In her will, written on 23 June 1841, Constanze Nissen bequeathed a pearl necklace to her sons with the following words: "11 Schnüre gute Perlen mit Elfenbein-Schließe, von dem berühmten

Hesse in Brillanten gefaßt"("11 strings of good pearls with an ivory clasp by the famous

Hesse edged in diamonds"). A miniature portrait of Constanze Nissen, allegedly by Thomas Spitzer shows her wearing the pearl necklace in question.

According to the Mozarteum, this portrait was done in 1826, but Johann Evangelist Engl's attribution of this miniature is false. Since Thomas Spitzer already died on 15 August 1821, the portrait must be a work of Franz Spitzer (Julius Leisching: "Die Bildnis-Miniaturen des Salzburger Museums",

Salzburger Wacht, Nr. 39, 15).

In early 2010,

Günther G. Bauer published a book entitled

Mozart. Geld, Ruhm und Ehre, in which he claimed to shed light on Mozart's finances. Bauer's book was one of the worst Mozart books in recent years and a true example of what today's fake Mozart scholarship can lead to. Bauer presented an endless heap of pointless speculation on Mozart's expenses that had no basis in archival research and no connection whatsoever with primary sources. One of the worst flaws of Bauer's book was the fact that he naively took his data on Mozart's income from Maynard Solomon's Mozart biography, not realizing that Solomon's numbers themselves were the result of ill-informed presumptions and flawed estimates. Bauer's book was basically a huge waste of money which Bauer mistook for a pathbreaking study in cultural history. The most entertaining parts in Bauer's opus were definitely the ones where he tried to apply his imaginary research skills to deal with special issues of Mozart's finances. In the chapter titled "Goldene Uhren, Schmuck und Tabatieren" ("Gold Watches, Jewelry and Tobacco Boxes") Bauer claimed to have identified the jeweler who made Constanze Mozart's pearl necklace and its valuable clasp. His line of argument was absolutely priceless.

In one of his legendary begging letters to

Michael von Puchberg Mozart refers to a "Galanteriewarenhändler" (owner of a fancy store) located at the

Stock im Eisen, whom he owed 100 gulden. Bauer arbitrarily identified this merchant as Johann Georg Haas who ran a "Galanteriewarenhandlung" named "

Zum König von Ungarn" in the house No. 1093 (from 1795 until 1821, No. 1159) on the Graben opposite St. Stephen's Cathedral. Bauer located an interesting list of goods that were available at Haas's shop.

Curiously, Bauer turns the name Haas into "Häas", an error which was obviously caused by two scratches above the first "a" in Haas's name on the printing plate of the above list.

Of course, the name of this tradesman was Haas (

Allgemeiner Wiener-Handelsstands-Kalender für das Jahr 1791). The name "Häas" does not exist, except in Bauer's imagination. All the primary sources, related to the merchant Johann Georg Haas (1754–1826) in Vienna's archives, are absolutely clear concerning this issue.

Johann Georg Haas's signature on his 1780 marriage contract (A-Wsa, Merkantilgericht, Fasz. 3, 1. Reihe, H 61)

It turns out, however, that Bauer desperately needed the hallucinated umlaut in "Häas" to establish a connection between Constanze Mozart's pearl necklace, Mozart's debt, and Johann Georg Haas. Based on his willful renaming, Bauer identified the "famous Hesse", whom Constanze Mozart mentions in her will, as the Viennese "Galanteriewarenhändler" Johann Georg Haas, whom, for the sake of this tormented identification, he had to call "Häas". And yet, whoever knows even a little bit about jewelry and ivory sculpture in the eighteenth century, realizes immediately that the "famous Hesse" can only refer to the really famous Sebastian Heß (1733–1800), or his younger brother Paul Heß (1744–1798). Because of their miniature ivory sculptures, carved with inexplicable mastery, set on a blue background, and covered with rock crystal glass, these two engravers (as they modestly called themselves) have become truly legendary figures in the history of art. The Viennese Galanteriewarenhändler Johann Georg Haas (who was not a regular jeweler and therefore was not allowed to sell pearl necklaces) has no provable connection with Constanze Mozart's pearl necklace.

