Vittoria Tesi

The alto Vittoria Tesi Tramontini was one of the eighteenth century's great opera singers. Born on 13 February 1701, in Florence, she studied singing in her hometown with the renowned singer Francesco Redi and in Bologna with Francesco Campeggi.

The entry in the records of the Florence Cathedral concerning the baptism of Vittoria Tesi on 15 February 1701 (Firenze, Opera di S. Maria del Fiore, Archivio delle fedi di battesimo di S. Giovanni, Registro 295, Carta 84v). Tesi was born on 13 February and baptized on "Febbraro Martedi [Tuesday] 15" [1701]. Her godmother and namesake was the soprano Vittoria Tarquini.

As early as 1716, she appeared at Parma's Teatro Ducale as Fileno in d'Astorga's Dafni, together with Angiola Algieri and the young Cuzzoni (who sang Galatea in that production). In 1719, she sang in Lotti's Melodramma pastorale Giove in Argo at the newly opened Dresden Opera where she often appeared under Hasse and much contributed to the rapid flowering of the Dresden opera culture. In 1725, in Naples, together with Farinelli, she premiered Hasse's serenata Marc'Antonio e Cleopatra. She made guest appearances in Spain (also with Farinelli) and Italy – for example in the title role of Sarro's Achille in Sciro at the opening of the Teatro San Carlo in 1737 – and from 1741 until 1745, sang at the Teatro San Giovanni Grisostomo in Venice where on 21 November 1744, she created the title role in Gluck's second Venetian opera Ipermestra. In 1747, she moved to Vienna where on 14 May 1748, appearing in the title role, she greatly contributed to the success of the opera Semiramide riconosciuta which Gluck had written for the opening of the rebuilt Burgtheater. In Vienna Tesi also performed in Hasse's Leucippo, Jommelli's Achille in Sciro, and Didone abbandonata. Her last appearances at the Burgtheater took place in 1750. In 1754, at the festivities at Prince Joseph of Saxe-Hildburghausen's palace Schloss Hof, she sang the role of Lisinga in a private performance of Gluck's Le cinesi and also performed in Bonno's Il vero omaggio.

Vittoria Tesi-Tramontini. Portrait of unknown origin from Moriz Bermann's book Maria Theresia und Kaiser Josef II. in ihrem Leben und Wirken (Vienna: A. Hartleben's Verlag, 1881)

After the end of her active career, Tesi became a highly esteemed singing teacher. Among her pupils were Caterina Gabrielli, Anna-Lucia de Amicis, and Elisabeth Teyber. Tesi was one of the great singers of the eighteenth century. In his classic book Pensieri, e riflessioni pratiche sopra il canto figurato (Vienna: von Ghelen, 1774) the castrato and voice teacher Giovanni Battista Mancini describes her as the leading female singer of her era, even putting her above Faustina Bordoni and Francesca Cuzzoni. According to Mancini, Tesi possessed "An excellent and fine complexion, accompanied by a noble and graceful posture, clear and exquisit pronunciation, a vibrato of the words according to their true meaning, the skill to distinguish one role from the other and all different characters with a change of face and the appropriate gesture. Mastery of the stage, and finally, perfect intonation."

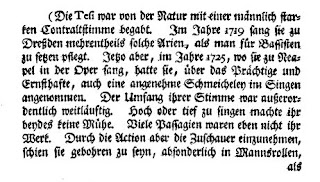

The paragraph in Mancini's Pensieri, dealing with Tesi Tramontini's life and singing voice. Pietro Buzzi's 1912 translation of this paragraph can be accessed here).

In his treatise Anweisung zum musikalisch=zierlichen Gesange (Leipzig: Johann Friedrich Junius, 1780), Johann Adam Hiller quotes the paragraph from Mancini and ads the following information concerning Tesi's singing voice:

Tesi was endowed by nature with a strong, masculine contralto voice. Several times in Dresden in the year 1719, she sang arias which are generally set for basses. Now, however, in the year 1725, while she was singing in the opera house in Naples, she acquired a pleasing and flattering style in addition to her splendid and serious singing. The range of her voice was extraordinarily large. Singing either high or low caused her no trouble. It was not her habit to make use of many passaggi. She seemed to be born to captivate her audience by acting especially in male roles, which she performed to her own advantage in a most natural manner. (translation from Suzanne J. Beicken: Treatise on Vocal Performance and Ornamentation by Johann Adam Hiller. Cambridge University Press 2004, 44f.)

Tesi's protector Prince Joseph Friedrich of Saxe-Hildburghausen. Engraving by Johann Christoph Sysang (A-Wn, NB 520130-B)

The Auersperg Palace, which, from 1760 until 1777, was rented by Prince Saxe-Hildburghausen. Colored etching from 1780 by Johann Ziegler (A-Wn Pb 207586-F.Por., Tafel 18)

"Prospect deß Gebäues Ihro Excell. Tit: Herrn Herrn Marquis de Rofrano, Printz von Copece". From Salomon Kleiner's Wahrhaffte und genaue Abbildung Sowohl der Keyßerl: Burg und Lust-Häußer, als anderer Fürstl. Und Gräffl. oder sonst anmuthig und merckwürdiger Palläste (Augsburg 1725)

The Auersperg Palace around 1883, before the stylistic defacement of its middle section by Carl Gangolf Kayser (Wien Museum I.N. 29321)

In his memoirs Lebensbeschreibung. Seinem Sohne in die Feder diktiert (Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1801), the composer Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf, who was to become one of Tesi's greatest admirers, recounts his very first meeting with the singer in 1751, at Prince Saxe-Hildburghausen's palace. The following quotes from Dittersdorf's memoirs are taken from Arthur Coleridge's translation The Autobiography of Karl von Dittersdorf, dictated to his son (London: Richard Bentley and Son, 1896).

On the morning of March 1, 1751, my father took me to the palace of the Prince, in whose service I was, to start me on my new career. The Prince was not at home, and we were referred to the steward, Johann Ebert, a very dignified and respectable person, who had had orders to receive us. He was specially commissioned to look after me, and Bremer, Clerk of the Chancery, was to assist him; so, after some words of advice, given in a very fatherly tone, he took me off to Bremer's room. [...] I felt not a little pleased with myself, when the Court steward placed me in front of a large mirror, and I could get a full view of my new turn-out. Fine feathers make fine birds. 'It is close on eleven o'clock,' said he. 'Go into the music-room; the rehearsal is about to begin.' I went in, and found most of the orchestra already assembled. One and all overwhelmed me with congratulations on my promotion to the office of Kammerknabe. I was now one of themselves. I was the happiest of mortals.The steward Johann Ebert, who looked after Ditters, we shall encounter again later in this blogpost. The "clerk of the chancery Bremer" was Johann Georg Bremer, "Cassier bei Seiner Hochfürstlichen Durchlaucht", son of Christoph Bremer, a chamberlain of the Prince's father Ernest, Duke of Saxe-Hildburghausen. The musician Hubaczek, who accompanied Ditters in his recital, was the Prague born horn virtuoso Wenzel Hubaczek who had brought Ditters into Saxe-Hildburghausen's orchestra and whose brother Johann (1731–1765) was also a horn player in the Prince's service. Wenzel Hubaczek lived at the Prince's palace and had a close friendship with Vittoria Tesi who in 1763, served as godmother at the christening of the second child of Hubaczek and his wife Catharina, née Nagerl.

The symphony was only just over, when Madame Tesi appeared. Bonno had recently composed two airs for her, and she wanted to try them. Though now over fifty years of age, she was still good-looking and pleasant. Bonno, after placing the music on the desk, sat down at the clavicembalo, and Madame Tesi stood behind him. She had a full, clear contralto voice, and her fine singing completely carried me away. When the song was ended, she sat down in front of the orchestra and talked to the Kapellmeister. 'Madame Tesi would like to hear you play,' he called out to me.' Have you any music with you?' Yes, I answered, and fetched a sonata of Zügler's, in which Hubaczek accompanied me. Tesi soon began to call out 'Bravo!' at every successful passage, and afterwards 'Bravissimo!' Then she asked to be introduced to my father, and talked French to him for a little time. After a few instrumental pieces, she went up to the clavicembalo, and sang the second air an adagio. I had been charmed by her brilliant execution in the first instance, and I was now so moved by the tenderness and sweetness of her expression, that I thought music could go no further.

