Ludwig van Beethoven wrote three wills. The first, the famous Heiligenstadt Testament, was written in 1802 and was found among his papers after the composer's death. Although it is (like Brahms's will) basically a letter, it meets all legal requirements of a will and would have been accepted as valid by any court of law. The second will was a letter (No. 1606 in the complete edition) written on 6 March 1823 to his lawyer Dr. Johann Baptist Bach, in which Beethoven appointed his nephew Karl sole heir and Dr. Bach curator of his estate. Quote: "Death might come without asking [...]", and "[...] you are entitled to choose a guardian for Carl with the exception of my brother Johann van Beethoven". This letter, which was once owned by Albert Cohn in Berlin and today is part of a private collection in the Netherlands, was first published by Emerich Kastner in 1910. On 3 January 1827, after Beethoven had returned sick from the countryside, he wrote a third will, also in the form of a letter to Dr. Bach (No. 2246 in the complete edition). The fourth disposition concerning his estate, bearing Beethoven's last signature, is just a short codicil, written on 23 March 1827, when the composer was lying on his deathbed and could barely write.

Only the last two wills written by Beethoven ever gained legal validity. The letter Beethoven wrote to his lawyer on 3 January 1827 (i.e. his third will) reads as follows:

Vien Mittwochs

3ten Jenner 1827

An Hr. Dr. Bach

Verehrter Freund!

Ich erkläre vor meinem Tode Karl van Beethoven meinen geliebten Neffen als meinen einzigen Universalerben von allem meinem Hab u. Gut worunter Hauptsächlich 7 Bankactien und was sich an baarem vorfinden wird – Sollten die Geseze hier Modifikationen vorschreiben, so suchen sie selbe so sehr als möglich zu seinem vortheile zu verwenden - Sie ernenne ich zu seinem Kurator, u. bitte sie mit Hofrath Breuning seinem Vormund vaterstelle bey ihm zu vertreten – Gott erhalte Sie – Tausend Dank für ihre mir bewiesene Liebe u. Freundschaft. –Ludwig van Beethoven.

m.p. [L.S.]

Esteemed friend!

Before my death I declare my beloved nephew Karl van Beethoven my sole and universal heir of all my property of which the main part are seven bank shares and what ever cash will be found. Should the law demand any modifications in this case, try to use them in his favor as much as possible – I appoint you his curator and request you to act as his father together with his guardian Hofrat Breuning – may God preserve you – a thousand thanks for the love and friendship you have shown me. –Here is the second page of this letter.

Ludwig van Beethoven.

m.p. [L.S.]

van Beethoven Ludwig Tondichter 153 [1827]

14957 Testament dd° 3t Jäner 827

publ 27t März 827

15254 Testament dd° 23t März 827

publ: 29t März 827

The Return of the Document

Mr. Johannes Othmar Müller, III., Löwengasse 7, apt. 6, today appears at the Vienna City Archive and hands over the following documents, originating from the holdings of the former civil court of the Vienna Magistrate, from the estate of his father Robert Müller, formerly residing at II., Alliertenstraße 3, apt. 8, who passed away in 1933. These documents, which once were housed in the registry of the Vienna Federal Court, were held by Mr. Robert Müller and after his death passed into the keeping of his widow Mrs. Leopoldine Müller who died on 14 August 1937. The files rightfully belong into the holdings of the Vienna City Archive, because in 1924 the archive took over the files of the civil court of the Vienna City Magistrate from the Landesgericht.

1.) An original will of Ludwig van Beethoven dated 3 January 1927 (two leaves),

2.) From the probate records of his brother Karl: 2 submissions by Ludwig van Beethoven from 28 November 1815 to the Lower Austrian Federal Court (1 leaf) and from 1 February 1818 to the Vienna City Council (6 leaves),

3.) Files from the registry of the Lower Austrian Federal Court: 1 submission by Therese Vogel, widowed Niembsch v. Strehlenau to the Federal Court from 22 June 1825 (2 leaves) and one submission, presented on 9 December 1825 (2 leaves),

4.) A protocol dated 2 June 1786 concerning the counterfeiting case Oelsner-Count Pozdazky.

Read and signed, Vienna 31 August 1937.