Owing to the fact that Viennese art historians are even less competent in doing biographical research than their local musicologist colleagues, very little is known about Sebastian and Paul Heß. The only author, who has recently published on the Heß brothers, is the Austrian art historian Peter Hartmann who, however, does not even know when exactly those two artists died. Therefore I decided to shed more light on the two brothers from Bamberg who produced some of the most amazing specimens of ivory micro-carving known today. To realize the very special kind of art we are dealing with, when we speak of the wonders the Heß brothers produced, we have to take a look at Sebastian Heß's so-called "Maria-Theresia Brooch" which took the artist three years to make.

This unique piece of jewelry, whose value at a 2002 auction was estimated at 375,000 €, is only seven centimeters wide. The three river miniature landscapes contain 26 figurines, five houses, five trees, and two ships (of which one is only one milimeter high). The blue background is made of pulverized cobalt, applied inside the silver cases that hold the sculptures.

Sebastian Heß: Centerpiece of the Maria-Theresia Brooch (2,4 x 1,7 cm)

The fishing rod of the fisherman on this centerpiece of the brooch is about 0,02 mm thick. How Sebastian Heß managed to carve the branches of the trees without ever tilting the file or breaking a branch, is a total mystery. The problem is not only the cutting and filing of the piece of ivory, it is also the extremely difficult task of mechanically stabilizing it in such a way that prevents it from breaking while being worked on. The carvings of Paul Heß (no Viennese source ever calls him Paul Johann) excel in similar dazzling micro-artistry. The exquisitely lifelike shape of his trees is even more intricate, and thus, quite distinguishable from his brother's work. The size of the following landscape with a classical facade (with the signature

HESS) is 3,2 x 2,7 cm.

Paul Heß: Landscape with Classical Facade

Both of the above pieces of jewelry were given by Maria Theresia to her personal physician

Jan Ingenhousz for rescuing her family from smallpox. In 1779, after his return to England, Ingenhousz sold them for a fortune and until their sale in December 2002, they were part of the so-called

Connoisseur Collection that consisted of 29 micro carvings. In 1782, the German historian

Johann Georg Meusel (1743–1820), who was personally acquainted with the Heß brothers, described their work in his addenda to Füeßli's Lexicon

Miscellaneen artistischen Inhalts as follows.

The brothers Heß, born in Bamberg; for a long time they lived in Brussels, where especially the elder stood in high regard with the late Prince Charles of Lorraine whom he had to assist in the Prince's various hobbies. Since several years both brothers have settled in Vienna where they still reside. The actual object of their art consists of ivory, whereof especially the younger delivers pieces of incomprehensible smallness and delicacy; by then (1780) he was working on a box lid for the Russian Empress that shows a rural landscape with trees, a farmhouse, and a view on the water where one could see people, cattle and everything arranged and executed so splendidly that the incomprehensibly small is in no way inferior to the greatest in art. He also makes bracelets of this kind for ladies and rings for both sexes that currently are so very popular in Vienna that only few ladies and gentlemen don't wear them. Heß makes his trees and figures through a magnifying glass piece by piece and then pins them with glue into the ivory bottom one after the other. The background is always blue to make the beauty of his wooly incomparable trees even more discernible. His forgrounds he usually decorates with a bridge, Roman ruins or a country house. At the same time he knows how to set everything properly into action; at one place he engages a countrywoman in feeding her fowl and you see the oats fall from her hands: elsewhere a young man is standing in a tree, throwing an apple into the apron of a girl and you can actually see the apple's stem in his hand: at a third place a woman is drawing water from a well and in her hands one can see the ivory rope going across a wheel: here and there he puts a recumbent sheperd with his cattle, or assigns some other rural activity to his figures. [...] Heß is a completely singular genius and an enthusiast of this art which he is able to judge with deep understanding. The easiness of his work is incredible; I have been watching him many times for hours with amazement, how he produces one creature after the other with his delicate saw; one thinks to be able to imitate the man's work, only to finally leave him, indignant about the fact that nobody can learn anything from this man who certainly has no peer.