The entry concerning the baptism of Maria Victoria Hubaczek on 18 March 1763, at Vienna's Piarist Church (Maria Treu, Tom. 3, 303).

d[en] 18 Ist von P. Conradus g.[etauft] w.[orden] Ma[ri]a Victoria Josepha / Vat.[er] Wenceslaus Hubatzek ein Waldhornist bey / den Prinzen Hildburgsh:[ausen] im louvaranischen [Rofranischen] Garten / Mutt.[er] Catharina Ehw.[eib] Gev.[atterin] die Hoch und Wohl= / geborne F[rau] F.[rau] Ma[ri]a Victoria Tesy anstatt der[e]n / Anna Ma[ri]a Zickin ledigen Standes. Heb.[amme] Kricklin

On the 18th, baptized by father Conradus. Maria Victoria Josepha. Father Wenceslaus Hubatzeck, a hornist with Prince Hildburghausen in the Louvaranischer garden. Mother Catharina his wife. Godmother the high and well-born lady Mrs. Maria Victoria Tesy, substituted by Anna Maria Zick, an unmarried woman. The midwife was Mrs. Krickl.

Tesi's Josephite Marriage

Apart from a few second-hand accounts of somewhat fairy-tale nature, there is not much reliable information concerning Tesi's private life. The pivotal part of her biography, the story that no writer was ever able to ignore, is the popular tale of how, in order to fend off the advances of an undesired nobleman, Tesi married a simple Italian. The story appeared in print for the first time while Tesi was still alive: in his book about his second European tour The present state of music in Germany, the Netherlands, and United provinces (London: T. Becket and Co. 1773), Charles Burney included it in the account of his stay in Vienna, claiming that "he had obtained the particulars from a person of high rank, who has resided at Vienna so long, that he is perfectly acquainted with the history of musical people". In Burney's version the nobleman's identity is not revealed, and Tesi's future husband is described as "poor journeyman baker" who was picked off the street and paid fifty ducats for marrying the singer, "not with a view to their cohabiting together".

Charles Burney's account of Tesi's emergency marriage (Burney 1773, 318f.)

Chapter IV of Dittersdorf's memoirs is entirely dedicated to Vittoria Tesi. After dealing with Tesi's career and the experiences of her trained parrot in 1738, with the Spanish Inquisition, Dittersdorf, in a paragraph, titled "Ein Herzog wird vom Theaterfriseur ausgestochen" ("A Duke outdone by a theater coiffeur"), addresses Tesi's moral qualities and her married life (the following quote is again taken from Coleridge's translation).

Tesi's character was above reproach. She was utterly unlike the ordinary run of operatic singers. I could tell many things that redound to her honour, but will content myself with the story of her marriage, which, at any rate, will show her in no common light.In Dittersdorf's account the baker has become "the stage barber Tramontini", but it is to be noted that, like Burney, Dittersdorf does not specify the time and place of Tesi's wedding. That the nobleman's name is given as "Duca di N." points to Italy as the location of the events. A strong Viennese flavor was added to the story of Tesi's marriage, when in 1858, the writer Moriz Bermann used it for a short article, titled Eine Opernsängerin der "alten Zeit.", which on 30 March 1858, he published in the journal Blätter für Musik, Theater und Kunst. With great persuasion, Bermann changed Tesi's year of birth to 1690 and relocated Tesi's wedding to Vienna in the year 1720, a time when Tesi was probably still engaged in Dresden. Since the unwanted nobleman had to be a local, Bermann declared him to have been Count Johann Ferdinand von Lamberg (1689–1764), managing director of the court orchester, the so-called "Musikgraf". Bermann even went so far as to describe how Tesi – in search of a future husband – went to the Glacis in front of the old Burgtor and asked a group of laborers, "if there was an Italian among them". In 1881, Bermann pubished the story again in his book Maria Theresia und Kaiser Josef II. in ihrem Leben und Wirken. For his article about Tesi which was published in 1882, in vol. 44 of his Lexikon, Constant von Wurzbach gladly copied Bermann's "Viennese version" of Tesi's marriage and from Wurzbach's Lexikon the story found its way into the popular literature. That something must be amiss in Bermann's scenario, was first pointed out by Gustav Gugitz in his book Giacomo Casanova und sein Lebensroman (Vienna: Verlag Ed. Strache, 1921). Since Count Lamberg, in 1721, married Baroness Maria Franziska von Gilleis (widowed von Schallenberg and von Grundemann, 1691–1760), Tesi's wedding must have taken place before 1721. But this date is at odds with the year of birth of her husband Giacomo Tramontini, who, according to his age given in the records at the time of his death, was born around 1705. The evidence that can be drawn from Viennese archival sources concerning Tesi's marriage is conclusive: because Tesi's wedding did not take place in Vienna, the story about Count Lamberg's courtship must be a piece of fiction. It is very likely that Tesi married Giacomo Tramontini in Italy around 1730, and the sources suggest that this wedding probably took place in Padua where Tramontini owned a house. Giacomo Tramontini and the financial provision he allegedly received from his wife will be dealt with below.

Wherever she sang, she was accustomed to receive all sorts of visitors, but she knew how to make it very difficult for anyone to speak of love. She had plenty of admirers, and the most ardent amongst them was the Duca di N. He happened to find her alone one evening, and used his opportunity to make a formal declaration. Tesi gracefully and courteously refused to have anything to do with him. The Duke, however, believing the refusal a mere feint, became all the more importunate, and promised more and more. Tesi answered him with such dignity, and was so conscious of commanding respect, that the Duke was abashed, and withdrew, never venturing again to renew the attack. His passion continued it increased every day and the oftener he saw and heard the charming creature at the theatre, the more he loved. He made a confidant of one of his courtiers, who tried to negotiate in his master's favour, but was so sternly rejected that he, as well as the Duke, was forced to realize the hopelessness of getting at the lady by such means. 'I am determined to win,' said the Duke, 'even if I have to marry her before all the world! Tomorrow evening I will surprise her with a formal offer of marriage; but take care she knows nothing about it.' –– Of course the supple courtier promised the strictest silence; but, thinking to curry favour with his future Duchess, he went off there and then to Tesi, and imparted to her, in the most sacred confidence, the great secret which was weighing upon his mind.

But what did Tesi do? To be quit of the Duke's importunities once and for all, without coming to loggerheads, she summoned to her aid, that same evening, the stage barber, a good-looking man, and formally offered to become his wife. 'If you will have me' said she to the delighted and astonished Tramontini, 'here is my hand! We will be married straight off, early to-morrow morning. I will give you a good round sum of ready money. Deal with it as you please; it shall be yours absolutely, together with all the interest. I will do the housekeeping, and look after your clothes and your furniture. Besides that, one-third part of my present fortune, and anything I may add to it in the future, in money or the worth of money, shall be legally assured to you; but I stipulate once and for all (and I shall not change my mind) that we live apart, though man and wife in law. [Here Coleridge cuts the following passage from his translation: "A bodily failing, not incurred through loose living but brought into the world with me, renders me quite incapable of entering into such a relation."] If, after this stipulation, you will give me your hand, we will be married to-morrow. You shall have till to-morrow morning early for reflection.'

It may easily be supposed that the delighted barber gave her both hands instead of one. The very next day, at nine o'clock, the two drove off to the Bishop, to obtain his sanction; the wedding was to be celebrated in the nearest parish church they could find. The license was obtained without difficulty, on explanation, and they were married at eleven, after which the lawyer, who was waiting for them at home, drew up a contract for them to sign and seal. The wedding breakfast over, Tramontini's goods and chattels were transferred to Tesi's quarters, and she counted out to her enraptured husband two thousand zecchini in hard cash.

The surprise and embarrassment of the Duke may well be imagined, when he came back in the evening, to see the transformed Tramontini, in his Sunday best, sitting familiarly beside his adored Tesi, and to hear from her own lips the solution of the fatal riddle. She did her task delicately, and he put a strong restraint on himself, so as to try and appear politely indifferent; but it was impossible to conceal the feelings of wounded pride. He bade her a haughty good-bye soon afterwards, and never came back again.

Tesi and her husband lived quite happily together. For many years they were in the Prince's palace, until His Highness returned to Hildburghausen and assumed the guardianship of the young Duke, who was still a minor. Age and infirmity prevented her from undertaking so long a journey; so she parted with her illustrious friend and remained in Vienna, where she died a few years afterwards. The property she left behind her amounted to nearly three hundred thousand gulden, of which her husband inherited one-third, by virtue of the contract. Who got the rest, I cannot say; but whoever it was, he had to pay her servants double wages as long as they lived, and to give them her wardrobe, to be divided in equal shares.

Sleep softly, glorious woman! Let me honour thy memory to my last breath!