Dr. Mattis Arch. Dir. Johann Othmar Müller

[overleaf note]

The will of Ludwig van Beethoven listed under 1.) was added to the second will dated 23 March 1827, wills of the court of the Vienna Magistrate No. 158 ex 1827.

The files listed under 2.) were placed into the probate records of Karl van Beethoven No. 1275 ex 1819.

- Beethoven's third will, i.e. the letter he wrote to his lawyer Dr. Bach on 3 January 1827 which Müller had stolen before 1924 from the collection of wills held by the archive of the Vienna Landesgericht für Zivilrechtssachen.

- a) Beethoven's letter to the k.k. n. oe. Landrecht of 28 November 1815 (No. 857 in the complete edition of Beethoven's letters) in which he declares his will to take guardianship of his nephew according to his brother's last will. b) Beethoven's letter to the municipal Civil Court concerning his pedagogical concept regarding the education of his nephew Karl. This eleven-page letter, bearing the wrong year "1818" (it was actually written on 1 February 1819) consists of 2169 words and is the longest existing letter in Beethoven's hand (No. 1286 in the complete edition). It was originally part of the Sperrs-Relation (probate file) of Beethoven's brother Karl which in 1815 had erroneously been drawn up by the k.k. Landrechte with the shelfmark Fasz. 5-174/1815, and in 1819, was transferred to the Magistratisches Zivilgericht (the civil court of the Vienna Magistrate) under the registry number Fasz. 2-1275/1819. This long letter was first published in 1902 by Alfred Christlieb Kalischer ("Ein ungedruckter Brief Beethovens", in: Die Musik, December 1902, 403-11) who had found a copy of this letter in Otto Jahn's Beethoven estate in the Royal Library in Berlin. According to Kalischer, the first page of this copy bore the following note by Ludwig Ritter von Köchel: "Nach dem von Beethoven durchaus eigenhändig geschriebenen Originale bei dem Wiener Landesgericht" ("[copied] from Beethoven's completely autograph original at the Vienna Federal Court").

- Therese Vogel was the mother of the poet Nikolaus Lenau. Her two submissions to the Federal Court may have been related to the investigation that the Austrian police had initiated against her son, because by publishing under his pseudonym he had repeatedly circumvented the strict censorship laws.

- The protocol concerning the "counterfeiting case Oelsner-Count Pozdazky" pertains to a legal cause célèbre of the Josephinian era.

The Podstatzky-Liechtenstein Case

Count Franz Anton von Podstatzky-Liechtenstein was born on 23 November 1754 in Brno, son of Alois Ernst von Podstatzky-Liechtenstein (1723–1793), heir to the house Liechtenstein-Castelkorn and minister in charge in Bavaria. In 1786, Franz Anton von Podstatzky-Liechtenstein hoped that his noble birth would put him outside jurisdiction and shield him from prosecution. To support his expensive lifestyle he began counterfeiting Bancozettel (early Austrian banknotes). Rumors about these illegal activities reached Joseph II who summoned Podstatzky-Liechtenstein and told him in friendly, but no uncertain terms that if he continued his forgeries, he would compromise his family's reputation and bring shame upon his relatives. The Count ignored the Emperor's warning, and, with the help of a young engraver and a group of accomplices, produced 7,000 fake Bancozettel in a workshop in Nußdorf. He eventually was reported to the police by his own chamberlain Johann Elsner who had instigated the counterfeiting in the first place (on 22 April 1786, the Preßburger Zeitung claimed that Podstatzky was betrayed by a Jewish accomplice who received a reward of 10,000 gulden). In my opinion, Elsner and the engraver were one and the same person, but this remains unclear. In the first volume of his Reminiscences, the singer Michael Kelly recounts the events as follows:

The "Hantz garden" was the Augarten, "Princess L____n" was Princess Eleonore von Liechtenstein (1745–1812), a recipient of one of the few farewell letters that Joseph II wrote in 1790 shortly before his death. Similar to the embezzler Johann Cetto von Cronstorff (1729–1786), who in 1782 had been Constanze Mozart's witness at her wedding, Podstatzky-Liechtenstein was sentenced to "public forced labor" which at that time meant sweeping the streets in Vienna. This typical Josephinian punishment somehow backfired when the Count, while working in the streets, saluted a highranking figure with his broom. The Emperor had enough, and on 31 August 1786, had Podstatzky and his accomplice Elsner deported to Peterwardein and Semlin respectively, where they were forced to pull ships on the Danube.