Paul Heß: Maid at the Well (1,4 x 1,2 cm!)

Paul Heß: Pastoral Scene at the Foot of a Rock (clasp of a necklace, 3,2 x 2,7 cm)

Paul Heß: Pastoral Scene at the Foot of a Rock (clasp of a necklace, 3,2 x 2,7 cm)

Archival research shows that during the last quarter of the eighteenth century, actually four Heß brothers lived in Vienna.

1) Johann

Theodor Heß was born on 30 November 1730, on the Kaulberg in Bamberg, and was baptized on the following day in the

Obere Pfarre (

Unsere Liebe Frau, M8/21, 219).

He was the first child of the master locksmith Philipp Jacob Heß (Höss) from

Bebenhausen in Swabia, who, on 20 February 1730, had married Maria Margaretha Flensberger, daughter of the Bamberg court assessor Bernhard Flensberger (

Bamberg, Unsere Liebe Frau, M16/43, fol. 261r).

The entry concerning Johann Theodor Heß's baptism on 1 December 1730, in Bamberg's Obere Pfarre (Bamberg, Unsere Liebe Frau, M8/21, 219)

Theodor was the first of the Heß brothers who moved to Vienna. At the occasion of his wedding on 14 August 1768 to Maria Magdalena Kreyl, he declared to have come to Vienna already in 1764.

The entry concerning Theodor Heß's wedding on 14 August 1768 in Vienna's Schottenkirche (A-Ws, Tom. 32, fol. 188v)

Theodor Heß's best man in 1768 was his younger brother Conrad's father-in-law Joseph Gissinger. From 1768 (or even earlier) until his death, Theodor Heß always lived in the house "Zum weißen Schlüssel" (The White Key) No. 363 on the Tiefer Graben (today Tiefer Graben 13).

The house Tiefer Graben 363. Puthon's house Am Hof 309 is on the left (W-Waw, Sammlung Woldan).

With his first wife, Heß had one daughter and three sons, all of whom had Johann Baptist Puthon and his mother Eva Barbara Schuller as prominent godparents. Puthon (1745–1816), who at that time, was still addressed as "Wechsler" (banker), was soon to become one of the wealthiest factory owners and merchants of the Austrian monarchy. Heß must have made the banker's acquaintance at the house of his first father-in-law Franz Kreyl who ran an inn in Puthon's house at Stadt No. 309 "

Zur großen Weintraube" (The Large Grape, today

Am Hof 7, the place of birth of the painter Joseph Mathias Grassi). After the death of his first wife, Theodor Heß married again in 1782 (A-Ws, Tom. 35, fol. 150r). His second wife was Elisabeth Schubert, daughter of Albert Schubert, a carpenter at the Schottenhof. She bore Heß two more daughters (1783 and 1789). Theodor Heß, "K.K. Hof und bürgerlicher Schlossermeister" died on 5 December 1798, of "Harnblasen" (some urologic problem).

The left half of the entry in the Schotten death register concerning Theodor Heß's death on 5 December 1798 (A-Ws, Tom. 15, fol. 87)

2) Johann

Sebastian Heß was born on 14 April 1733, in Bamberg (

Unsere Liebe Frau, M8/21, 284).

The entry concerning Johann Sebastian Heß's baptism on 14 April 1733 in Bamberg's Obere Pfarre (Bamberg, Unsere Liebe Frau, M8/21, 284). The child's godfather was the butcher Sebastian Oberreuter.

Like his father and his brothers Sebastian Heß became a locksmith. This profession seems to have been essential for the micro-sculpturing craftsmanship of the Heß brothers, because many of the inexplicable mysteries of their art were obviously based on various self-invented and specially handcrafted metal tools. In the second volume of his encyclopedia

Das gelehrte Oesterreich, Ignaz de Luca expressedly refers to Heß's initial profession.

The sources suggest that Sebastian Heß and his brothers already came to Vienna before 1770. By 1773, Sebastian was definitely active there, since in that year he started to work on his brooch for the Empress which he finished in 1775.

