Stauffer's alternative violin design from 1828. That the upper part seems wider than the lower one, is an optical illusion.

On 25 July 1828, Stauffer and his son Johann Anton received a patent for this design which they let expire in 1833: "The upper part has the same length and width as the lower one and the bridge is located at the exact center of the body. The sound opening does not have the usual shape of an f, but that of a narrow half moon. The outer elliptical form also provides the instruments with a shape that distinguishes them from the regular ones."

A description of Stauffer's patented new design for violins, violas and cellos. (Beschreibung der Erfindungen und Verbesserungen etc., Vienna, 1841, p. 278)

Stauffer was simply unwilling to accept that the traditional design of stringed instruments represented an irreformable ideal that could not be improved. The amount of time and material he invested into his experiments must have been enormous. On 5 September 1832, Stauffer and his son submitted the following patent for the improvement of violins:

Invention concerning the building of violins, violas and violoncellos, whereby 1) these instruments, without distinguishing themselves from ordinary ones, by means of a purposeful inner device gain so much in tone that no instrument, not even the best old Cremona violin can even remotely match them in strength and beauty of tone; 2) the outer shape of these instruments is completely different from the conical ones that were patented on 25 July 1828, and finally 3) the bridge is located at the center of the body, while the body below the bridge is a little longer than those of conventional instruments, without causing the slightest impediment for the player. (A-Wsa, Hauptregistratur, Department H, 45908/1832)

A typical Stauffer guitar with a clock-key adjustment for the neck and a Stauffer headstock which is is basically the forerunner of a Fender Stratocaster headstock.

Stauffer also invented the Arpeggione, a musical instrument that is tuned like a guitar and played with a bow like a cello. This typically creative Stauffer invention would be long forgotten, had Franz Schubert not written his Arpeggione sonata D 821 for this instrument.

I have been collecting sources and documents concerning Johann Georg Stauffer's life for many years, and the recent opening of the exhibition "Early American Guitars" at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, which is presenting the guitar builder Christian Frederick Martin as having been Stauffer's apprentice, provides me with the opportunity to deal with this particular topic again, and to summarize my findings. I do not intend to present a detailed biography of Stauffer. This post serves the purpose of presenting a number of rare and little known archival documents. Some of them have already been published in Erik Pierre Hofmann's beautiful book Stauffer & Co, but since Hofmann seems to have invested most of his efforts into nice photographs instead of archival research, his book does not cover all the significant sources that are accessible in Vienna's archives.

Mathias Staufer and his Three Wives

Georg Stauffer's father Mathias was born on 4 June 1726, in the Upper Austrian village of Weyregg am Attersee, son of the binder Mathias Staufer and his wife Elisabeth, née Tremel.

The entry concerning the wedding of Johann Georg Stauffer's grandparents Mathias Staufer and Elisabeth Tremel from Blümelsau on 12 May 1716, in Weyregg. Johann Georg Stauffer's great-grandfather Zacharias Stauffer hailed from the village of Reichholz near Weyregg. (Weyregg, St. Valentin, Tom. 3, 12 May 1716)

The baptismal entry of Johann Georg Stauffer's father Mathias (Weyregg, St. Valentin, Tom. 4, 4 June 1726)

Mathias Staufer's first appears in Viennese sources on the occasion of his first marriage on 6 February 1759, to Theresia Schreiber, a hunter's widow. The entry in the marriage records of St. Stephen's shows that the surname's later spelling "Stauffer" is based on the well-known misreading of an old double-stroke single f. Mathias Staufer at that time was employed as a Haußmaister (janitor).

The entry concerning the first marriage of Johann Georg Stauffer's father on 6 February 1759. The witnesses Stephan Ächlehner and Urban Polt were both masons and janitors. The bride's former husband Lorenz Schreiber had died at the hospital of the Brothers Hospitallers of St. John of God (A-Wd, Tom. 59, fol. 125r).

Theresia Staufer died of fever on 29 August 1775 (the date in the Wiener Zeitung is wrong), at the age of 63, in the "Dreifaltigkeitsspital" on the Alsergrund. Mathias Staufer's second wedding took place on 6 February 1776. His second wife was Elisabeth Fichtauer (Viechthauer), who had been born on 15 November 1737, in Krummnußbaum (Pöchlarn 1, p. 21). She had come to Vienna in 1765, and for two years had been working as cook for Johann Pranberger, a maker of "Hungarian strings" (textile trims that were used for Hungarian garbs) in the house Stadt 681. In 1776, Mathias Staufer's profession was given as "Trager" (bearer) and he was living in the house "unter den Weißgerbern N 44".

The entry concerning the second wedding of Johann Georg Stauffer's father and his second wife Elisabeth Fichtauer on 6 February 1776 (A-Wd, Tom. 70, fol. 50r)

Mathias Staufer's seal and signature on his 1776 marriage contract (A-Ws, AZJ, A1, 13091/18. Jhdt.)

Mathias Staufer's second wife Elisabeth already died of childbed fever on 30 September 1776, after the birth of a stillborn son.

The entry in the Vienna municipal death records concerning Elisabeth Staufer's death: "Staufer Mathias ein Trager sein Weib Elisabeth ist samt ihren fraugedauften Knäblein in Flecksieder Hauß N° 44. unter weißgärber[n] nach d. Endbindung an Brand v[er]sch[ieden] alt 37 J[ahr] früh nach 10 Uhr vschid F[ranz Anton] S[chmid]" (A-Wsa, TBP 70/2, S, fol. 85v).

Elisabeth Staufer died penniless, and, because her widower had to borrow the money for the funeral, the value of her estate was disregarded by the municipal civil court.

A clip from Elisabeth Staufer's Sperrs-Relation drawn up by the Sperrs-Kommissär Johann Florian Lovin (A-Wsa, AZJ, A1, 222/20)

Mathias Staufer's third wedding took place at St. Stephen's on 12 January 1777. His third wife was Eva Rosina Magitzer from Mariazell, who was employed as servant in the house "Zum Blauen Igel" ("The Blue Hedgehog") at Tuchlauben 571 (today Tuchlauben 14).

Mathias Staufer's third marriage on 12 January 1777, in the records of St. Stephen's Cathedral (A-Wd, Tom. 71, fol. 57v and 58r). Owing to the loss of the Mariazell birth register from 1716-38 in the 1827 fire, the bride's date of birth cannot be determined.

Mathias Staufer died between 1778 and 1802. Since his name does not appear in the Viennese death records, it is possible that he returned to Upper Austria and did not die in Vienna.

Johann Georg Stauffer

Johann Georg Stauffer was born on 26 January 1778, in the house Weißgerber No. 44, "The Holy Trinity" which at that time belonged to the "bürgerlicher Flecksieder" (civil tripe cooker) Leopold Gänsbauer.

Because it was located along the Danube, downstream from the inner city, the suburb of Weißgerber was the main residence of Vienna's tanners, butchers, tripe cookers and "Darmwäscher" (intestine washers).

Johann Georg Stauffer's place of birth, the house Weißgerber No. 44 (today Obere Weißgerberstraße 28) on Joseph Daniel von Huber's 1778 map of Vienna (W-Waw, Sammlung Woldan).

The house Weißgerber No. 44 in the municipal tax register from 1788 (A-Wsa, Steueramt B34/10, fol. 50). Mathias Staufer is not recorded in this document.

Johann Georg Stauffer's baptismal entry in the 1778 records of St. Stephen's Cathedral. Stauffer's godparents were the "Tagwerker" (laborer) Johann Georg Sig and his wife Theresia. (A-Wd, Tom. 94, fol. 128r)

After starting out as a carpenter and finishing his apprenticeship with Franz Geissenhof, Stauffer, in 1800, took over the shop of violin maker Ignatz Partl (1732–1819), and on 20 June 1800, took the oath as Viennese citizen.

Johann Georg Staufer taking the oath as "Wiener Bürger". The signature below Staufer's is that of the guild's head Mathias Thir (A-Wsa, Sonderregistraturen, Bürgereidbuch B1/10, fol. 70r)

The signatures of the violin makers Ignatz Partl and his brother Christian. Stauffer took over Ignatz Partl's shop in 1800 (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 1792/1801).

Staufer (second from the top) in a list of Viennese luthiers in an 1800 tax register. As can be seen, Mathias Thir and Michael Stadlmann enjoyed the highest profits. (A-Wsa, Steueramt, Unbehaustes Catastrum B10/35, fol. 66r)

Stauffer's Marriage

On 16 May 1802, Johann Georg Stauffer married Josepha Fischer, a chambermaid from Leitmeritz. The entry concerning the wedding in the records of the Schotten parish was published by Erik Pierre Hofmann. What has not been published until now is the following document concerning the only publication of the banns (the couple was dispensed from the other two) on 11 May 1802, at St. Michael's, the home parish of the groom. Unlike the actual marriage entry from five days later, this document contains the groom's address.

The previously unpublished entry concerning the publication of the banns for Stauffer and his bride on 11 May 1802 (A-Wstm, Verkündbuch 27, 1360)

No 43 11 Maÿ Cath[olisch] 24 J[ahre] H[err] Ignaz <Georg> Staufer bürgl: Geigenmacher von hier geb[ürtig] L[edigen] St[andes] des Mathies Staufer eines Taglöhners seel[ig] und der noch lebenden Eva geb[orene] Magetzer, beid[er] ehel[icher] SohnN° 311 im Neubaad. Mit der Josepha Fischer herrsch[aftliche] Kammerjungfer von Leitmeritz in Böhmen. Cath: 24 J. geb: des H: Johann Fischer bürg[erlichen] Parockenmachers annoch am Leben, und der Waldburga geb: Potozka seel: beid: ehel: TochterN° 82 in Klepperstall.

1in 2da et 3tia dispensati

[Testes] Franz Edler v Ržehatscheck. K.K: Hof Concipist. H: Johann Wiedmann bürg[erlicher] Perokenmacher.

bezahlt. Verkündschein erhielt den 16ten Maÿ.

The house Neubad 311 (last number 289), where Stauffer lived in 1802, was located between Naglergasse and Wallnerstraße, beside the Palais Esterházy and at that time belonged to the heirs of Carl von Pauerspach.

When in 2011 Erik Pierre Hofmann published a picture of Stauffer's marriage entry in the Schotten records, he misread the name of Stauffer's best man Franz Rzehaczek as "Ignaz Schuppanzigh". This is all the more surprising considering the fact that in April 2010, I had personally told Hofmann that Stauffer's groomsman was the instrument collector Franz Rzehaczek.

The house Stadt 311 (bearing the old number 181) on Huber's 1778 map of Vienna. The street on the left is the Kohlmarkt, the square on the right is a corner of Am Hof (W-Waw, Sammlung Woldan).

When in 2011 Erik Pierre Hofmann published a picture of Stauffer's marriage entry in the Schotten records, he misread the name of Stauffer's best man Franz Rzehaczek as "Ignaz Schuppanzigh". This is all the more surprising considering the fact that in April 2010, I had personally told Hofmann that Stauffer's groomsman was the instrument collector Franz Rzehaczek.

The entry concerning Georg Staufer's[!] wedding on 16 May 1802, in the records of the Schottenkirche. Note the missing house number in the groom's address. The bride was dispensed from submitting her birth certificate. (Pfarre Schotten, Tom. 49, fol. 17)

The names of the two witnesses in Stauffer's marriage entry. Hofmann seems to have had an apparition of Schuppanzigh's name in the word "Hofkonzipist". He also mistranscribed the surname of the groom's mother as "Magahrer".

Franz Rzehaczek

Who was Stauffer's best man? Franz Georg Rzehaczek was born on 6 August 1758, in the Bohemian village of Lichtowitz (today Litochovice nad Labem), son of Joseph Rzehaczek, a "k.k. Wirtschafts-Direktor" (I. & R. business manager) and his wife Anna Dorothea, née Czernay.

The entry concerning the baptism of Franz Rzehaczek in the 1758 register of St. Matthew's church in Prackovice nad Labem (Státní oblastní archiv v Litoměřicích, 135/1, fol. 274v)

In the late 1770s, Rzehaczek came to Vienna to study law. On the occasion of his first marriage in November 1786, to Amelie de Ritter (born 1759 in Ypres), he is described as "Practicus juris" (A-Wd, Tom. 76, fol. 98v); in the following year he is referred to as "Führungs-Commissair" (executive commissary), and in 1792, he was promoted to "Concipist bey der königlich böhmischen Hofkanzley". With his first wife he had four children: Elisabeth (b. 27 May 1787, d. before 1792), Philipp (b. 1 September 1788, d. 1789), Maria Anna (b. 6 January 1790, d. 1790), and a nameless daughter who was baptized by the midwife and died soon after her birth on 15 May 1792. The mother Amelie Rzehaczek died the following day of "Magenentzündung" (inflammation of the stomach) (Wiener Zeitung, 23 May 1792, p. 1435).

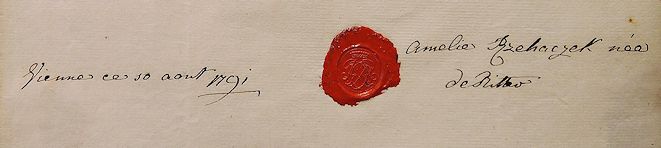

Amelie Rzehaczek's seal and signature on her 1791 will (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 1402/1792)

Rzehaczek's second wife Theresia Krückel, whom he had married on 13 October 1794 (A-Wd, Tom. 78, fol. 247), already died of tuberculosis on 1 December 1795, at the age of nineteen.

The entry concerning the burial of Franz Rzehaczek's second wife Theresia on 3 December 1795. This was a regular 3rd class burial (comparable to Mozart's) for eight gulden and fifty-six kreuzer, plus three gulden for the carriage to the St. Marx Cemetery. Note the widower's wrong first name "Seraph" (A-Wd, Bahrleihbuch 1795, fol. 272v).

On 12 October 1806, Rzehaczek's integration into a network of musicians and violin makers culminated in his marriage to Ignaz Schuppanzigh's elder sister Theresia (b. 22 August 1773).

The entry concerning Franz Rzehaczek's wedding to Theresia Schuppanzigh at St. Stephen's. The groom's witness was the personal physician of the Polish king Dr. Joseph Tiussi von Bourgnanemburg, the witness of the bride was her brother-in-law, the "k.k. Hof=Ballmeister" (tennis coach) Ignaz Martin (A-Wd, Tom. 81, fol. 193).

With his third wife, Rzehaczek had the following five children (with the name of their godparents in parentheses).

- Barbara Theresia, b. 29 August 1807 (Barbara Schuppanzigh, Ignaz Schuppanzigh's wife), d. before 1840.

- Anna Maria ("Nina"), b. 21 December 1808 (Anna Schuppanzigh, Ignaz Schuppanzigh's mother), was a pupil of Carl Maria von Bocklet and became a noted pianist, d. 20 January 1876 in Vienna.

- Franz Seraph, b. 21 August 1811 (Joseph Linke, "Kammervirtuos bei Sr: Excell: Herrn Graf v. Rasumofsky"), became a military officer, d. after 1840.

- Karl Ägidius, b. 2 September 1816 (Karl Gradl), studied medicine, became a renowned surgeon in Salzburg and Graz, a sculptor and painter and was ennobled with the predicate "Ritter von Rzehaczek"; on 9 August 1854, he married Countess Karoline Leopoldine von Auersperg (1820–1899), d. 25 December 1897 in Graz.

- Maria Johanna, b. 27 September 1814 (Johanna Crüwell, "Stallmeisterswitwe bei Prinz Carl"), d. before 1840.

Rzehaczek was the best man of Ignaz Schuppanzigh, Joseph Linke,

the luthiers Johann Georg Stauffer, Peter Teufelsdorfer, Christian Friedrich Martin, Franz Schmidt, Ludwig Deák (an apprentice of Stauffer), the piano builder Franz Karl Schneider,

and Beethoven's copyist Wenzel Schlemmer. He also served as godfather of many children of other musicians and violin makers.

Franz Rzehaczek's signature in the entry concerning the baptism of Wenzel Schlemmer's son Franz Anton on 12 May 1812, at St. Michael's (A-Wstm, Tom. 19, fol. 118).

Rzehaczek owned the most important private collection of stringed instruments in Europe (consisting of more than a hundred pieces), among them all kinds of Stradivari, Amati and Guarneri masterpieces. In 1823, Anton Ziegler wrote "This collection of instruments has been famously renowned for years and – because it is absolutely unique and a similar one has never been seen – it is all the more admired by connaisseurs, experts of the craft and virtuosi, because it contains several items that are extremely rare and

of which similar pieces do not exist."

The description of Rzehaczek's collection in Anton Ziegler's 1823 Addressen-Buch von Tonkünstlern, Dilettanten, Hof-Kammer-Theater- und Kirchenmusikern ... in Wien.

Franz Rhehaczek's expertise in matters of violin making being noted in vol. 3 of the 1835 edition of Johann Jakob Czikann's National-Encyclopädie: "Rzehaczek has valuable expertise regarding the building and improvement of bowed instruments which unfortunately he will take with him to his grave, because violin makers are too negligent, to let themselves be taught."

Rzehaczek's collection being referred to on p. 3 of Arnold's Magazine of the Fine Arts and Journal of Literature and Science, vol. III, (London 1834). Mr. "Alexander" Fuchs is of course the collector Aloys Fuchs (Fuchs's date of birth on Wikipedia is wrong, he was born on 23 June 1799).

The most famous item in Rzehaczek's collection was a violin by Gasparo da Salò whose origin has always been shrouded in mystery.

Ole Bull's Salò violin. The claim that its pegbox was carved by Benvenuto Cellini is an urban legend.

The instrument had allegedly been stolen in 1809, in Tyrol, by a French soldier and been brought to Vienna where Rzehaczek bought it. When in 1839, the great Norwegian violinist Ole Bull gave several concerts in Vienna, he also visited Rzehaczek's collection and immediately fell in love with the Gasparo da Salò violin. Rzehaczek told Bull that if he would ever sell it, Bull would be given a preemptive right at a price of 4,000 ducats.

The signatures of Franz Rzehaczek and his wife Theresia, née Schuppanzigh on an undated contract of community of property which became Rzehaczek's will. Rzehaczek's brother-in-law Mathias Schuppanzigh and the lawyer Dr. Anton Mosing signed as witnesses (A-Ws, Mag. ZG, A10, 656/1840).

After Rzehaczek's death on 22 November 1840 – to the great astonishment of the officials of the Vienna municipal court –

the precious collection of instruments and scores had disappeared, and the value of Rzehaczek's belongings was estimated at only 203 fl 20 x. The Sperrs-Kommissär expressedly referred to the surprising dissappearance of this famous collection as follows:

The widow Theresia Rzehazek is summoned to attest her medical fees and burial expenses and both major children, Anna and Karl Rzehazek are to testify whether there are any other assets in the estate aside from the listed ones, namely if there is no valuable collection of musical instruments and musical scores [...]

The court official's entry in Rzehaczek's probate records concerning the vanished collection of instruments (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 7412/1840).

Of course, Rzehaczek's collection had only been hidden from the authorities, probably in the apartment of Rzehaczek's son. Immediately after her husband's death, Theresia Rzehaczek commissoned the violin maker Wilhelm Rupprecht (born around 1810 in Schlause in Silesia, today Służejów) to classify the instruments and prepare the collection for being put on sale. In the following year, Bull – as promised – was contacted by Dr. Karl Rzehaczek, and in 1842, bought the Salò violin for 4,000

ducats from Rzehaczek's heirs. The unique and priceless instrument is now on display at the Vestlandske kunstindustrimuseum in

Bergen.

Ole Bull in 1846 with the Salò violin he had bought from Rzehaczek's heirs (National Library of Norway)

Franz Rzehaczek, signing in 1817, as "k.k. Hofkonzipist and representative of his brother-in-law Ignaz Schuppanzig who is currently in Lemberg" (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 754/1817).

Stauffer's Three Sons Franz, Anton and Alois

Johann Georg Stauffer had three sons: the first one, Franz Seraph Georg Staufer, was born on 25 March 1803, and baptized in his father's apartment in the house Stadt 311 with Franz Rzehaczek serving as godfather.

The entry concerning Franz Seraph Georg Staufer's baptism on 25 March 1803, in the house Stadt 311 ("in Hause getauft") (A-Wstm, Tom. 18, fol. 224). