-Rietberg, who, on 21 December 1782, in a letter to Baron Joseph von Sperges, wrote the following about Hickel's application:

On 14 May 1770, in Vienna, Joseph Hickel married Margaritha Wutka, born on 14 January 1753, in Vienna (A-Ws, 34, fol. 11v), daughter of Engelbert Wutka (b. 5 Nov 1714, in Hodonín [Moravském zemském archivu v Brně, Hodonín 5303, 397]), secretary of Prince Emanuel von Liechtenstein, controller of the I. & R. gunpowder and saltpeter administration, and administrator of the I. & R. armory. When Engelbert Wutka had married for the first time on 10 August 1750, in Valtice (A-Wstm, 6, 538), his best man had been Philipp Schäffer, counselor of Prince Liechtenstein and none other than Baroness Waldstätten's father. At the time of her wedding in 1770, Margaritha Wutka was already an orphan. Her mother had died on 2 June 1760 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 54, W, fol. 13r), her father (who had married again in 1761 [A-Wd, 60, fol. 162v]) had died on 16 June 1769 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 63, W, fol. 16v).

Joseph Hickel's best man was Leopold Pölt, registrar with the I. & R. Bohemian and Austrian court chancellery, the bride's witness was her guardian, the artillery expeditor Joseph Ziegler. The couple's marriage contract was signed on 9 May 1770. The bride brought a dowry of 500 gulden into the marriage to which the groom responded with 1000 gulden.

The couple had no children, but Margaritha Hickel adopted a five-year-old girl named Karoline Lambert (born 1 Oct 1802 [Maria Treu 7, 398]), who in 1831 was a chambermaid to Archduke Charles (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 1195/1831) and was still alive in 1858 (Liste der Badner-Curgäste, Nr. 57, 1858). Between 1782 and 1805, Joseph and Margharita Hickel are documented to have lived at Stadt No. 343, a house between the Salzgries and the armory. Since Theresia Wutka lived in her brother-in-law's household, this was the house where the serenade K. 375, written for Theresia, was premiered on 15 October 1781.

Daily experience alone can show how much self-love can blind people. This wretched man [Hickel], who cannot draw and is only able to paint a head very mediocrely at most, thinks he is a worthy director of the painting academy and, through his guidance alone, can educate artists from the large crowd of scribblers who will be able to exhibit for sale so much good stuff every six months that from this a rich fund will be drawn for their and the sustenance of others, without thinking of all the other absurd ideas with which his presentation to the Emperor is filled. In order to prevent all adverse impressions that such a person may make, regardless of this, your Honor may wish to draft a lecture on such matters, in which every absurdum must be cited and refuted point by point. And as far as the requested appointment as director-adjunct is concerned, the Emperor will have to be informed that this good man is the weakest person who could be chosen for this purpose. (Raab 1879, 1 [my translation])In his report to the Emperor, Baron Sperges added the following: "Not only ingenuity, correct drawing, good color, understanding in composing, and what makes a good painter, but also a thorough insight into art in general, the ability to judge, knowledge of mythology and history, no less of older and more recent art history, foreign languages, modesty and good manners in teaching are necessary for a director of the painting school, if he is to have the confidence of his students, gain respect from art connoisseurs and preside over the office with honor – all qualities that Hickel lacks." The post of director of the Vienna academy was eventually given to Heinrich Füger.

On 14 May 1770, in Vienna, Joseph Hickel married Margaritha Wutka, born on 14 January 1753, in Vienna (A-Ws, 34, fol. 11v), daughter of Engelbert Wutka (b. 5 Nov 1714, in Hodonín [Moravském zemském archivu v Brně, Hodonín 5303, 397]), secretary of Prince Emanuel von Liechtenstein, controller of the I. & R. gunpowder and saltpeter administration, and administrator of the I. & R. armory. When Engelbert Wutka had married for the first time on 10 August 1750, in Valtice (A-Wstm, 6, 538), his best man had been Philipp Schäffer, counselor of Prince Liechtenstein and none other than Baroness Waldstätten's father. At the time of her wedding in 1770, Margaritha Wutka was already an orphan. Her mother had died on 2 June 1760 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 54, W, fol. 13r), her father (who had married again in 1761 [A-Wd, 60, fol. 162v]) had died on 16 June 1769 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 63, W, fol. 16v).