Vittoria Tesi Tramontini's Will

On 10 April 1773, Tesi Tramontini summoned her personal notary, the protonotary and auditor at the Papal nunciature in Vienna, Giuseppe Antonio Taruffi, together with a scribe (although certain features of Taruffi's handwriting suggest that he himself wrote Tesi's will), and had a will drawn up that consists of fifteen paragraphs on six and a half pages. As far as legal matters were concerned, Tesi Tramontini seems to have had very good advisors. Shortly before her death, she submitted a petition to the I. & R. State Council (A-Whh, Staatsrat, 1581/1775, 2232/1775 – these files were destroyed in 1945 in a depository in Obritzberg), requesting that the distribution of her inheritance should not be taken care of by the Court of the Landrechte, but by the City of Vienna's civil court which was responsible for non-noble citizens. By doing this, she precluded her husband, who is addressed as "von Tramontini" in many sources, from passing himself off as nobleman. She also saved taxes and facilitated the legal procedure in the interest of her heirs. On 9 May 1775, at 4.30 p.m., Tesi Tramontini died at Josephstadt 1. The official death records give pneumonia as cause of death. That the deceased had been "65 years of age" (as given in the Totenbeschauprotokoll and the burial register) is obviously false.

The entry concerning Tesi Tramontini's death in the municipal death records (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 69/1, DT, fol. 15r)

Den 9t / Maÿ 775 / Tesi Tramontini, Wohledlgebohrne Frau / Victoria, ist im Roforanischen / Garten N: 1. in d[er] Josephstadt, an / d[er] Lunglentzündung besch[aut] word[en] / alt 65 J[ahr] Abends um 1/2 5 Uhr versch[ieden] / F:[ranz Anton] S:[chmid]

Tesi Tramontini was buried in the city, in the crypt of the Capuchin Church on the Neuer Markt. This privilege was made possible by a Mass endowment of 1000 gulden to the Capuchin Convent which established a perpetual fund to finance regular readings of masses for the intercession of Tesi's soul.

The entry concerning Vittoria Tesi Tramontini's death and her burial in the crypt of the Capuchin Convent in the records of the Piarist Church (Maria Treu, Tom. 2, fol. 654). The Capuchin crypt was a popular burial site among wealthy Italians, such as, for example, the architect Donato Felice d'Allio. Metastasio was buried in the crypt of St. Michael's, because he was a tenant of the Barnabites.

On 10 May 1775, Tesi Tramontini's will was submitted to the Judicium Delegatum Militare Mixtum (the I. & R. Military Court) and published in the presence of the Court agent Johann Matolai von Zsolna (1692–1777). After its transfer to the municipal authorities on 11 October 1775, the will was published a second time at the civil court with the advocate Dr. Johann Baptist Prati (1736–1789) as witness. Apart from the obligatory pious legacies and the bequests to her relatives and her husband – whom she appointed universal heir – the central objective of Tesi Tramontini's will was to secure the subsistence of her brother Giovanni who needed permanent care, because he was deaf, mute, and mentally handicapped. Tesi Tramontini was deeply worried that, after the possible death of his close relatives, her brother Giovanni would be left alone without anybody being able to take care of him. Thus, Tesi appointed her patron Prince Saxe-Hildburghausen, Count Cristoph von Cavriani and Count Maria Carl von Saurau executors of her will and gave them exact directions concerning the care for her brother and the safeguarding of his livelihood. To support her handicapped brother, Tesi ordered a sum of eight thousand gulden from her heritage to be deposited in the Vienna Treasury and the annual interest of three hundred and twenty gulden to be used for the subsistence of her brother Giovanni.

The first page of Vittoria Tesi Tramontini's will (A-Wsa, AZJ, A1, 14694/18. Jhdt.). The last line is Tesi Tramontini's autograph signature which appears at the bottom of every page. A free German translation of this document, which in 1777 was made for the civil court, survives in the holdings of the old registry (A-Wsa, Alte Registratur, 188/1777).

The translation of Tesi Tramontini's will (whose original Italian text can be downloaded here) reads as follows (for better readability the fifteen paragraphs have been divided by space lines).

In the Name of the Holy Trinity,

The Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost!

published on 10 May 1775

Considering that nothing is more certain than death and nothing more uncertain than its time and hour, I, Vittoria Tesi, wife of Giacomo Tramontini, currently (by the grace of the Most High) in good physical and mental health, take advantage of this favorable state of mind, and in full power to reflect and resolve, I came to the deliberate and spontaneous decision to take advantage of my good health that God, in His divine mercy gives me, and without any suggestion or persuasion, I am determined, to make my will of the below content, revoking, retracting, and cancelling all my previous testamentary dispositions, be they written by my own hand, or by the hand of others. Thus I decree and without any exception want to put my last will into effect, as follows:

First, I commend my soul to God, my Creator and Redeemer that, by the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary, He may receive it in His peace and glory.

Second, I want my body to be buried at the Capuchins', according to the rites of the Holy Catholic Church, without pomp, at the expense of my universal heir which I will name below, and that

Third, at my obsequies hundred holy masses should be read as intercession for my soul.

Fourth, I bequeath one thousand gulden to the Church, or to the Capuchin Convent in the City of Vienna to establish a basically perpetual fund from whose annual interest the amount should be deducted to pay for the number of masses for my soul that the executors of my will (who will be appointed by me below) will agree upon with the Capuchin Friars.

Fifth, I bequeath to each of the five Viennese poorhouses two Viennese gulden. And likewise I declare that, because all [fol. 1v] my possessions and goods, namely consisting of cash, bonds, jewelry, silver, clothes, lace, linens, furniture, and other belongings, are completely free from any liability and entirely under my absolute disposal, I decree,

Sixth, that according to the direction and the most appropriate judgement of the executors of my last will, from my heritage a sum of three thousand Viennese gulden should be set aside to constitute a decent legacy for my nephew Alessandro, my brother Cosimo's son, under the explicit condition that, during his lifetime, every week, my nephew Alessandro must read a mass for my soul. And in the case of him being indisposed, or otherwise impeded, I put him under the obligation to have another priest read the same weekly mass for the salvation of my soul. At the end of his life, I grant him the freedom to bequeath the said sum of three thousand gulden as he wishes. And in case he should die without a will, the said asset should go to my universal heir, or his heirs to infinity.

Seventh, I establish, order, and want, that the sum of eight thousand Viennese gulden should be put aside from my heritage and this sum should remain, or be redeposited in the Vienna Treasury at an interest rate of four percent, from which, at the discretion of my executors, the annual interest of three hundred and twenty gulden should be used for the subsistence of my poor brother Giovanni, who, because of having the misfortune to be deaf-dumb and mentally handicapped, needs the most special care, a matter that will forever be close to my heart; and since my dear husband, Giacomo Tramontini, took every care of my aforesaid poor brother and gave him free accomodation in his house in Padua, I hope, he will also provide the same care in the future, however with intelligence [fol. 2r] and under the direction of my executors, and will always provide free lodging in his said house in Padua. In case my brother Giovanni should die before my universal heir, I want the latter to remain in absolute disposition of the aforementioned sum of eight thousand Viennese gulden and he can dispose of it as he pleases. And finally, if my brother Giovanni survives my universal heir, I want the heirs of my heir to remain the absolute owners of the respective sum of eight thousand gulden, whenever God calls said Giovanni to eternity, with the obligation however, to always let him (as it is now) stay for free in their said house in Padua, and, during his lifetime, they can touch neither the capital nor the interest of the said sum, that the capital must always remain in the bank and the interest is to be used for his subsistence in the aforesaid way.

Eighth, to my married brother Cosimo I bequeath a sum of two thousand Viennese gulden.

Ninth, to my niece Vittoria, daughter of my aforementioned brother Cosimo, who was held by me at the sacred baptismal fountain, I bequeath the sum of two thousand Viennese gulden to be invested in the Bank of Vienna. She alone, as long as she remains unmarried, will be entitled to receive and enjoy the interest of this capital. I determine and want that, if she contracts an appropriate marriage, the same capital of two thousand Viennese gulden passes entirely into her possession. And to rule out any legal dispute or problem in this matter for my beloved niece and goddaughter, I expressedly exclude her father and her stepmother from any abitrariness or right to touch even a kreutzer of this sum of two thousand gulden, be it the capital or the interest [fol. 2v], my firm will being that Vittoria herself alone should enjoy the capital and the interest in the respective manner that has been described above. Should the said Vittoria die unmarried, I mean and I want that she keeps full freedom to dispose of the sum of two thousand gulden, in such a way that nobody can presume or impede her right. Furthermore, I leave to my same niece two lace bonnets, one from Venice, one from England, and a third one, made of lace from Mechelen.