In 1790, Sebastian Heß published a book titled

Geschichte des alten Roms in Medaillen von Johann Dassier und Sohn (gedruckt bey Fr. Ant. Schrämbl. k. k. privileg. Buchdrucker und Buchhändler) in which he calls himself "engraver and mechanic at the late Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine". In Vienna the brothers Sebastian and Paul lived together in the house Stadt 116 on the

Schottenbastei (today

Helferstorferstraße 1) which is documented by the church records of the Schotten parish and Ignaz de Luca's 1787 handbook

Wiens gegenwärtiger Zustand unter Josephs Regierung.

Sebastian Heß also produced medals and cast copies of his own micro-sculptures which he made of a special alabaster-like substance and sold for seven Kreuzer apiece (

Wiener Zeitung 1792, 1862). Before 1798, a major strife seems to have occurred between the brothers, because on 23 March 1799, almost a year after the death of his younger brother, Sebastian Heß published an ad in the

Wiener Zeitung, in which he completely denied the artistic activity of his brother Paul and denounced him as mere distributor of his own ivory artworks (a claim that is of course refuted by J. G. Meusel's account and other testimonies).

Dem verehrungswürdigsten Publikum den irrigen Wahn zu benehmen, daß mein nicht mehr lebender Bruder Paul Heß, der wahre Künstler in Graveur=Arbeiten aus Elfenbein gewesen wäre, fordert mich auf, hiermit öffentlich bekannt zu machen, daß ich diesem, nur den Verkehr meiner Arbeiten, in Rücksicht seiner Familie, übertragen hatte, zugleich aber auch anzuzeigen, daß von nun an bey mir selbst Bestellungen auf alle Gattungen von Graveur=Arbeiten aus Elfenbein, als: Figuren, Blumen, Opfer, Namen, kleine Landschaften u.s.w. für Kabinetstücke, Schliessen, Medaillons, Dosen und Ringe können gemacht werden.

Notice.

To relieve the honorable public of the mistaken illusion that my deceased brother was the true artist of the ivory engravings, I see myself obliged to publicly declare that, out of consideration for his family, I had merely assigned him with the distribution of my work. At the same time, I herewith announce that from now on, orders can be made with me personally for all kind of engravings from ivory, i.e. figures, flowers, votiv pictures, names, small landscapes etc. for cabinet pieces, clasps, medallions, boxes, and rings.

Sebastian's wife Anna Heß ("Kunst

=Graveurs Ehegattin") died on 5 February 1786, of uterine cancer, at the age of 55 in the so-called

Tischlerherberg, Stadt 1344 (The Carpenters' Hostel, today

Ballgasse 8). In the 1788 municipal tax register Sebastian Heß is still listed as tenant of a three-room apartment on the fourth floor of this building.

Sebastian Heß listed as tenant at Stadt 1344 in the 1788 Josephinische Steuerfassion (A-Wsa, Steueramt B34/5, fol. 372v)

Sebastian Heß had two children: Elisabeth, born in Brussels in 1767, and Franz, born in 1769, who at the time of his mother's death, served as artillerist in the Austrian army in

Kaiserebersdorf Castle. When Sebastian Heß died on 13 December 1800, of dyspnea ("an Dampf") in the house Jägergasse 20 on the Laimgrube (today

Papagenogasse 4), both his children were already dead.

The outside of the cover sheet of Sebastian Heß's Sperrs-Relation (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 4594/1800)

Heß's belongings were auctioned off for net 255 fl 28 x, but at the gathering of the creditors on 26 March 1801, it turned out that the debts of the deceased amounted to 1533 fl 27 x. The meager assets were used to cover the remaining rent, the physician's fee, and the burial expenses. Not surprisingly, Sebastian's younger brother Conrad Heß renounced the inheritance.

Sebastian Heß (A-Wn, PORT_00115962_01)

The entry concerning Johann Conrad Heß's baptism on 21 September 1738 in Bamberg's Obere Pfarre (Bamberg, Unsere Liebe Frau, M9/24, 59)

Conrad also became a locksmith and moved to Vienna. His first marriage on 10 May 1767, to Eleonora Gissinger (b. 1744, daughter of the Viennese locksmith Joseph Gissinger) at St. Stephen's is the second earliest documentary evidence of a Heß sibling's actual presence in Vienna.