Since very few delinquents survived this gruesome labor for more than two years, Podstatzky-Liechtenstein's punishment amounted to a death sentence. On 10 January 1787, the slavonisch-banatisches Generalkommando reported the death of twenty arrestees, among them Podstatzky-Liechtenstein. Johann Elsner's death was reported on 20 October 1787. In his card catalog pertaining to the entries in the court's cabinet protocols, the historian Gustav Gugitz describes this case as "actually a judicial murder by Joseph II".

It is not known where the documents related to Lenau and Podstatzky-Liechtenstein are today and if in 1937 the City Archive passed them on to their legal owner, the Allgemeines Verwaltungsarchiv department of the Austrian State Archives. According to a written statement, issued on 15 January 2014 by the responsible archivist Dr. Roman-Hans Gröger, "the registry of the holdings of the State Archive of Interior does not contain any reference to the searched donation". By stealing them, Robert Franz Müller saved two valuable documents from the 1927 fire of the Palace of Justice, but after their return nobody could save them from the unfathomable labyrinths of Vienna's archives.

The events at the Vienna City Archive in August 1937, when Johannes Müller came forward with four precious documents that his father had stolen before 1924, are easy to reconstruct. Müller junior must have realized that it would be difficult to sell the priceless Beethoven documents. Therefore he offered the head of the archive Dr. Richard Mattis the following deal: for returning the documents Müller requested that the whole affair and the identity of his father would be kept secret. As the case of stolen autographs in the Vienna City Library has shown, sometimes a theft is simply too embarrassing for a public institution to be fully made public. Thus, the Vienna City Archive kept its promise until long after Johannes Müller's death. The Aufnahmeschrift from 1937, which eventually led to the truth about Robert Franz Müller's thefts being revealed, was always meant to be kept confidential. The Beethoven file in Vienna's Municipal and Provincial Archives (A-Wsa, Hauptarchiv, Persönlichkeiten B16) still contains the following note, written by the archivist Hanns Jäger-Sunstenau.

B e e t h o v e n ' s will of 3 January 1927 came into the possession of the Vienna City Archive only on 31 August 1937. See the archive file with the number: 970/1937.

This note is to be kept confidential!

Robert Franz Müller

Robert Franz Müller was born on 26 June 1864 in Vienna's Leopoldstadt district (at Obere Donaustraße 41), fourth child of Eduard Bruno Müller, official of the "K:K: Central-Hofbuchhaltung" (I. & R. central accounting department) and his wife Franziska Theresia, née Schenböck (the spelling "Schönbeck" that is found in many sources is incorrect).

Müller's father Eduard Bruno Müller had been born on 4 October 1826 in Mährisch Trübau and had come to Vienna before 1851 where he is recorded as "Student" on a conscription sheet of the house Alsergrund 315. On 29 November 1855, Eduard Müller married Franziska Schenböck, born on 6 March 1831, daughter of the "K.K. Bankal-Zilleneinnehmer" (tax collector for flat-bottomed boats on the Danube) Ignatz Schenböck (b. 26 July 1800 in Engelhartszell, d. 6 November 1832 at Leopoldstadt 140) and his wife Theresia, née Summerer (b. 19 September 1805 in Erdberg, d. 24 September 1869). On 22 December 1869, Eduard Bruno Müller was appointed "K.K. Rechnungsoffizial" with the ministry of finance. Only one of his five children – Robert Franz – can be documented as having been still alive in 1890. Eduard Bruno Müller died of pneumonia on 29 January 1905 in his home at Nordbahnstraße 8. When in 1962 Leopold Nowak bought Robert Franz Müller's estate (A-Wn, F56 Müller) for the music collection of the Austrian National Library, Müller's son Johannes Othmar Müller provided a "Kurze biographische Skizze" ("short biographical sketch") about the life of his father (A-Wn, F56 Müller 1). This document claims that Robert Franz Müller was related to the composer Wenzel Müller – a claim that could not be verified – and that his mother had been a sister of the DDSG captain Josef Poscher (b. 29 April 1839), a close friend of the conductor Hans Richter. Müller was very proud of his relationship to Josef Poscher, but, as a matter of fact, Poscher was not Franziska Schenböck's brother, but her half-brother and the original name of Josef Poscher's father was not really Poscher, but Fitzel.