Tenth, to my moor Maria, whom I have raised since she was a girl, and who has faithfully served me for so many years, as reward for her long service and her sincere affection for my person, I bequeath my whole wardrobe, consisting of clothes, dressing gowns, small coats, caps, blouses, handkerchiefs, stockings, made of of silk and wool, undergarments, shoes, sheets, and towels, except the pieces of clothing of which I dispose otherwise in the context of my will. Then I declare again that the bed on which this black maid sleeps, with all the accessories, all the furniture and paintings which are in her room, as well as the sacred pictures and crucifixes in my room are all things that I bequeath to her. Furthermore I attest that the said moor owns a small capital of forty sequins which is held by my husband. Finally I leave to the said moor Maria the sum of two thousand Viennese gulden in full ownership and freedom of disposition. Of course, this sum of two thousand gulden does not include her aforementioned small capital of forty sequins.

Eleventh, to my servant Giovanni I bequeath the sum of one hundred Viennese gulden.

Twelfth, another sum of one hundred Viennese gulden I bequeath to my servant Josefa, commonly named Sepperl, to whom I also leave two ordinary dresses, twelve blouses, twelve pairs of thread stockings and twelve linen handkerchiefs. [fol. 3r] Then I decree and want

Thirteenth, for the fulfillment of all the above mentioned and the paragraphs 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. and the stipulated provisions, or legacies, preferably the cash at hand should be used and my capital in the Bank of Vienna, up to the amount which can suffice; and in case this is not enough, the silverware should be sold and then the jewels, to use the money of this sale for the fulfillment of my aforesaid legacies, given what I want, and I want that these should be fulfilled before everything else. These explicit legacies should be deduced without exception from my hereditary assets. I determine

Fourteenth, I appoint, and declare as my universal heir of all the rest of my possessions and goods, my most beloved husband, Giacomo Tramontini; he truly, will remain the master and owner ever after my death, under the explicit and positive condition however, that my said husband has to continue:

1st, to take care of my poor dumb brother under the guidance of my executors, with the use of the three hundred and twenty gulden annual interest, designated for his substistence, to be willing to keep it up with the same care and charity that he has so far shown to him and to always provide him with free accommodation in his house in Padua; moreover he has to

2nd, pay from his share of the heritage all fees imposed by the government, all costs arising for my funeral and all the necessary expenses without exception, while I do not want that my other dispositions and legacies should be put under any burden. And although I am convinced that nothing will be needed to be said about the quarta falcidia, I still

3rd, want to renounce the law of quarta falcidia for my heir, even if, against my expectation, after all deductions have been subtracted, his share of the inheritance should not amount to this quarter. And although I know the good heart of my [fol. 3v] most beloved husband well enough to be sure that he will agree to everything which has been expressed so far, I do, however, declare and positively establish that, if ever, against all odds, he would let himself be induced by some bad advice, under any conceivable pretext, to want to oppose and contradict in toto, or in parte, the provisions made by me in this my will, as well as countervene even the smallest paragraph in it, with that same will I declare him excluded from all the inheritance, and in his stead I appoint the son and daughters of my brother Cosimo heirs in equal shares.

Fifteenth, finally, to have this my last will executed on time and unaltered in all its parts and according my true intention: I appoint and name as my testamentary commissioner and executor of the my above will, in the first place, the most serene Duke Joseph Friedrich of Saxe-Hildburghausen, my most gracious master, humbly begging His Highness to deign to take on this charitable and kind task and give me the last proof of His kindness towards me, by procuring to effectively fulfill all my provisions. His serene Highness will similarly appoint in accordance with His consummate prudence, one or more prominent individuals to replace him and to secure the unfailing execution of my abovementioned intentions. Similarly, after my most gracious master, I institute as executors of my wills His Excellency, Count Cristofero[sic] Gabriani[sic] and His Excellency, Count Carl Maria Saurau, as both of these Excellencies have graciously granted their permission and given their promise. These my respected executors were requested by me to graciously and kindly concur in the fulfillment [fol. 4r] of all these my dispositions, above all, the one which concerns my poor deaf and dumb brother Giovanni, who is in need of everything and all other assistance, so that he will not suffer from the smallest fraud or abuse from human malice, but will always be supported, guarded and assisted with every punctuality and lovingness, until it pleases God to call him to the other life, and therefore, I leave them the full right to make appropriate changes during his life, that after the death of my husband, the care for my said brother, entrusted to him and then to his heirs, will be given in the hand of somebody qualified, in case that this poor creature should not be assisted with the care and attention that I want.

All this I corroborate, establish, ratify and respectively recommend, I, the undersigned. Vienna 10 April 1773

[L.S.] Vittoria Tesi Tramontini[L.S.] Federigo Baron of Bülow

requested witness

[L.S.] I Giacomo d'Aquino Duke of Casarano requested witness

[L.S.] I Giuseppe Antonio Taruffi apostolic protonotary and auditor at the nunciature in Vienna, requested witness mp

The seals and signatures on the last page of Tesi Tramontini's will (A-Wsa, AZJ, A1, 14694/18. Jhdt.)

The fact that Giovanni Tesi lived in Giacomo Tramontini's house in Padua, suggests that Tramontini was originally from Padua and Tesi Tramontini had her brother move there from Florence.

The witnesses of the will

The identity of the witnesses of Tesi Tramontini's will sheds more light on the singer's social environment about which previously we knew very little.

The closed envelope of Tesi Tramontini's will with the seals and signatures of the testatrix and her three witnesses

The three witnesses were the following:

- Ferdinand Friedrich Baron von Bülow was a member of the Ugahlen line of the Zibühl branch of the large Bülow family. He was born on 12 August 1711, in Courland, probably in Ugahlen (today Ugāle in Latvia), eldest son of Friedrich Gotthard von Bülow and Anna Katharina, widowed von Behr, née von Firks auf Lehsten und Alt-Autz. In 1731, he joined the Austrian military as officer of the Hildburghausen Infantry and showed extraordinary bravery against the Turks in the Battle of Grocka. In the War of the Austrian Succession, in the Battle of Pfaffenhofen, he distinguished himself with such excellence that, skipping the rank of major, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. In 1746, he took part in the Austrian invasion of the Provence and in 1747 in the Siege of Genoa. After the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, Bülow returned to Courland and in 1751, after having been promoted to colonel, became commander of a regiment. The Seven Years' War earned Bülow great fame. His meritorious service in the battles of Lobositz, Prague and Breslau led to his appointment as commander of Liegnitz. After the Prussian army had retaken Breslau, Bülow was requested personally by the Prussian king to surrender, but refused and threatened to defend Liegnitz to the last man, unless he was granted unhindered withdrawal together with his artillery, munition, and baggage. The king, who admired such sturdiness and realized that he would risk unneccessary losses and the destruction of the town, on 28 December 1757, agreed to all of Bülow's conditions and even had the Austrian garrison escorted to the Bohemian border via Jauer and Liebau. In 1758, Bülow was promoted to general major and awarded the Military Order of Maria Theresa. In 1758, during the Siege of Olomouc, he was able to sucessfully reinforce the town's defence forces with 2000 men which led to his promotion to field marshall lieutenant. In 1773, he was appointed general of the branch. Friedrich Bülow never married. On 19 June 1776, he died commanding general in Brussels. Bülow's presence at the Rofrano palace may have been related to his having been colonel-commander of Prince Saxe-Hildburghausen's infantry regiment from 1752 until 1758.

- Giacomo d’Aquino, il quinto Duca di Casarano was born on 7 June 1716, in Naples, fourth child of Giacinto d'Aquino, 4° Duca di Casarano (d. 13 March 1740) and Raimondina, née Belli. The d'Aquinos were a Neapolitan family that originally came from Taranto, and in 1637 received the predicate "Duca di Casarano". In 1723, d'Aquino's father sold the duchy, but kept the title. The reason of d'Aquino's stay in Vienna is yet to be revealed. That he had connections to Vienna already in 1762 is documented by his wedding on 2 February of that year at St. Stephen's Cathedral. The most important Viennese source related to d'Aquino's biography is the entry concerning his marriage to Countess Josepha von Althann. The Countess was a born Mitrowsky von Mittrowitz und Nemischl, second wife and widow of the k.k. Obrist-Silberkämmerer Count Johann Albert Anton von Althann (1700–1761). Giacomo d'Aquino was not present at his wedding. He was married by proxy, being substituted by the Spanish ambassador to the Imperial Court, Count Demetrius O'Mahony (1702 – 25 December 1777). The officiating priest was the then archbishop and Papal nuncio Vitaliano Borromeo.