The entry concerning Conrad Heß's marriage to Eleonora Gissinger on 10 May 1767 (A-Wd, Tom. 64, fol. 9v)

After the death of his first wife on

23 December 1770, Conrad Heß, on 27 January 1771, married a certain Anna Maria Hallmann, a farmer's daughter from

Untergrub in Lower Austria.

The entry concerning Conrad Heß's second wedding on 27 January 1771 (St. Ulrich, Tom. 27, fol. 66v)

It seems likely that his brothers and his half-sister Johanna Heß came to Vienna around the year 1770. On 12 May 1786, Conrad Heß's success in his profession enabled him to purchase the house Stadt 640 (today

Rotgasse 9) which on 2 October 1807, he sold again for 10,500 gulden to the merchant Bernhard von Grandin. Conrad Heß and his second wife, who died on 28 March 1808 (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 2261/1808), had no children. He died on 31 January 1809 (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 2151/1809), in the house Stadt 756 (today

Fleischmarkt 11) and in his will bequeathed 12,733 gulden to his half-sister Johanna and the two children of his younger brother Paul.

The will of Conrad Heß which he signed on 30 January 1809 (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A10, 67/1809)

The main part of Conrad Heß's estate, however, consisted of a debt certificate from the buyer of his house which two years later was to lose significantly in value.

Conrad Hess's seal and signature from his and his wife's joint will which they signed on 15 January 1796 (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A10, 210/1808)

4) Johann

Paul Heß was born in Bamberg on 13 February 1744, and baptized in the church of

St. Martin (

St. Martin, M7/18, fol. 120r).

The entry concerning Johann Paul Heß's baptism on 13 February 1744 in Bamberg's church of St. Martin (Bamberg, St. Martin M7/18, fol. 120r)

Like his brothers, Paul Heß seems at first to have taken up the profession of a locksmith. His marriage to Katharina Dobler, daughter of an employee of

Archduchess Maria Elisabeth of Austria (1680–1741), took place in Brussels. He had several children of whom only two reached adulthood.

Paul Heß listed in the 1788 Steuerfassion as tenant of an apartment on the 4th floor of the house Stadt 116 (A-Wsa, Steueramt B34/1, fol. 150v)

Paul Heß did not only dedicate himself to ivory carving, but also made a number of technical inventions. In 1791, he unsuccessfully tried to establish a production of self designed "English buckles" and in 1795, in Vienna's

Prater, he presented a newly invented telegraph ("eine von ihm ganz neu erfundene, noch nie gesehene beleuchtete Fernschreibmaschine") (

Kurfürstlich gnädigst privilegirte Münchner-Zeitung, 1795, 990) that used colored light signals to communicate information. In November 1795, he also demonstrated his telegraph in the

k.k. Reitschule for an entrance fee of ten to 30 Kreuzer. In order to be able to become a member of the Viennese

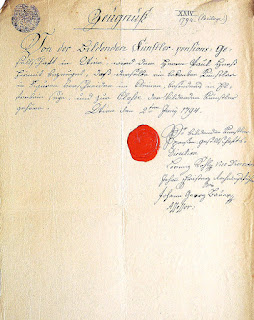

K.K. Pensionsverein bildender Künstler (the I. & R. pension society of visual artists), he needed to apply to the Empress herself, presenting a certificate of his entitlement. On 2 June 1794, Lorenz Kohl,

K.K. Hofzeichenmeister and vice director of the society, duly obliged and wrote the following:

Von der Bildenden Künstler=pensions=Gesellschaft in Wien, wird dem Herrn Paul Heeß hiemit bezeuget, daß derselbe ein bekanter Künstler in Figuren verschneiden im kleinen, besonders in Elfenbein seÿe und zur Classe der bildenden Künstler gehöre.

It is herewith certified by the Pension Society of Visual Artists in Vienna that Paul Heß is a well-known artist in carving small figures, especially of ivory and that he belongs to the class of visual artists.