Robert Franz Müller enjoyed an excellent musical education. After having studied violin with Josef Hellmesberger and counterpoint with Anton Bruckner, he had to renounce an artistic career for financial reasons and entered civil service in the Austrian postal administration. Müller pursued his musical activities in his free time: he composed songs and waltzes and was the musical leader of two choral societies. His other main interest outside his job was historical and musicological research in Vienna's archives, the results of which he published in various Viennese newspapers. After his retirement on 1 November 1922 (after 489 months of service), he fully concentrated on Beethoven research. According to his son, his most important work was a lengthy article titled "Beethoven's Relatives" whose significance is based on the fact that some of the material that Müller was able to use was to perish in the 1927 fire of the Palace of Justice. For instance, Müller's research concerning Beethoven's sister-in-law (now A-Wn, F56 Müller 27) was still used by Sieghard Brandenburg in his article entitled "Johanna van Beethoven's Embezzlement" (in: Essays in Honor of Alan Tyson, Oxford 1998). O. E. Deutsch used some of Müller's material on Schubert's uncle Karl without naming his source. Müller's archival research on various topics of Viennese music history and its pioneering quality made him an internationally sought after authority in regard of biographical data of friends and relatives of composers and musicians. Müller regularly corresponded with prominent musicologists and historians. When Theodor Frimmel was preparing the publication of his 1926 Beethoven-Handbuch, he asked Müller for information. Frimmel's frail health and bad eyesight were the causes of many mistakes in the Beethoven-Handbuch. On 18 November 1926, Frimmel wrote the following resigning words to Müller:

Der frühere Trost des Klavierspiels oder sogar des Patience–legens verfängt nicht mehr –– Nur der grosse Hund wird immer deutlicher, der mir auf's Grab sch––– wird.

The earlier comfort of playing piano or even playing solitaire has no effect anymore –– Only the big dog is becoming increasingly recognizable which will poop on my grave. (A-Wn, F56 Müller 6)

The historian Arthur Schurig (1870–1929), who in 1927 was working on a (never to be published) Chronologie zu Beethovens Leben und Schaffen, also corresponded with Müller for whom he had nothing but praise, while he harshly criticised most of his colleagues: "The gaps in the so-called detail work of biographical material are enormous. Basically nothing has been done since Thayer. [...] Of course, Frimmel just ruminates the old and well-known cabbage. And in what apothecary German! [...] The Beethoven-Year has produced absolutely nothing so far, because Orel, Frimmel, Nohl, and Kobald present nothing new." (Schurig to Müller on 19 February 1927, A-Wn, F56 Müller 18).

Müller's research and publications included the following selected topics:

- Beethoven's friends and contemporaries

- Beethoven's burial

- Johanna van Beethoven's crimes

- Beethoven's family (from files of the Vienna police)

- An unknown apartment of Beethoven in Altlerchenfeld

- Mozart in Upper Austria

- Emanuel Schikaneder

- Schubert's relatives

- Schubert's body height

- Therese Grob

- Haydn's will (first publication)

- Marriage contract, will and probate documents of Haydn's wife (first publication)

- Hans Richter's "Pilot" (a Great Dane that Richter bought from Josef Poscher)

- Josef Lanner's mistress Marie Kraus

- Ferdinand Raimund

- Franz von Suppé

From Müller's correspondence we know that he owned a significant and widely admired "Autographensammlung" (collection of autographs) and we have a strong hunch concerning the possible way this collection was put together. Müller might have arranged the fate of these documents and their distribution after his death in a detailed will, but he seems never to have considered this an important issue. A sudden death forestalled all possible provisions. On 15 February 1933, while waiting in line at the post office at Weintraubengasse 22, Müller suffered a massive stroke and died (as the newspapers put it) "within a few moments".

Müller was survived by his wife Leopoldine (née Weber), living at Alliertenstraße 3/8 and his son Johannes, "39 J., Privatangestellter, Wien III, Löwengasse 7/6". Not surprisingly, the existence of the autograph collection does not appear in Müller's short probate document which under "assets" merely states "kein Nachlaß" (no estate).