The entry concerning the wedding on 2 February 1762 of Giacomo d'Aquino Duca di Casarano and Countess Josepha von Althann, née Mitrowsky von Mittrowitz und Nemischl (A-Wd, Tom. 60, fol. 205v)

-

Giacomo d'Aquino seems to have returned to Naples where in 1780 he is said to have married a second time. He died on 26 October 1788, in Italy.

- Giuseppe Antonio Taruffi was born in 1722, to a Bolognese family that originally came from Bagni della Porretta (today Porretta Terme). His parents were Giovanni Niccolò Taruffi and Anna, née Bartoli. Taruffi attended the Jesuit school in Bologna where he demonstrated extraordinary talent and excelled in his studies of Latin and ancient Greek. In his youth he felt an inclination towards priesthood, but abandoned the idea for the time being. More out of obedience than inclination he followed the wish of his father, who had studied law under Metastasio's adoptive father Giovanni Vincenzo Gravina, he went to Rome where on 7 April 1739, he acquired a doctorate in law. He did not become a full-time lawer, however, but spent most of his time studying languages, such as French, English, and Spanish. Three years later, after the death of his father, Taruffi returned to Bologna to fully dedicate himself to literary studies, the writing of poetry, and the publication of Lettere in the tradition of Pietro Aretino. In 1765, the papal nuncio in Poland (and future cardinal), Monsignor Antonio Eugenio Visconti, whose acquaintance Taruffi had made during his stay in Rome, offered him a position as secretary. Taruffi accepted the offer and moved to Warsaw where, apart from his administrative work at the nunciature, he dedicated himself to studying the Polish and German languages. In November 1766, when Visconti was appointed papal nuncio in Vienna, Taruffi followed his superior to Vienna where he was promoted to the rank of authenticating officer and auditor at the nunciature. Taruffi was an avid chess player and in 1770 he left a mark in chess history by describing von Kempelen's chess automaton The Turk which he had witnessed in action in Vienna. After the death of Pope Clement XIV, nuncio Visconti had to leave Vienna to take part in the conclave that convened to elect the new pope. Because Visconti had been appointed cardinal at the titular church Santa Croce in Gerusalemme and became prefect of the Congregazione della Propaganda Fide, he resigned as nuncio and did not return to his post in Vienna. For a time of twenty months, from 24 October 1774, until the installation of the new nuncio Bishop Giuseppe Garampi in 1776, Taruffi was in charge of the Vienna nunciature and bore the title "Internunzio of the reigning Pontifex". In 1776, he returned to Rome and dedicated his remaining years to literary studies and poetry. In 1782, he published an Elogio Accademico on the death of Metastasio (which he dedicated to cardinal Visconti) and in 1784, Montgolferii Machina Volans, an elegy about the Montgolfier brothers' balloon. Taruffi died on 20 April 1786 in Rome.

-

Taruffi was no stranger to musical life in Vienna. It was Taruffi, who in 1772 told Charles Burney about Marianna Martines's exceptional musical abilities and accomplishments, and made him visit the composer in Metastasio's apartment. Taruffi was a close friend of his fellow Bolognese Padre Martini with whom he was acquainted since his early youth. In 1773, following Metastasio's preparatory correspondence, Taruffi established the personal connection between Marianna Martines and Padre Martini which led to her becoming a member of the Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna. On 19 April 1773, Martines wrote the following to Padre Martini:

It needs no less than the magisterial authority of Your Most Illustrious Reverence in order that I may believe myself permitted the boldness to desire a place for my name among those of the illustrious Philharmonic Academicians. The most worthy Signore Auditor Taruffi assures me that you, in an excess of partiality, are procuring for me that enviable honor. Wherefore, in consequence of his hints I am sending you a psalm for four voices written by me with whatever careful precision I am capable. (Godt 2010, 135)

The executors of the will

Count Christoph Franz Theodor von Cavriani (the spelling "Gabriani" in Tesi's will is a corruption), Baron of Unterwaltersdorf, was born on 1 April 1715 (A-Wd, Tom. 57, fol. 1v), in Vienna, son of Leopold Karl von Cavriani and his wife Susanna, née Baroness von Gilleis. Christoph von Cavriani, who belonged to the Bohemian line of the Cavrianis, had a family relation to the abovementioned Giacomo d'Aquino: his cousin, the Imperial lady-in-waiting Rosalia von Cavriani (1718–1744) was the first wife of Count Johann Albert Anton von Althann, the first husband of d'Aquino's wife. At the time of his appointment as executor of Tesi Tramontini's will, Cavriani held the office of "Obristlandrichter in Niederösterreich" (superior judge of the Lower Austrian Landrechte court), a post that he had been appointed to on 26 September 1764 (A-Whh, OMeA ÄZA 63-13-2). According to the Portheim catalog, Cavriani died on 5 September 1783, in Senftenberg, but the church records of this village do not corroborate this information.

Count Maria Karl von Saurau was born on 6 August 1718, in Graz (Hl. Blut, Tom. 12, 621, the date in Wurzbach vol. 28 is wrong), son of Maria Karl von Saurau and Maria Katharina, née Countess von Breuner. In 1775, Saurau was Court Councilor, Chamberlain, and "Obristhofmarschall-Amtsverweser" (substitute Obersthofmarschall). He died of inflammatory fever on 2 November 1778, in Vienna. Saurau and his wife Maria Antonia, née Countess von Daun, were the parents of Count Franz Joseph von Saurau who in 1797 commissioned Haschka and Haydn to write the Kaiserhymne.

Cavriani and Saurau were probably friends of Prince von Saxe-Hildburghausen. Since the literature on Saxe-Hildburghausen, the main executor of Tesi Tramontini's will, is quite extensive, his biography will not be dealt with in this blog post.

Tesi Tramontini's estate

Tesi Tramontini's Sperrs-Relation (probate file) is structured according to the administrative rules of the k.k. Stadt- und Landgericht (old municipal court of justice) that were valid until the Josephinian reform of the justice system in 1783. The file consists of the cover sheet, the so-called Mantelbogen, a thirty-two-page "Raithandler-Bericht" (auditor's report) to the City Council, submitted on 13 November 1776, that consistsof a list of Tesi's assets and a summary of her testamentary dispositions (including the details of their fulfillment). Part of this file is "attachment E.", a four-page final Beeÿdigungsmässige Bekandtnuß (solemn declaration) concerning the assets of the deceased, dated 1 March 1776, and signed by the universal heir Giacomo Tramontini. Four other attachments F-I (bills and receipts concerning the bequests), that are referred to in the report, do not survive. "Attachment K" was the abovementioned German translation of the will that survives in the Hauptregistratur. The cover sheet of the Sperrs-Relation, which was drawn up and submitted on 13 May 1775 by the City Council's Supernumerarius Dominicus Crammer (the office of Sperrs-Commissär did not exist yet), begins with Tesi Tramontini's name and the following notes concerning her profession and marital status:

Profession according to the death records without any, but it was found out that she is said to she have been employed as singer for 24 years with His Serene Highness Prince von Saxe-Hildburghausen.

Marital status married, the widower is Mr. Jacob Tramontini, who lives of private means in the Leopoldstadt in his own house, having neither an employment nor a patent of nobility.