The entry concerning Joseph Hickel's wedding on 14 May 1770 (A-Wd, Tom. 65, fol. 186v). The banns for Hickl's wedding were published on 1 May 1770 at the Schotten parish, because Hickel lived at the armory on the Renngasse, Engelbert Wutka's former workplace (Schotten, Tom. 33, fol. 31r).

Joseph Hickel's best man was Leopold Pölt, registrar with the I. & R. Bohemian and Austrian court chancellery, the bride's witness was her guardian, the artillery expeditor Joseph Ziegler. The couple's marriage contract was signed on 9 May 1770. The bride brought a dowry of 500 gulden into the marriage to which the groom responded with 1000 gulden.

The third page of Joseph Hickel's and Margaritha Wutka's marriage contract (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 2441/1807). The groom's witness was the registrant at the I. & R. Bohemian and Austrian court chancellery Leopold Pölt (1736–1814), who in 1800 was appointed court secretary, and in 1810 was ennobled with the predicate Pölt von Pöltenberg. He was the grandfather of the revolutionary general Ernst Pölt von Pöltenberg who was executed in 1849. The bride's witness was the I. & R. General Artillery Weapons Office Chancellor Carl Joseph Ziegler, a colleague of the bride's father.

The couple had no children, but Margaritha Hickel adopted a five-year-old girl named Karoline Lambert (born 1 Oct 1802 [Maria Treu 7, 398]), who in 1831 was a chambermaid to Archduke Charles (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 1195/1831) and was still alive in 1858 (Liste der Badner-Curgäste, Nr. 57, 1858). Between 1782 and 1805, Joseph and Margharita Hickel are documented to have lived at Stadt No. 343, a house between the Salzgries and the armory. Since Theresia Wutka lived in her brother-in-law's household, this was the house where the serenade K. 375, written for Theresia, was premiered on 15 October 1781.

The house Stadt 343 between the Salzgries and the armory on Huber's 1778 map of Vienna (W-Waw, Sammlung Woldan). At this house (last number 186) the writer Joseph Schreyvogel and his son-in-law Joseph Beckers died on 28 and 29 July 1832. The tenant after Schreyvogel in apartment number 7 of this house was Leopold Kupelwieser (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Stadt 186/23r).

In 1788, Hickel was registered in the Steuerfassion as tenant of "six rooms, kitchen, a firewood vault, and attic" on the fourth floor of this house for an annual rent of 360 gulden.

Joseph Hickel registered in 1788 as tenant at the house Stadt 343 (A-Wsa, Steueramt B34/2, fol. 7)

Hickel's address "sur le Salzgries N° 343 au troisieme etage" is also documented on Johann Jacobe's engraving of Hickel's portrait of Pope Pius VI (Wien Museum, I.N. W 5236). The original portrait of the Pope has been lost (Thomasberger 1989, 44).

Hickel's address on Jacobe's engraving of his portrait of Pope Pius VI (Wien Museum I.N. W 5236)

In 1786, Joseph II commissioned Joseph Hickel to paint a series of portraits of court actors that were to be hung in the corridor from the Hofburg to the Burgtheater. This Ehrengallerie of famous actors was one of the first of its kind in Europe. The work on this gallery must have taken a few years, because Hickel's brother Anton, who was called in to help, was only in Vienna between 1789 and around 1791, when he came from Paris and had a trip to England in mind. Two of these portraits of actors were painted posthumously, such as those of Gottfried Prehauser (A-Wkm, Theatermuseum GS_GPS565) and Conrad Steigentesch (A-Wkm, Theatermuseum GS_GPS599). Some of the paintings were enlarged at the bottom in 1888, when the Burgtheater moved into the new venue (Thomasberger 1989, 52-54).