Right after her husband's death, Müller's widow may have sold off certain items from the autograph collection which would explain the fact that some documents from Karl van Beethoven's Sperrs-Relation were not returned in 1937 by Müller's son, but ended up in other places. As long as his mother was alive, Johannes Müller did not want, or was not allowed to return the Beethoven documents, because Leopoldine Müller obviously did not want to tarnish her own and her husband's reputation. Leopoldine Müller died on 14 August 1937. She left a will in which she possibly addressed the issue of the autographs, but this document is not accessible, because the particular box from the holdings of the Leopoldstadt district court could not be found in Vienna's Municipal and Provincial Archives. Only after his mother's death, did Johannes Müller dare to come forward with the valuable Beethoven material and for doing that posterity owes him gratitude. It is not known what became of the main part of Robert Franz Müller's collection. Johannes Othmar Müller died childless on 18 August 1965, his widow Aloisia Maria Müller (b. 1894) died in May 1986. In 1965 the plaque on the stone of the family grave was replaced and now bears only Johannes Müller's name.

The following people are buried in this grave:

Eduard Müller (1826–1905, Robert Franz Müller's father)Aloisia Müller was the last surviving family member. The grave fees were only paid for ten years and the right to use this burial site expired on 27 May 1996.

Franz Müller (1831–1901, Robert Franz's uncle)

Robert Franz Müller (1864–1933)

Leopoldine Müller (1867–1937, Robert Franz's wife)

Therese Schenböck (1832–1902, Robert Franz Müller's aunt)

Johannes Othmar Müller (1893–1965, Robert Franz Müller's son)

Aloisia Maria Müller (1894–1986, Johannes Othmar Müller's wife)

Robert Franz Müller's work was generally excellent and far more meticulous than that of his contemporaries which – as we know only now – was based on the fact that he sometimes had the archival sources he used at home on his desk. It turns out that some stolen items, which once were part of Müller's collection, survive and their provenance can be traced.

Other Thefts by Müller

The Paganini file

Müller's article was based on one single file from the "Faszikel 3" series of the civil court of the Vienna City Magistrate, which, among other issues, covers custody cases. This file (bearing the original shelfmark Mag. ZG, Fasz. 3 - 688/1828) is now missing from the holdings of the Vienna Municipal Archives.

The Strauss file

On 10 January 1926, the Neues Wiener Journal published an article by Müller entitled "Die Heirat des alten Strauß" in which Müller dealt with Johann Strauss, the Elder's wedding. Since he quoted documents that were part of a regular application to the Vienna Magistrate for an "Ehekonsens" (marital consent), it is obvious that Müller stole the "Ehekonsens" file from the archive of the Vienna Federal Court.

When in April 1825 Johann Strauss's girlfriend Anna Streim realized that she was pregnant, the couple was a little pressed for time to get married. Since Strauss was still a minor (the age of legal majority was 24 back then), his guardian, the tailor Anton Müller, had to apply to the Vienna municipal court for his ward to be allowed to get married. The bride, who, born in August 1801, also was still a minor, got the permission from her father. On 5 April 1825, Anton Müller submitted the application, which referred to an upcoming tour of the groom. (Urgent travel plans, or the telling term periculum in mora, were widely used excuses for quick wedding preparations). Curiously, Strauss's guardian gave a wrong date of birth of the bride and pointed out the fact that, based on his income as music teacher and his concerts with the brothers Scholl, Strauss was able to earn 400 gulden per year. In addition to that, the bride was able to make money with her needlework and had a secure shelter at her parents' home during the absence of her future husband. Because Strauss was unable to attend the first hearing, scheduled for 13 May, the court extended the deadline and granted the permission on 24 June 1825. The wedding took place on 11 July 1825 (Lichtental, Tom. 10, fol. 209) in the Lichtental Church, the couple's first child was born on 25 October of that year.

Die bei der Pfarre hinterlegten Dokumente fehlen dort aus der Reihe. Sie sind von einem skrupellosen Sammler entwendet worden, wie er es auch an vielen anderen Archivstellen praktizierte. So müssen wir ihm noch dankbar sein, daß er wenigstens manche urkundlichen Texte in der Tagespresse veröffentlichte. (Jäger-Sunstenau, Johann Strauss 1965, p. 20)

The documents that were deposited at the parish are missing from the series there. They were stolen by an unscrupulous collector, as he practiced it at many other places in archives. Thus, we even have to be grateful to him that he published at least some documentary texts in the daily press.

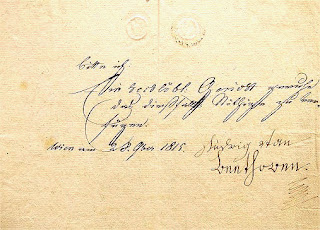

A document from Karl van Beethoven's probate documents, stolen by Robert Franz Müller before 1924, which Müller's relatives were obviously unable to sell, ended up in Müller's estate in the Austrian National Library (A-Wn, F56 Müller 93). It is a letter by Cajetan Giannattasio del Rio (1764–1828), the owner of the boarding school that Beethoven's nephew Karl attended, to Beethoven's sister-in-law Johanna who had fought with the composer in court over her son's guardianship. That the letter once belonged to the file of the civil court is proved by the imprinted six kreuzer revenue and the control stamp on top of it. Del Rio was ordered by the court to write this letter and he submitted a copy of the document as evidence.

6 Xr.

Frau v. Beethoven.

I have to notify you herewith that you will never again be allowed to visit your son in my institution, and that is because of an order which I myself considered necessary and which was stipulated by the guardian. On the basis of the resolution issued by the Landrechte court to the uncle and guardian respectively, of which I hold the original in my hands, it is absolutely within his authority to decide, whether, how and where you can see your son. Regarding this issue you must consult only with him. I request you therefore not to come into my house again, because you would be faced with the most unpleasant scenes.

8. März 816 Giannattasio Edl: del Rio mpia

A letter by Karl von Valmagini

A second historical document in Müller's estate in the ONB, which must once have been part of his autograph collection, is a letter by the military officer Karl von Valmagini, dated Bucharest, September 27th, 1790, to his aunt in Vienna (A-Wn, F56 Müller 94). Valmagini's aunt was nobody else than Maria Anna von Gluck, widow of Christoph Willibald Ritter von Gluck. On 22 December 1740, Valmagini's father, the Milan Mauro Ignazio von Valmagini, had married Maria Josepha Bergin who was Gluck's future sister-in-law. In 1790, Karl von Valmagini took part in the Austro-Turkish War and the request he had from his wealthy aunt was a simple and obvious one: he asked her if she would be so kind as to lend him an amount of 500 to 1,000 ducats. How Valmagini's letter came into Müller's possession is not known. The document is an interesting Gluck family item, but its financial value is neglible.

The 1982 Hassfurther Affair

In January 1982 the Viennese auction house Hassfurther offered a Beethoven document for sale at a price of 50,000 Schillings (then about $5,070). It was a two-leaf sheet of paper with one and a half pages of handwritten text bearing the composer's autograph signature. The document's text consists of a protocol of a meeting which took place on 29 March 1820 at the civil court of the Vienna Magistrate in the presence of the following people who discussed issues regarding the custody of Beethoven's nephew: the Vienna City councilors Franz Xaver Piuk, Aloys Beranek and Anton Bayer; the court recorder Leopold Staudinger, Ludwig van Beethoven and the writer Joseph Carl Bernard. According to the protocol, Beethoven stated that "first, he persists to request the guardianship [of his nephew] in accordance with his brother's will and the law, second, that he proposes Herr von Peters, Court councilor of Count Lobkowitz as co-guardian, third, he requests that Johanna van Beethoven be excluded from the guardianship like it was decreed earlier by the Landrechte court; and, fourth, referring to the statements he already made earlier to the civil senate, that he is fully taking care of his nephew and that he accepts a co-guardian, but certainly not a guardian, because he persists on his right of guardianship and that based on his experience he is sure that no other guardian is able to take care of the ward the way he can".

Dear ladies and gentlemen,

some time ago the Municipal and Provincial Archives of Vienna came into the possession of a xerox of a document that you are offering for sale. The document in question, which bears Ludwig van Beethoven's signature, is a sheet from the probate records of Karl van Beethoven, the composer's nephew[sic]. Because these probate records – like Beethoven's and those many other prominent people – are held by the Provincial Archives and because it can be presumed that the document has been removed in the past from the original file, we would very be very interested in clarifying the situation. Therefore we would like to ask you for a talk concerning this matter and would be grateful for an appointment.

Respectfully yours [...]

On 31 March, I visited the Gallerie Hassfurther to conduct a conversation concerning a document that bears the original signature of Ludwig van Beethoven. This document, which has been offered for sale by the above gallery, originates from the probate records of Karl van Beethoven. [...] Our former colleague Dr. Hans Jäger-Sunstenau pointed the attention of the archive to the aforesaid document which is being sold by Hassfurther. After the archive had asked for an appointment weeks ago without getting any reaction, a personal visit to the gallery seemed necessary. When I requested information concerning this matter, I was told in a harsh and dismissive manner by the head of the gallery that the archive had absolutely no right to request information, even less to make a claim on the document proper. He told me that the sheet in question had already been taken from the holdings of the court between 1850 and 1870 and that the gallery had received this information from an unnamed scholar. Apart from that, the gallery refuses to provide any further information and all future conversations have to be conducted with the Viennese lawyer Dr. Rudolf Bazil.

(A-Wsa, Hauptarchiv, Persönlichkeiten, B14)

Epilogue

The popularity that Beethoven material enjoys with ruthless thieves has a long tradition in Vienna. Beethoven is the only major composer, whose entry in the official death register of the Vienna City Council has been cut out about a century ago. When in 1922 the volume in question was transferred to the City Archives, the official in charge considered it necessary to glue the following "Amtsvermerk" (official note) to the cover page:

At the letter BP folio 23, containing the death date of the composer Ludwig van Beethoven (+ 26/3 1827), is missing. In the report of the journal of the Toten-Amt ["TAZ"], which was submitted today by this office to the Archive of the City of Vienna, this was especially empasized. Conscription office, department for burial issues, on 13 Februry 1922. Max Kamp senior supervisor, head of the Toten-Amt

The missing leaf in the death register with Beethoven's name has been replaced with a typescript copy of the death notices in the Wiener Zeitung of 30 March 1827.

We find ourselves wondering how Mozart's and Schubert's entries in Vienna's death registers ever could survive into the twenty-first century.

Until 1924, Beethoven documents in the archives of the Vienna Federal Court were plundered ruthlessly, and we can safely state that every document in the collection of the Beethoven-Haus that bears an Austrian imprinted revenue stamp once belonged to these archives. Unfortunately, the losses of valuable material have not ceased: in 1969 Hanns Jäger-Sunstenau numbered the leaves of the Beethoven file in the Vienna City Archive with a ballpen, but in 1999 I discovered that nine of them had already been stolen.

Owing to the lack of a reliable inventory (Jäger-Sunstenau's documentation from 1970 is very fragmentary), the archive could not even figure out what exactly had gone missing. When in 1999 I informed the (meanwhile retired) head of the archive Ferdinand Opll of the loss, he bluntly replied: "We have so many files of prominent people!"

© Dr. Michael Lorenz 2014. All rights reserved.

Updated: 19 April 2023

The second paragraph addresses Frau Müller's four creditors whose demands are supposed to be covered by the life insurance for civil servants. An eventual surplus from this insurance was supposed to go to Hans Müller. The will was written on 30 July 1937. The three witnesses, Margarete Wojak, and the police officer Jakob Lackenbucher and his wife, were neighbours of Frau Müller at the house Alliiertenstraße 3 (Adolph Lehmann's allgemeiner Wohnungs-Anzeiger 1937, vol. I, p. 712 and 1472). It seems that Robert Franz Müller's autograph collection was either silently passed into the ownership of his son already in 1933, or – with the exception of the four documents decribed above – it was sold in 1937.

In September 2019, I was able to unearth the documents from Robert Franz Müller's family that did not end up in the Austrian National Library. This material contains a number of interesting photographs, and reveals yet another theft perpetrated by Müller. Details will follow.

© Dr. Michael Lorenz 2020. All rights reserved.

.jpg)

Excellent work, and very entertaining.

ReplyDeleteMany thanks for your scrupulous investigations!

ReplyDelete