The front page of the cover of Tesi Tramontini's Sperrs-Relation (A-Wsa, Alte Ziviljustiz, A2, 300/47)

The date of hearing concerning Tesi Tramontini's estate took place in late 1776. The City of Vienna was represented by the counselor Johann Heinrich Schubert, Giacomo Tramontini (who at that time was in Italy) by his lawyer Dr. Johann Baptist Prati, and the three executors of the will by the lawyer Dr. Philipp von Fabert. Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf must have had trustworthy inside information, when he stated in his memoirs that Tesi Tramontini "left behind nearly three hundred thousand gulden". Although Tesi Tramontini's estate only shows about a tenth of this amount, Dittersdorf's claim still appears to be realistic. Giacomo Tramontini's estate records suggest that already before her death – if Dittersdorf's information concerning her wealth is correct – Tesi Tramontini had transferred most of her assets into the property of her husband. The singer's estate and its value (in gulden and kreutzer) can be summarized as follows:

Cash: 631 fl 30 xThe taxable amount of the inheritance was 29,973 fl 36 x from which the following taxes were subtracted:

Securities and bonds (including interest): 17,114 fl 30 x

Jewelry and valuables 12,227 fl 36 x

Clothes, linen, furniture and movables: 1,146 fl 47 x

Total: 31,120 fl 23 x

Death tax: 155 fl 3 xAfter the payment of taxes, the fulfillment of the bequests, and the covering of all additional expenses (for the burial, the masses and the evaluation of the jewelry), Giacomo Tramontini was left with a net inheritance of 2,620 gulden 6 2/3 kreutzer. This amount was actually higher than expected, because in 1776 it turned out that Tesi Tramontini's brother Cosimo had already died and his inheritance of 2,000 fl fell back to his brother-in-law. The municipal auditor's summary of the will provides information regarding the identity of Tesi Tramontini's servants. The legal full name of Tesi's black maid was Maria Labita. The servant "Giovanni" was a certain Johann Baptist Straner who was born in Gmünd in Carinthia. On 12 November 1765, Straner married Anna Maria Nepot from Vienna (Maria Treu 2, 478). In 1772, in honor of his employer, he named one of his daughters "Maria Anna Victoria".

Office fee: 3 fl

10% inheritance tax: 262 fl (after deduction of fees and bequests)

Einfaches Abfahrths-Geld (simple departure tax, the universal heir being nullius conditionis): 609 fl 57 x

Doppeltes Abfahrts-Geld (double departure tax) of the maiden Vittoria Tesi: 200 fl

Inheritance tax of Vittoria Tesi: 90 fl

Inheritance tax and departure tax of the black maid: 290 fl

Taxes of the servants Giovanni and Josepha: 10 fl

Taxes in total: 1,620 fl

(plus 32 fl annual inheritance tax that the universal heir had to pay for the life-long annual 320 fl interest from the deposited 8,000 fl for which he was requested to deposit a security of 800 fl)

The entry concerning the baptism of the servant Johann Straner's daughter Maria Anna Victoria on 29 November 1772 (Maria Treu, Tom. 4, fol. 25)

The name of Tesi's servant "Josefa, commonly named Sepperl", was Josepha Luschinsky. She was probably a relative of Elisabeth Luschinsky, girlfriend of the actor and singer (and Mozart's first Pedrillo) Johann Ernst Dauer. From Tesi's probate file we also learn that her nephew Alessandro was a priest and was meant to personally read the weekly masses for his aunt.

Giacomo Tramontini

Giacomo Tramontini was born around 1705 in a still unidentified location. It is also still unknown whether he was wealthy and whether the story of Tesi's quasi random emergency wedding with the theater hairdresser is a historical fact. Dittersdorf's description of their marriage as "happy" should be doubted as well. The earliest known source, where Tramontini is referred to as Tesi's husband, are the Neapolitan Erasmo Ulloa Severino's notes of January 1738 that Benedetto Croce quoted in his book I teatri Napoletani. Ulloa delves into Tesi's married life, describes her husband as "soggetto pessimo" (a scoundrel) and reports about an affair that Tramontini entertained with a Florentine lady, and that – with the help of a Bolognese servant and a stable boy – he intended to leave his wife and take all his jewels with him. When Tesi fired both employees, it turned out that not only had the servant her husband's support, he also spoke to her in a bold and very inappropriate way and threatened to scar her face. Tesi informed the general auditor Ulloa of this incident who had this servant arrested and expelled from the kingdom (Croce 1891, 339). This raises the following questions: who in this marriage was financially dependent on whom? Why did Tesi not get rid of her husband? Was the narrative of Tesi's "Josephite marriage" just a tale that she had made up to camouflage the fact that she and her adulterius husband had separated? The image of Tramontini, the poor stage barber, who was raised to a higher social status by a wealthy and famous opera singer begins to unravel as well, when we consider the events after the couple's move to Vienna.

Two pages of a composition of creditors after the death of the Savoyard merchant Franz Goutro in 1766. In the middle on the left is Tramontini's signature, on the right (among others) are the signatures of Gluck's wife Maria Anna and her sister Elisabeth Balbi (A-Wsa, AZJ A2, 2549/5).

On 25 April 1766, Tramontini bought a house with a large garden in the Leopoldstadt (it must be kept in mind that he already owned a house in Padua), had the old house torn down and replaced with two bigger ones. It may well be that his wife financed the purchase, but why – if she really owned the fortune described by Dittersdorf – did she not buy the property herself, move in, and let her husband live in the rear wing of the building? The property Leopoldstadt 359 (today Praterstraße 17) was big enough for a married couple not to run into each other everyday.

Giacomo Tramontini's house and garden Leopoldstadt No. 359 on Joseph Daniel von Huber's 1778 map of Vienna (W-Waw, Sammlung Woldan)

Tesi's Sperrs-Relation states that she had been employed as singer by Prince von Saxe-Hildburghausen since 1751. Where did the couple live between 1751 and 1766, when Tramontini bought his house?

The beginning of the entry concerning the registration of ownership on 7 August 1766 of the house Leopoldstadt 359 by Giacomo Tramontini (A-Wsa, Patrimoniale Herrschaften, B106.18, fol. 240v)

The plot of this house was a quarter of a large garden where in the sixteenth-century galleys were built for the Turkish war. The garden was later owned by Maximilian II who gave it to Count Nádasdy. In 1635, the property was divided into four parts. Johann Wilhelm Lueger of Wasenhoven built a house here which later came to the pharmacist Günther von Sternegg. Today's eighteenth-century building with its late baroque facade was built in 1766 by Giacomo Tramontini. In 1845, buildings were added and in 1846, the property was bought by Count August von Bellegarde, and expanded by the architect Amédé Demarteau into what today is known as the Palais Bellegarde.

Tramontini as owner of Leopoldstadt 359 in the Verzeichniß der um die k. k. Haupt- und Residenzstadt Wien befindlichen Vorstädten, Gründen, Gassen, numerirten Häuser, Innhaber und ihrer Schilder (Wien bey Joseph Anton Edlen von Trattnern, 1778, 103). Note that Tramontini is given as "von". The adjacent house Leopoldstadt 360, which in 1778 was bought by Baron Hugo von Waldstätten, became Countess Waldstätten's abode where Mozart frequently visited.

The south front of the Palais Bellegarde today. On the right is Oskar Thiede's Nestroy monument.

Before Tramontini even claimed his heritage simpliciter absque beneficio legis et inventarii at the municipal court, he married again. On 31 August 1775, he signed a Donations-Instrument (deed of donation) in which he presented his future wife with all his jewelry, "all valuables and silverware in his house", 30,000 gulden in cash, and the house Leopoldstadt 359, including all furniture. His bride, who seems to have been in a waiting position for some time, was Baroness Johanna Nepomuzena von Huldenburg, born around 1735, in Kaschau (Košice), daughter of Theodor Friedrich von Huldenburg, a retired captain of a Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel infantry regiment. The wedding took place on 3 September 1775, at St. Stephen's Cathedral. Tramontini's best man was his lawyer Dr. Johann Baptist Prati.

The entry concerning of Giacomo Tramontini's marriage to Baroness Johanna von Huldenburg on 3 September 1775: "Der Wohl Edle H Jacob Tramontini wittiber cujus uxor Victoria Tesi Tramontini 10 Maij 775 in Parochia Josephina sepulta est." (A-Wd, Tom. 69, fol. 236v). On 11 June 1777, Johanna Nepomuzena Tramontini served as godmother at the baptism of Dr. Prati's son Johann Nepomuk Alois (A-Wd, 93, fol. 283r).

Although Tramontini was a wealthy man, in December 1776 he filed an appeal in the municipal court against the amount of his inheritance tax which he wanted reduced from 262 fl to 71 fl 20 x. This objection had no legal basis and was dismissed (A-Wsa, Alte Registratur, 74/1777). Tramontini did not pay the taxes for some of his first wife's bequests in cash, but had them registered as mortgages on his house.

The departure fees of the heritage shares of Maria Labita, Johann Straner, Josepha Luschinsky, and Tramontini himself, registered on 27 February 1778 as mortgages in the land register of the Herrschaft Bürgerspital in the Leopoldstadt (A-Wsa, Patrimoniale Herrschaften, B106.18, fol. 240v)

Some of Tramontini's various business activities left traces (of somewhat shady character) in the Wiener Zeitung: on 13 September 1780, as an associate and guarantor of the so-called Handgrafenamtspachtungskompagnie (an investment trust associated with the Austrian customs administration), he announced the loss of two original shares of this trust. On 15 December 1784, he reported the loss of six Carten Bianchen (blank checks).