Joseph Hickel's portrait of Joseph Lange as Hamlet (in the moment he sees his father's ghost) in its original size (Wien Museum 2012)

Joseph Hickel's portrait of Joseph Weidmann in the role of Johann in Friedrich Wilhelm Gotter's comedy Der Kobold (Wien Museum 2012)

Joseph Hickel's portrait of Johanna Sacco in the title role of Gotter's melodrama Medea. According to Meusel, this portrait was already painted in 1784 by Anton Hickel (Meusel 1785, 316).

On 16 October 1784, for 1800 gulden, Hickel bought the house Erdberg No. 290, "Zur Weintraube", in the Rittergasse (today Erdbergstraße 33), from the innkeeper Johann Georg Pischinger and his wife. When in 1785 it turned out that the house's "Greißlergerechtigkeit" (grocer's license) had not been fully registered, Hickel went to court and had the purchase reversed. (A-Wsa, Patrimonialherrschaften, 102.A3.3, 3429). When Pischinger was unable to repay the purchase price, Hickel asked the court to put the house up for sale at an inflated price and was able to finally purchase it far below this price in January 1786 (Wiener Zeitung, 18 January 1786, 134). In 1807, this house was valued at 5500 gulden.

The house Erdberg 290 that Hickel bought in 1784 (Wien Museum I.N. 27018/1). This building was torn down in the early 20th century.

In 1803, Hickel also bought the much smaller, neighboring single-story house (then Erdberg No. 341, today Erdbergstraße 31). In 1807, this house was valued at 1200 gulden.

The first page of the entry concerning Joseph

Hickel's house Erdberg 290 in the 1788 Steuerfassion (A-Wsa, Steueramt, B34.8, fol. 312). The annual total rental yield of this house in 1788 was 500 gulden.

Hickel lived in the house at Stadt 186 until shortly before 1807, when he moved to Hoher Markt No. 480 (last number 446, today in front of Marc-Aurel-Straße 1), where he eventually died. Since the conscription sheets of Stadt 446 are only preserved as of 1821, there is no sheet for this house on which Hickel is listed.

Joseph

Hickel and his wife registered in 1805 on the earliest surviving conscription sheet of Stadt 186 (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Stadt 186/1r)

On 25 November 1800, Hickel wrote his will. He left the two children of his deceased sister Eleonora Hucker 1000 gulden, his brother Karl 1000 gulden, his brother Johann 3000 gulden, and his sister Franziska 1000 gulden, which were to be invested for her children and from which she was only to draw the interest rates. His nephew Joseph Meltzer was to receive 500 gulden. He confirmed his marriage contract from 1770 in all paragraphs, appointed his wife universal heir, and allowed her to give each of his three siblings "one or the other painting from his collection" as a souvenir.

The last two pages of Joseph Hickel's autograph will written on 25 November 1800 (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A10, 209/1807)

Joseph Hickel died on 28 March 1807, of "Gedärmbrand" (intestinal gangrene)

The entry in the death register concerning the inspection of Joseph Hickel's body by the municipal coroner on 28 March 1807 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 122, H, fol. 24r)

Hickel died a wealthy man. It was not the two houses that made up his fortune, but rather the bank bonds worth over 13,000 gulden in which he had invested the profits from his artistic work. In addition, there was half the value of his two houses and his garden in Erdberg, which was estimated at 4,209 gulden. Together with his jewelry (650 fl), clothing and household appliances (457 fl), and the collection of paintings (335 fl), his net assets totaled 19,522 gulden and 27,5 kreuzer.Den 28tenHickel Herr Joseph k.k. Cabinets-Mahler, verheurath, von Laipa aus Deutschböhmen gebürtig, ist im Riederischenhaus N° 480 am Hohenmarkte am Gedärmbrand beschaut worden, alt 72 Jr. Pierner

On 13 April 1807, Hickel's widow declared herself universal heir to the Vienna Magistrate.

