Den 16tenMozart Wohledler H:[err] Wolfgang, K:K: Kapelmeister / s.[ein] frauengetauftes K[ind] Kristian, so bei St. Nicolai /N° 245 am Judenplatz an der Fraißen von / Mutterleib besch[au]t word[en] M[atthäus] R[auscher]

Sir Wolfgang Mozart, imperial and royal Kapellmeister, his child Kristian, baptized in emergency, at St. Nicholas No. 245 on the Judenplatz was inspected [as having died] of spasms right after its birth. Matthäus Rauscher [coroner]

This short-lived Christian Stadler was a younger brother of the legendary clarinet players Anton and Johann Nepomuk Stadler. Here is an example from the death records of the Vienna Schotten parish:[Den 10 Oktober 1763]Stadler Joseph ein Schuhmacher sein Frau[en] ge- / tauftes Kind Christian, ist auf der / Windmüll beÿn Grün Thor an d.[er] / Frais b[e]sch[au]t word[en] nachmittag um / 4 uhr Gebohr[en] word[en] J:[ohann] C:[hristian] B:[aldamuß] (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 57, S, fol. 74v).

Den 30 dito [November 1709] deß Herr[n] Johann / Baptist Hilverting Comedianten / Brincipal, sein Nothgetauftes Kind Christian, in dem Ballhauß, in der / [T]ainfaltstr[aßen] 15 [Kreuzer] (A-Ws, Tom. 2, fol. 119r)

The father of this child Christian was the legendary puppeteer and actor Johann Baptist Hilverding, the father of the dancer Franz Anton Hilverding. Here is an example from the 1734 Totenbeschauprotokoll:

When on 17 November 1789, the burial of Mozart's daughter was reported and paid for at the Bahrleiheramt of St. Stephen's (the office that collected burial fees for the Vienna Magistrate), the child's name was still unknown. This resulted in the following entry in the 1789 Bahrleihbuch (which was first published in June 2009, in my article "Mozart's Apartment on the Alsergrund").

This is one of six documents I published in 2009 that show Mozart as being addressed with the appropriate particle of nobility "von". By now, the Bahrleiher already knew that the child was a girl, but the continuing uncertainty regarding the child's real name is reflected in the index of the particular volume of the payment records where the "fraugetauftes Mädchen" is given as "v:[on] Mozart Kristina".

We would not know the first name of Mozart's second daughter, if not one of its parents had told Johann Herbst, the priest of the parish church Am Hof, that the child's name was Anna.

The first scholar who delved into the Viennese church records related to Mozart's children was Emil Karl Blümml (1881–1925) who in 1919, published an article entitled "Mozarts Kinder", in Mozarteums Mitteilungen, Mai 1919, Heft 3, p. 4 (which he published again in his 1923 book Aus Mozarts Freundes und Familienkreis). Commendable as Blümml's work was 94 years ago, his article does not meet present-day standards, because he overlooked several important sources and misunderstood some of the documents. Blümml's flawed work became a problem only decades later, when in his 1961 edition of Mozart documents, Otto Erich Deutsch decided to spare himself the effort of checking the Viennese parish records in favor of simply referring to Blümml's completely out-of-date article. Deutsch's intriguing aversion to ever step inside a Viennese parish office is one of many reasons why some Viennese Mozart sources remain unpublished to this very day. As far as the name "Kristian" Mozart in the death records was concerned, Blümml had no idea what it meant and showed himself slightly baffled.

© Dr. Michael Lorenz 2013. All rights reserved.

Updated: 26 April 2025

Francesco Alborea (b. 1691 in Naples, d. 20 July 1739 in Padua [not in Vienna, as given in every encyclopedia]) was one of the most important cello virtuosi of the eighteenth century. He is frequently confused with his son Francesco, the cellist known as "Franciscello". Here is another, final example from the 1776 records of St. Michael's, concerning a female child named "Christina".[9 November 1734]Dem Herrn Francisco Alborea, Kaÿ[serlichem] Hof=Musico / sein Kind Christian, ist in Stadtschloßer[ischen] Hauß am Hof frauen Getaufter an der Frais b[e]sch[au]t worden. (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 37, fol. 244r)

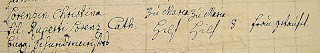

[9 January 1776]Lorenzin Christina / fil:[ia] Ruperti Lorenz / bürg: Schneidermeisters / Cath:[olisch] Zu Maria / Hilf [No.] 8 frau getaufet. (A-Wstm, Tom. 9, p. 187)

Mozart Rub:[rica] 4ta / 2te Class / Pfarr / am / Hofe. / Dem Tit[ulo] Herrn Wolfgang v:[on] / Mozart K:K: Kapellmeister sein / frauget.[auftes] Mädchen, am Juden= / =platz bei St. NickolaiNro 245. / an d[er] Frais von Mutterleib be = / = schaut, alt – / Im Freÿdhof A:[ußer] Mazlstorf / Bezahlt p [Partheÿen] 1.20. – [Kirche] 30 - / [Summa] 1 f 50 x

Mozart, 4th category, 2nd class, parish Am Hof, a girl baptized in emergency of Herr Wolfgang von Mozart, imperial and royal Kapellmeister, on the Judenplatz at St. Nicholas No. 245, was inspected [as having died] of spasms after her birth. In the cemetery beyond Matzleinsdorf, paid 1 f 20 x [the personnel] 30 x [the church] [overall sum] 1 Gulden 50 Kreuzer. (A-Wd, Bahrleihbuch 1789, fol. 377r)

We would not know the first name of Mozart's second daughter, if not one of its parents had told Johann Herbst, the priest of the parish church Am Hof, that the child's name was Anna.

The entry concerning the obsequies of Mozart's daughter Anna on 17 November 1789, at the parish church "Zu den Neun Chören der Engel" Am Hof: "Dem Herrn Wolfgang von Mozart K. / K. Käpelmeister sein Kind Anna [Lebensjahre] 1 Stund" (Am Hof, Tom. 1, fol. 48). The picture shows the two halves of the entry whose original goes across two pages.

The first scholar who delved into the Viennese church records related to Mozart's children was Emil Karl Blümml (1881–1925) who in 1919, published an article entitled "Mozarts Kinder", in Mozarteums Mitteilungen, Mai 1919, Heft 3, p. 4 (which he published again in his 1923 book Aus Mozarts Freundes und Familienkreis). Commendable as Blümml's work was 94 years ago, his article does not meet present-day standards, because he overlooked several important sources and misunderstood some of the documents. Blümml's flawed work became a problem only decades later, when in his 1961 edition of Mozart documents, Otto Erich Deutsch decided to spare himself the effort of checking the Viennese parish records in favor of simply referring to Blümml's completely out-of-date article. Deutsch's intriguing aversion to ever step inside a Viennese parish office is one of many reasons why some Viennese Mozart sources remain unpublished to this very day. As far as the name "Kristian" Mozart in the death records was concerned, Blümml had no idea what it meant and showed himself slightly baffled.

Während das kirchliche Protokoll von einem Kinde weiblichen Geschlechtes spricht, verzeichnet das amtliche Beschauprotokoll der Stadt Wien unterm 16. November 1789 einen Knaben. Wer hat demnach recht? Es sei nur bemerkt, daß der Name Christian bei Katholiken zu den Seltenheiten gehört.

While the entry in the parish register speaks of a girl, the official register of deaths of the City of Vienna for 16 November 1789 lists a boy. Which, then, of the two entries is correct? It should be mentioned that the name "Christian" is rare among Catholics.

© Dr. Michael Lorenz 2013. All rights reserved.

Updated: 26 April 2025