The original poster, issued on 19 November 1784, by the Vienna Magistracy, announcing Tramontini's loss of six blank checks (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A7, 12/1784). This poster was on display from 27 November 1784 until 7 March 1786.

In late 1784, Tramontini informed the public that goods, given to his servants "auf Borg oder Kredit" (on loan or credit), will not be paid, because "he always provides them with cash for their purchases".

Tramontini's note in the Wiener Zeitung of 27 November 1784 concerning his domestic staff

In his will, which he signed on 1 October 1778, Tramontini appointed his wife universal heir.

The final paragraphs of Giacomo Tramontini's will in his own handwriting (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 1798/1785)

Tramontini's most valuable property, his house in the Leopoldstadt, is not addressed in the will, because he had already donated it to his wife. At that time Tramontini's house in Padua had obviously been sold already. Tramontini's will was witnessed by his physicians Leopold Auenbrugger and Bartolomeo de Battisti di San Giorgio.

The signatures of Tramontini's physicians and "requested witnesses", Dr. Leopold Auenbrugger "nobile di Auenbrugg" (a predicate which in 1778 he did not yet own) and Dr. Bartolomeo de Battisti di San Georgio (b. 1755 in Rovereto), on the envelope of Tramontini's will (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 1798/1785)

Giacomo Tramontini died on 29 July 1785 (Wiener Zeitung, 6 Aug 1785, 1854), at 3 a.m. of Schleimschlag (mucoid impaction) and was buried on 31 July 1785 in the St. Marx Cemetery (St. Josef, Tom. 1, 27). During the last years of his life, Tramontini had been a neighbor of Mozart's friend Baroness von Waldstätten who lived at Leopoldstadt 360.

Tramontini as neighbor of Baron Hugo Joseph von Waldstätten in Joseph Maximilian Fischer's Verzeichniß der in der Kaiserl. Königl. Haupt- und Residenzstadt Wien, sammt dazu gehörigen Vorstädten und Gründen, befindlichen numerirten Häusern (Wien bey Joseph Gerold, 1786, 146).

The most important source concerning Tramontini's business activities and financial status during his late years is, of course, his probate file which – similarly to that of his first wife – contains a detailed list of his assets. From this document we learn that Tramontini was a shareholder of the Austrian state lottery. Tramontini's estate can be summarized as follows:

Cash: 1,333 fl 19 x

Due interests from the lottery administration: 166 fl 40 x

Securities, bills of exchange, and bonds (including interests): 96,146 fl 8 1/2 x

Jewelry and valuables: 718 fl

Clothes, linen, tableware, horses, and carriages: 1,795 fl

Total: 100,159 fl 7 1/2 x

Two of Tramontini's bank bonds, at values of 8000 and 2000 gulden, and dated 13 November 1775, can be identified as shares of his first wife's heritage. The first one was used to support Giovanni Tesi in Padua and the second was the share of the deceased Cosimo Tesi that had gone to Tramontini. If Dittersdorf's estimate is correct, and the value of Tramontini's house can be estimated at about 100,000 gulden, about 70,000 gulden of Tesi Tramontini's fortune are not accounted for. But of course, there is absolutely no evidence as to how much money of his own Tramontini had brought into the marriage.

Seal and signature of Johanna Nepomucena Tramontini on her late husband's list of assets (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 1798/1785)

It is interesting to find out what became of Giacomo Tramontini's fortune. On 6 February 1786, Johanna Tramontini, who was now a desirably rich widow, married Baron Maria Ferdinand Gundacker von und zu Aichelburg (b. 1754 in Völkermarkt). The wedding, which took place at the parish church of St. Josef, saw a number of prominent attendants: Cardinal Migazzi officiated, and two of the witnesses were Count Franz Xaver von Orsini-Rosenberg and Count Karl von Zinzendorf (St. Josef, Tom. 1, fol. 47). (The Mozart Dokumente misidentify Maria Ferdinand von Aichelburg as husband of Regine, née Wetzlar von Plankenstern, a subscriber of Mozart's Trattnerhof concerts, but her husband was actually the Croatia-born military officer Baron Joseph Leopold von Aichelburg). In 1788, the house Leopoldstadt 359 was transferred to Baron von Aichelburg who in 1793 sold it to the tailor Leonhard Mathes and his wife Barbara.

A list of the owners of the house Leopoldstadt 359 between 1762 ad 1794 in the Dienstbuch of the Herrschaft Bürgerspital (A-Wsa, Patrimoniale Herrschaften, B 106.9, fol. 78r)

The fact that on 1 November 1797 Baron von Aichelburg died of consumption at Vienna's General Hospital (Alservorstadt, AKH Tom. 5, fol. 271) suggests that his livelihood had suffered a grave economic downturn. His Sperrs-Relation, issued by the Landrechte court, refers to his widow as "Wife: née Tramontini[sic], whereabouts unknown". Giacomo Tramontini's second wife Baroness Johanna Nepomuzena von und zu Aichelburg died of Lungenbrand (tuberculosis) on 2 December 1800, at Leopoldstadt 291 (today Taborstraße 26).

Maria Victoria Tramontini (Maria Labita)

After the death of her patron, Tesi Tramontini's black maid Maria Labita simply changed her name into "Maria Victoria Tramontini". All sources dating from after 1776 refer to her under this name. She moved to the house Josephstadt No. 55, "Zum grünen Rössel" (At the green Horse, today Josefsgasse 5), a move that seems to have been caused by the fact that her former colleague, Tesi Tramontini's aforesaid servant Johann Straner, lived there with his family.

Maria Tramontini's last residence, the house Josephstadt 55 (later numberings 10 and 11) on Huber's map. The Auersperg Palace is on the left (W-Waw, Sammlung Woldan).

At this house, Josephstadt 55, Maria Tramontini is listed as "Maria Tramontinier" in the 1788 municipal tax register. She lived in a small apartment on the first floor towards the street.

Maria Tramontini given as tenant at Josephstadt 55 in the Josephinische Steuerfassion (A-Wsa, Steueramt B34/25, fol. 123)

In her late years, the former maid Maria Tramontini, whom a net inheritance of 1,710 gulden had provided with sufficient means, lived the life of a well-supplied pensioner. On 18 August 1799, with the help of the paralegal Joseph Caspar Feldzug, she had her will drawn up. She was able to bequeath 500 gulden to her servant "for 13 years of faithful service". In her will, Johann Caspar Ebert turns up again, the princely steward who in 1751 had taken care of the young Carl Ditters. Maria Tramontini bequeathed 100 fl to each of Ebert's three grandsons Anton, Stephan, and Joseph. She also bequeathed 150 gulden in cash "to the truly poor and needy for the support and the better operation of their trade, profession or other enterprise", and commissioned her "trustworthy friend", the shoemaker Joseph Biedermann "to distribute the money as he may see fit". As her universal heir she appointed Biedermann's wife Regina (née Keinz) "for her thirty-eight years of service and for everything she had done for her in times of need and sickness". Since Maria Tramontini was illiterate, she signed her will with three crosses and had Joseph Feldzug write her name.

The seals and signatures on the will of Maria Victoria Tramontini (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A10, 605/1801)

Maria Victoria Tramontini, the African-born maid, died on 15 November 1801 (Wiener Zeitung, 21 Nov 1801, 4169) (the official protocol gives November 16th), at the house Josephstadt 10 (formerly numbered 55) and was buried in the old Neulerchenfeld cemetery. The entry in the municipal death register is the only source that reveals her approximate age. She had been born around 1723.

The entry in the municipal death records concerning Maria Viktoria Tramontini's (Maria Labita's) death on 16 November 1801 (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 112a, DT, fol. 45r)

Novembris 801 den 16ten

Tramontini M: Viktoria, led: Mohrin ohne Condition, Ge= / burtsort und Vaterland unbewußt, ist bein grünen Rößl, /N° 10 in der Josephstadt an Gedärmbrand beschaut / word[en] alt 77 Jr: Pirner

Tramontini Maria Viktoria, unmarried moor without profession, place of birth and home country unknown, was inspected at the Green Horse No. 10 in the Josephstadt as having died of intestinal gangrene, aged 77 years [Franz] Pirner [coroner]

In her Sperrs-Relation Maria Tramontini's profession is given as "gewesene Kammerjungfrau" (former chambermaid).