Lorenz Kohl's testimony for Paul Heß written on 2 June 1794 (A-Wsa, Private Institutionen, Pensionsgesellschaft bildender Künstler, A1/1)

On 5 July 1794, Paul Heß submitted a detailed application to

Empress Marie Therese in which he explained the main reason for his dire financial situation:

Ist Endesgefertigten durch die unglücklichen Revolutionen und den so langwierigen Krieg, sein Nahrungszweig, welcher meistens im Auslande durch Versendung seiner kleinen Elfenbeinarbeit guten Fortgang hatte, gänzlich, dergestalt zurückgesetzt, daß er die erforderliche Einlage zu bemeldten Institut zu bestreiten außer Stand ist.

Owing to the unfortunate revolutions and the lengthy war, the livelihood of the undersigned, which made good progress based on the shipment of small ivory works to foreign countries, has been cut back to such an extent that he is unable to raise the necessary deposit for the membership in the aforesaid institution.

Paul Heß's letter to Empress Marie Therese (A-Wsa, Private Institutionen, Pensionsgesellschaft bildender Künstler, A1/1)

Of course, the Empress granted Paul Heß a free membership in the

Pensionsgesellschaft bildender Künstler. His financial situation, however, did not improve. At least he was able to procure a secure job for his son Franz Joseph (b. 8 April 1774 [A-Ws, Tom. 138, fol. 109r]), who, being employed as

Ingrossist der K.K. Tabakgefällsbuchhalterei, provided housing and financial support for his parents. On 17 May 1798, Paul Heß committed suicide by drowning himself in the Danube. His body was found almost one month later, and on 13 June 1798, was autopsied in Vienna's General Hospital (

Alservorstadtkrankenhaus 7, fol. 52). The entry in the municipal death register reads as follows.

Heß, Paul Graveur von N° 14 in der Josephstadt, welcher in der Donau ertrunken gefunden, und im Allgemeinen Krankenhaus gerichtl[ich] besch[au]t worden, alt 54 J[ah]r. Seifert [coroner]

Paul Heß was survived by his wife, his son Franz Joseph, and his daughter Katharina (b. 25 October 1778 [A-Ws, Tom. 39, fol. 121v]). He left absolutely nothing and therefore his estate was "armuthshalber abgetan" (discounted owing to poverty) by the civil court. The Emperor, who was notoriously interested in cases of murder and suicide, took keen interest in Heß's tragic death, and the protocol of the Imperial Cabinet-Chancellery (

A-Whh, Protokoll der Kabinettskanzlei 139, Nr. 955) duly notes: "Hess, Paul Elfenbeingraveur. Hat sich wahrscheinlich wegen Schulden in der Donau ersäuft." ("Hess, Paul ivory engraver. Drowned himself in the Danube presumably because of debts."). Not surprisingly, in the course of the legal proceedings at the civil court, none of Paul Heß's three brothers reported to the authorities. It seems that the rift between Paul and Sebastian was mainly caused by Paul's inability to pay back money his brother had lent him. In 1799, Paul's son Franz Joseph Heß was promoted to the rank of

Raitoffizier (accounting official), he married (Altsimmering, Tom. 5, fol. 56), and together with his wife and his sister moved to his new place of employment in West Galicia.

Paul Heß was not easily forgotten. In 1799, his friend, the Austrian poet

Johann Carl Unger published a collection of dedication poems titled

Feierstunden. Wiens Bewohnern gewidmet (bey I. Alberti's Wittwe) that contains an "Elegie auf den Tod des biedern Künstlers Paul Heß" ("Elegy to the death of the honest artist Paul Heß").

In Unger's poem (of which the remaining five stanzas can be read on Google books) we also learn that Paul Heß was a proficient singer.

I do not know where Constanze Mozart's pearl necklace is today. Regardless of its current location – whether it is lost or held by the Mozarteum – its value increases immensely by the identification of the creator of its clasp. Only about 100 ivory micro-carvings are known today worldwide. Most of the Heß brothers' masterpieces are held by the

Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the British Museum, and the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg. The inexplicable mastership of the art of Sebastian and Paul Heß will never cease to amaze.

© Dr. Michael Lorenz 2012. All rights reserved.

Updated: 7 August 2024