Margaritha Hickel's declaration as universal heir (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A10, 209/1807)

In 1811, she signed a declaration that, in accordance with her husband's wishes, in the event of her death, she would leave half of his estate to his three siblings and his sister's son Gottfried Hucker, in four equal parts. And in the event that one of these relatives should die before her, she promised to pass on the share to the others or their descendants.

In his article about Joseph Hickel (BLKÖ 9, 4), Constant von Wurzbach quotes an anonymous obituary which described Hickel's character as follows: "As a person, Hickel was a real artist, cheerful in his dealings, kind to the poor, honest in his way of thinking, open and unreserved in his judgments."

Theresia Wutka

Maria Theresia Josepha Catharina Cajetana Wutka, the dedicatee of Mozart's K. 375, was born on 29 August 1756, in Vienna, daughter of Engelbert Franz Wutka and his wife Catharina (Schotten, Tom.34 fol. 304r). Her godmother was Margaretha Kempf de Angret who was represented by Theresia von Lauch, née Pentzeneder von Pentzenstein.

The entry concerning Theresia Wutka's baptism on 29 August 1756 at Vienna's Schottenkirche (A-Ws, Tom.34 fol. 304r). The research into the genealogy of Theresia and Margherita Wutka's godmother Margaritha Kempf de Angret leads into interesting cultural areas and, in an interesting way, leads back to the Mozart circle. Margeritha von Serdagna (also Sardagna) was born in 1710, daughter of the court physician Nicolaus von Serdagna and Elisabeth, née de Battaille. The Serdagna family came from Cassá de la Selva in the province of Gerona and probably moved to Vienna in 1712, with Emperor Charles VI. The presence of Nicolaus von Serdagna (1672–1757) in Vienna is documented for the first time in 1717, on the occasion of a purchase of land for the construction of the new Spanish Hospital. Margeritha von Serdagna's brother, Nicolaus Salvator von Serdagna (1702–1758) was also a physician in Vienna. On 27 April 1740, Margherita von Serdagna married the Imperial Obrist-Land- und Hauß-Zeugamts-Secretarius Bernhard Dismas Kempf de Angreth (1696–1765) (Hofburg 1, 640), who came from Alsatian nobility and in 1759, was elevated to the status of baron together with his brother (AT-OeStA/AVA Adel HAA AR 435.2). Margherita Kempf de Angret died childless on 25 March 1787 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 88, CK, fol. 22v). She bequeathed the dominion of Leopoldsdorf im Marchfeld, which she had inherited from her husband, to her nephew (son of Nicolaus von Serdagna the Younger) Raymund von Sardagna (1749–1819). And here we return to Mozart's environment: on 28 February 1779 (A-Wd, 95, fol. 122v), Raymund von Serdagna acted as godfather to Raymund Wetzlar von Plankenstern, Mozart's friend and godfather to Mozart's first son Raymund Leopold. On 26 March 1777, Margaritha Kempf de Angret officiated as godmother of Margaritha Mitscha (A-Wd, Tom. 93, fol. 223r), daughter of the state official and composer Adam Mitscha, and niece of Mozart's future pupil Josepha Auernhammer. And finally, on 2 July 1799, Raymund von Serdagna's son Joseph married Franziska von Thorwart, only daughter of Constanze Weber's guardian Johann von Thorwart (AT-OeStA/KA, MMatr, Feldsuperiorat, fol. 36). On 31 October 1798, Raymund von Sardagna was also best man at the wedding of Franz Karl Neilreich and Josepha von Kurzböck, the future parents of the botanist August Neilreich (A-Wd, 79, fol. 228).

Some authors have associated Theresia Wutka with Joseph Hickel's younger brother Anton who was baptized on 31 March 1745, in Böhmisch Leipa.

The entry concerning the baptism of Johann Anton Hickel on 31 March 1745, in Böhmisch Leipa (Státní oblastní archiv v Litoměřicích, Böhmisch Leipa, Taufen 1743-1757, 68). In 1885, after Emperor Franz Joseph I had presented a painting by Anton Hickel to the National Portrait Gallery in London, British authors came up with the name "Karl Anton Hickel" (The Antiquary 1885, 130), which immediately began to soak into the literature. This false name now appears in various art encyclopedias.

In his genealogical study Wiener Künstler-Ahnen, Heinz Schöny in 1970 presented the idea that Theresia Wutka may have been married to her brother-in-law Anton Hickel. This information is presented as fact in the commentary of MBA with Pisarowitz being given as source (MBA VI, 91).

Heinz Schöny's assumed marriage of Anton Hickel and Theresia Wutka in his genealogy of the Hickel brothers (Schöny 1970, 91). It is no longer possible to determine if Schöny or Pisarowitz published this information first.

Schöny's presumption is false. Theresia Wutka was not married to Anton Hickel. As a matter of fact, she never married at all. With the help of conscription sheets and extensive genealogical research, Theresia Wutka's activities and her social environment during the second half of her life can be explored. Three Viennese families formed Wutka's social framework during this time: the von Eberl family, the Marx family, and the Sicard family.

Between 1805 and 1810, we find Theresia Wutka as governess of the sisters Theresia, Rosalia, and Antonia von Eberl. They were three orphaned daughters who in 1804 had moved from Stockerau to Vienna after the death of their father, the postmaster Johann Michael von Eberl (1759–1804) (Stockerau 11, fol. 15). Wutka appears together with the three girls on a conscription sheet of Stadt 635 ("Zur Silbernen Kugel", today Rotenturmstraße 7). She was employed there by the Hofkammer-Ratsprotokollist Leopold Strasser (b. 16 Nov 1763) who was the second husband of Carolina von Eberl, née Marx (1750–1825), widow of the three girls' uncle, Carl Joseph Anton von Eberl (1752–1797).

Around 1815, Theresia Wutka lived at Stadt 668, the so-called Dominikaner-Zinshaus (today Predigergasse 1), where she was registered as "Pensionistin" (retiree). At that time, she was living in the household of the k.k. Kassaofficier Franz Grebeschütz (1783–1834), who, on 10 October 1810 (A-Wd, Tom. 82b, fol. 293), had married Theresia von Eberl (1790–1815), the eldest of Wutka's abovementioned three fosterlings. Rosalia and Antonia von Eberl also lived in this apartment.

Theresia Wutka registered together with Franz Grebeschütz's family on a conscription sheet of Stadt 668 (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Stadt 668/1r). Theresia Grebeschütz, née von Eberl died on 3 December 1815 (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 3060/1816). Franz Grebeschütz's second wedding took place on 11 January 1819 (Schotten, Tom. 42, fol. 188).

Shortly after 1818, Theresia Wutka was registered by the municipal conscription office as living at Stadt 719 ("Zu den zwei goldenen Schlüsseln", today Franz-Josefs-Kai 15).

Theresia Wutka registered after 1818, on a conscription sheet of Stadt 719 (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Stadt 719/9r).

Theresia Wutka spent the last years of her life in the company of the court secretary's widow Anna Baumgartner on the third floor of Stadt 583 ("Zum Blauen Herrgott", today Bauernmarkt 14) This address is first documented in the probate file of Margeritha Hickel (who died on on 11 February 1831) where her sister is given as "eine leibl: Schwester Theresia Wutka ledig in der Stadt am Bauernmarkt zum blauen Herrgott".

Theresia Wutka and Anna Baumgartner's shared apartment is noted in Wutka's probate file which states: "Wohnung Stadt Nr. 538(sic!) Taschnergasse bey Frau Anna Baumgartner K.K. Hofsekretärs Witwe." Accordingly, Wutka and Baumgartner appear together on a conscription sheet of Stadt 583.

Theresia Wutka and Anna Baumgartner (misspelled "Baumgarten") registered in the 1830s, on a conscription sheet of the house Stadt 583 (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Stadt 583/18r)

Theresia Wutka died on 29 December 1841, at the hospital of the Sisters of Mercy at Gumpendorf 195 (today Gumpendorfer Straße 108) where Anna Baumgartner had placed her for care. Two days later, she was buried in the Hundsturm cemetery (Gumpendorf, Tom. 18, fol. 69).

The entry in the death register concerning the inspection of Theresia

Wutka's body on 29 December 1841 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 189, W, fol. 50r)

Wutka Theresia, K:K: Pulver= u Salpeter=Cassa=Liquidators = hinterlassene Tochter, kath: 85 J: a: von Nro an AltersschwächeThe information in Theresia Wutka's four-page probate file, drawn up by the Sperrskommissär Laurenz Kromar, can be summarized as follows. Since Wutka had died at the hospital of the Sisters of Mercy in Gumpendorf (an institution that still exists today), and the nuns had only been given Wutka's essential personal data, her home address was unknown. Therefore, the following information was first entered into the file: "Stadt 538, Taschnergasse at a certain Baumgartner's, but further details are unknown and there is no document available."

dt: dt: [bei den barmherzigen Schwestern]

Wutka Theresia, left behind daughter of an I. & R. powder and saltpeter cashier administrator, catholic, 85 years of age, from Nro, [died] of old age

same same [at the Sisters of Mercy]

The outside of the cover sheet of Theresia Wutka's Sperrs-Relation (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 1033/1842)

Concerning Wutka's personal belongings, the following was noted: "In the Hospital of the Sisters of Mercy: Nothing, and there is no claim outstanding there either. Incidentally, the exact location of the place of residence of the deceased is also unknown there." The local authorities had to request the assistance the I. & R. police headquarters to find out the home address of the deceased, and her landlady Anna Baumgartner. It took the civil court until February 1842 to add the following note: "About the information received from the police department that Mrs. Anna Baumgartner lives in the city No. 338 on the 3nd floor and Theresia Wutka had been staying with her".

The inside of the cover sheet of the same document (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 1033/1842)

Only in March 1842 Anna Baumgartner came forward and presented a deed of gift, dated 4 December 1838, in which Theresia Wutka had "assigned and handed over all of her possessions to Anna Baumgartner as an inter vivos gift as her full irrevocable property." Since Wutkas's deed of gift, which Anna Baumgartner had to personally submit to the civil court in April 1842, was not officially registered as a will, it is not preserved.

Theresia Wutka's last friend Anna Baumgartner

Anna Baumgartner was born Anna Lautter, on 18 November 1770 (A-Wd, Tom. 89, fol. 89r), daughter of Johann Michael Lautter (1733–1784) and his second wife Theresia, née Jahn (1749–1829). Anna's father Michael Lautter (born 29 Sep 1733 [Schotten, Tom. 31, fol. 63v]) had started out as a tailor, but he was so successful in his profession that in 1784, he died a municipal Mobilien-Schätzmeister (appraiser of movables) and owner of the house Stadt 274 (last number 344, Judenplatz 9) (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 3839/1784). On 22 April 1785, Lautter's widow married the Hofkriegs-Cancellist Dominik Sicard (Am Hof 1, fol. 25), whereby Anna Lautter became the half-sister of Dominik Sicard (the architect August Sicard von Sicardsburg's future father). Through this marriage, the house on the Judenplatz came into the possession of the Sicard family and became the basis of this family's real estate assets. Subsequently – after the marriage of Dominik Sicard and Barbara Janschky – it developed into the headquarter of Joseph Janschky's carriage and transport business. Dominik Sicard and Barbara Janschky married on 26 September 1811 (Am Hof, Tom. 3, fol. 139).

The last page of the marriage contract of Dominik Sicard and Joseph Janschky's daughter Barbara, with the signatures of Anna Baumgartner's first husband Franz Marx, her mother Theresia Sicard, and Joseph Janschky senior (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A10, 41/1820). In 1844, there was a second family connection between the Sicard and Janschky families when the architect August Sicard von Sicardsburg married his cousin Aloysia Janschky (Am Hof, Tom. 5, fol. 130).

The various families and social groups intertwined on the occasion of the marriage of Anna Lautter to Franz Marx on 15 October 1792 (Am Hof, Tom. 1, fol. 122). Franz Marx (b. 19 Dec 1751 [A-Wd, Tom. 79, fol. 196r]), who was a "k.k. Feld- und Garnisons-Artillerie-Zeugamtskanzlist" and thus probably an acquaintance of Theresia Wutka's father, was the social link between the Sicard and the von Eberl families. He was the brother of Carolina von Eberl, née Marx, stepmother of the abovementioned von Eberl sisters whose governess was Theresia Wutka. Anna Lautter's witness at this wedding was Leopold Sicard, cousin of her stepfather and guardian Dominik Sicard.

The last two pages of the marriage contract of Franz Marx and Anna Maria Lautter dated 26 July 1792. The bride brought an inheritance of 17,000 gulden into the marriage, the groom only 576 gulden (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A3, 488/1792).

Franz Marx died on 26 July 1819 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt, 145, M, fol. 25v). On 20 August 1821 (Maria Rotunda, Tom. 4, fol. 8), the 51-year-old widow Anna Marx, née Lautter, married the 61-year-old k.k. Hofkriegssekretär Johann Michael Baumgartner (b. 11 Jul 1760 [A-Wd, 84, fol. 106v]). At that time, Theresia Wutka was probably already living in the Baumgartner household. Michael Baumgartner died of consumption on 19 October 1828, aged 68 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 162, B, fol. 90v).

Anna Baumgartner's signature in the Sperrs-Relation of her second husband Michael Baumgartner. The seal is that of the deceased husband (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 5663/1828). For Michael Baumgartner's will see: A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A10, 515/1828.

Anna Baumgartner died of old age on 22 April 1848 (A-Wsa,Totenbeschreibamt 202, BP, fol. 16v). Her probate file lists her closest relatives as follows: "Two half-brothers from the 2nd marriage of the mother of the deceased, namely Mr. Dominik Sicard von Sicardsburg, adjunct at the National Bank, at Stadt 344, and Mr. Johann Sicard von Sicardsburg, captain in the Hartschier life guard, in the guard's house, both of them of age". Anna Baumgartner's universal heir was Johann Sicard von Sicardsburg.

The inside of the cover sheet of Anna

Baumgartner's probate file (A-Wsa, Mag.

ZG, A2, 617/1848). The handwriting is that of the Sperrskommissär Anton Slabe (1787–1860).

Epilogue

Mozart's Serenade K. 375 is a special case in his early chamber music. Its origin connects several social spheres that are not combined again in this way in the case of other pieces. It can be considered certain that Mozart's plan to get to the Emperor through Hickel and Strack never succeeded. One is tempted to assume that he invented the whole plan for his father to fake sophisticated networking and his integration in influential circles.

The above essay is based on decades of archival research. Such a combination of topographical and biographical research, taking into account all existing historical sources, was not possible in the past, when Karl Maria Pisarowitz never went to Vienna and Joseph Heinz Eibl integrated Pisarowitz's incomplete information like a gospel into the published commentary of Mozart's letters. Mozart's Viennese apartments have also never been researched in the way that the existing sources would allow. A fundamental scholarly study about Mozart's apartments will probably never be written, because there is no funding available for such a project in Vienna. Thus, the only option left is to shallowly delve into the research that has so far been neglected in individual meticulous studies like the above, and to hope that some day, similarly detail-loving minds will complete this Herculean task.

Bibliography

Anonymous. 1885. "The Antiquary's Note=Book", in: The Antiquary A Magazine Devoted to the Study of the Past, vol. XII, July–December, London: Elliot Stock.

Bauer, Wilhelm A, Otto Erich Deutsch, and Joseph Heinz Eibl, eds. 1962–1975. Mozart. Briefe und Aufzeichnungen. Gestamtausgabe, 7 vols. Kassel: Bärenreiter.

Braunbehrens, Volkmar. 1988. Mozart in Wien, Serie Musik, Band 8233, München/Mainz: Piper-Schott.

Brauneis, Walther. 1991. "Mozart in Wien". In: Mozart. Bilder und Klänge, 6. Salzburger Landesausstellung, Schloß Kleßheim, Salzburg. 23. März bis 3. November 1991. Salzburg: Salzburger Landesausstellungen, 324ff.

Deutsch, Otto Erich. 1961. Mozart. Die Dokumente seines Lebens. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke, Serie X, Werkgruppe 34. Kassel: Bärenreiter.

Fischer, Joseph Maximilian. 1786. Verzeichniß der in der Kaiserl. Königl. Haupt- und Residenzstadt Wien, sammt dazu gehörigen Vorstädten und Gründen, befindlichen numerirten Häusern, derselben wahrhafte Eigenthümer, und deren Konditionen, nebst Schildern und Plätzen. Vienna: Joseph Gerold.

Meusel, Johann Georg. 1785. Miscellaneen artistischen Innhalts, vol. 5, Erfurt: Keyser.

Pisarowitz, Karl Maria. 1960. "Der k. k. Kammerdiener Strack", in: Mitteilungen der Internationalen Stiftung Mozarteum, Jg. 9, vol. 1-2, 5f.

Raab, Fritz. 1879. "Fürst Kaunitz und Füger", Neue Freie Presse, 28 February 1879, 1f.

Schöny, Heinz. 1970. Wiener Künstler-Ahnen. Genealogische Daten und Ahnenlisten Wiener Maler, 1. Mittelalter bis Romantik, Vienna: Selbstverlag d. Heraldisch-Genealogische Gesellschaft "Adler".

Spiel, Hilde. 1978. Fanny von Arnstein oder Die Emanzipation, Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag.

Thomasberger, Edith. 1989. Joseph und Anton Hickel. Zwei josephinische Hofmaler, PhD, University of Vienna.

Wien Museum Hermesvilla. 2012. Burg Stars 200 Jahre Theaterkult, Vienna: Christian Brandstätter Verlag.

Wolff, Christoph. 2012. Mozart at the Gateway to his Fortune, New York, London: Norton & Company.

For expert help concerning the holdings of the MA 236 I extend my thanks to Hannes Tauber. I am also grateful to Anne-Louise Luccarini and David J. Buch for financial support.

© Dr. Michael Lorenz 2023. All rights reserved.

Updated: 12 August 2025 © Dr. Michael Lorenz 2023. All rights reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

An outstanding piece of work

ReplyDeleteWonderful -- thanks so much for this painstaking research. Is there more new material to be had on the move to the octet version, I wonder?

ReplyDeleteI am also appreciative of the extensive research. I have been looking for information on Joseph and Anton Hickel since 2008. Hopefully your information will lead me to correct Church registers and bio family from 18th Century Bohmisch Leipa. My Hickels were from the Moravska Trebova region and are probably unconnected?

DeleteThank you for the extremely detailed article. Is it certain that the 1888 building is the same one Mozart lived in? The 1888 plan looks so different from the plan of house 1175 on Daniel Huber’s 1778 “Vogelschau der Stadt Wien samt ihren Vorstädten,” which shows a square building with a square courtyard in the middle. The only commonality I can see is that both the 1888 structure and the house on Daniel Huber‘s plan have six windows across. Perhaps I am not reading the 1888 plan correctly.

ReplyDeleteHuber's plan is not usable as an exact topographical source because it simplifies the floor plans. You shouldn't look at Huber, but rather at the Franziszeischer Kataster from 1829. The files in the municipal Unterkammeramt are also very clear.

DeleteThank you for this information. I have been searching for biographical information on Joseph and Anton Hickel since 2008. Hopefully your information will lead me to the correct Church birth records and bio family in Ceska Lipa/Bohmisch Leipa. If you know of a specific church there, I would appreciate it. My Hickel family was from Moravska Trebova region and is probably unconnected?

ReplyDelete