The front page of Maria Viktoria Tramontini's probate file (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 3719/1802)

The detailed study of the fate of Tesi Tramontini's African maid may seem excessive, but it has a reason. Maria Labita – renamed Maria Tramontini – was the only African woman who is documented to have been kissed by Mozart. In February 1778, during his stay in Mannheim, Mozart had surprised his father with his plans to take Aloisia Weber on a tour to Italy and make her a famous singer. Leopold Mozart was furious, and on 12 February 1778, wrote his son a letter, telling him what he thought of this "insane" plan. He referred his son to the careers of other prominent singers, what education they had received, and reminded him of his visit at Prince Saxe-Hildburghausen's palace and his meeting with Signora Tesi and her black maid. This visit had taken place on 13 October 1762 (Dokumente, 18).

Du gedenkest sie als Prima Donna nach Italien zu bringen. Sage mir, ob Du eine Prima Donna kennst, die als Prima Donna, ohne vormals schon in Deutschland öfters recitirt zu haben, das Theater in Italien betreten. Wie viele Opern hat nicht die Sgra. Bernasconi in Wien recitirt und zwar Opern in den größten Affecten und unter der genauesten Kritik und Unterweisung des Gluck und Calsabigi! Wie viele Opern sang die Mlle. Deiber in Wien unter der Unterweisung des Hasse und unter dem Unterricht der alten Sängerin und berühmtesten Actrice der Sgra. Tesi, die Du beim Prinzen Hildburghausen gesehen und als ein Kind ihre Mohrin küßtest! (Mozart, Briefe und Aufzeichnungen II, 275)

Your plan is to take her to Italy as a prima donna. Tell me, if you know of any prima donna who has ever ventured to tread the Italian stage as prima donna, without having first been before the public in Germany? How many operas did Signora Bernasconi appear in at Vienna, under the judicious superintendence and instruction of Gluck and Calzabigi? How many operas did Mdlle. Deiber sing in at Vienna, under the instruction of Hasse, and the tuition of the old singer and most famous actress, Signora Tesi, whom you saw, at the Prince Hildburghausen's, and, when you were a child, whose Moorish maid you kissed? ("Addenda to the Life of Mozart", The Musical Times and Singing-Class Circular, No. 178, 1857, 153)There is, of course, a lot of research still to be done on Tesi Tramontini's singing career and especially on her eventful married life. This small effort is only meant to serve as impetus and incentive.

The aria "Pur ch'io possa a te, ben mio" from Hasse's Marc'Antonio e Cleopatra, written in 1725 for Vittoria Tesi

Vittoria Tesi Tramontini's personal seal

Bibliography

Beicken, Suzanne J. 2004. Treatise on Vocal Performance and Ornamentation by Johann Adam Hiller. Cambridge University Press.

Bermann, Moriz. 'Eine Opernsängerin der "alten Zeit."'. Blätter für Musik, Theater und Kunst. 30 March 1858, 102.

–––––––. 1881. Maria Theresia und Kaiser Josef II. in ihrem Leben und Wirken. Vienna: A. Hartleben's Verlag.

Burney, Charles. 1773. The present state of music in Germany, the Netherlands, and United provinces. London: T. Becket and Co.

Bülow, Jakob Friedrich Joachim von. 1780. Historische, Genealogische und Critische Beschreibung des Edlen, Freyherr= und Gräflichen Geschlechts von Bülow. Neubrandenburg: Christian Gottlob Kord.

Bülow, Jakob Friedrich Joachim von. Bülow, Paul von. 1858. Familienbuch der von Bülow. Berlin: Königliche Oberhofdruckerei.

Coleridge, Arthur. 1896. The Autobiography of Karl von Dittersdorf, dictated to his son. London: Richard Bentley and Son.

Croce, Benedetto. 1891. I teatri di Napoli, secolo XV-XVIII. Napoli: Presso Luigi Pierro.

de Rossi, Giovanni Gherardo. 1786. Elogio dell'abate Giuseppe Antonio Taruffi cittadino bolognese recitato nella pubblica adunanza di Arcadia del dì 13. luglio 1786. Roma: Presso Antonio Fulgoni.

Ditters von Dittersdorf, Carl. 1801. Lebensbeschreibung. Seinem Sohne in die Feder diktiert. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel.

Fantuzzi, Giovanni. 1790. Notizie degli scrittori Bolognesi. Tomo ottavo. Bologna: Stamperia di Tommaso d'Aquino.

Godt, Irving. 2010. Marianna Martines. Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Gugitz, Gustav. 1921. Giacomo Casanova und sein Lebensroman. Vienna: Verlag Ed. Strache.

Haan, Friedrich Freiherr von. 1906. "Auszüge aus den Sperr-Relationen des n.-ö. und k. k. n.-ö. Landrechts 1762-1852". Jahrbuch der Gesellschaft Adler Bd. 16. Vienna: Selbstverlag der Gesellschaft Adler, 146-201.

Helden= Staats= und LebensGeschichte Des Allerdurchlauchtigsten, und Grosmächtigsten Fürsten und Herrn, Herrn Friedrichs des Andern Jetzt glorwürdigst regierenden Königs in Preussen, etc.. Vierter Theil. Frankfurt und Leipzig, 1759.

Hiller, Johann Adam. 1780. Anweisung zum musikalisch=zierlichen Gesange. Leipzig: Johann Friedrich Junius.

Hirtenfeld, Jaromir. 1857. Der Militär-Maria-Theresien-Orden und seine Mitglieder. Nach authentischen Quellen bearbeitet. Vienna: Staatsdruckerei.

Khevenhüller-Metsch, Johann Josef, Fürst zu. 1907. Aus der Zeit Maria Theresias. Tagebuch des Fürsten Johann Joseph Khevenhüller-Metsch. Kaiserlichen Oberhofmeisters. (Rudolf Khevenhüller-Metsch, Hanns Schlitter, eds.), 1742-1776. Leipzig/Vienna: Adolf Holzhausen.

Verzeichniß der um die k. k. Haupt- und Residenzstadt Wien befindlichen Vorstädten, Gründen, Gassen, numerirten Häuser, Innhaber und ihrer Schilder. Wien bey Joseph Anton Edlen von Trattnern. Vienna 1778.

Wißgrill, Franz Karl. 1794-95. Schauplatz des landsässigen Nieder-Oesterreichischen Adels vom Herren= und Ritterstande von dem XI. Jahrhundert an, bis auf jetzige Zeiten. Vol. 1 and 2. Vienna: Franz Seizer.

Wurzbach, Constant von. 1856-91. Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich. Vienna: Verlag der k.k. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei.

© Dr. Michael Lorenz 2016. All rights reserved.

Updated: 24 May 2025

See also: A Tesi Tramontini Addendum: Tesi's Mass Endowment Deed

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

Thank you, Dr Lorenz. That was absolutely fascinating. I have long wondered about Mme Tesi and whether the portrait Ditters painted of her was really accurate. It seemed a bit too pat for me and my impression of the composer was that he was something of a credulous "Schwaetzer" - see his anecdotes about Nicolini and Quadagni. Carl Krebs calls him a "consummate socialite who inwardly cherished life's trivialities" (my translation). Other observers of Mme Tesi were rather less starry-eyed about her than Ditters. A French source from 1773 says she had "une voix ingrate...elle fit souvent verser des larmes. C'est peut-etre la premiere actrice qui ait recite bien en chantant mal".The story about her liaison with Tramontini in what the Germans call a "Josephsehe" (marriage blanc) is also a bit suspect because another of my sources claims she squandered her fortune on a lover called Casnedi. And what was the source of her wealth if, as Ditters claimed, it amounted to 300,000 Gulden? After all, as you yourself have noted, Empress Maria Theresa paid only 400,000 Gulden to purchase Schloss Hof from Prince Eugen's niece.(Although she added enormous value to it). Incidentally, I discussed this price with the guide at Schloss Hof on a recent visit and he reckoned the Empress got an out-and-out bargain! The subsequent information you unearthed about the couple and their properties and subsequent deaths was most interesting and a tribute to your careful and painstaking work among the archives which has enriched us all. I have recently updated Coleridge's 1896 version of Ditters' memoirs, adding the bits he omitted and large parts of chapter 6 so your research has been invaluable. Vielen Dank.

ReplyDeleteThe letters attributed to Giuseppe Antonio Taruffi about Wolfgang von Kempelen's chess automaton do not exist. It is probably a case of confusion with the letters of Louis Dutens, which Meissenburg uncovered in 1978 and 1979. To my knowledge, there is no evidence that Giuseppe Antonio Taruffi was a chess player. It can be proven for his brother Giacomo, see Lolli 1763, p. 386, which I found out recently. herbertbastian@freenet.de

ReplyDelete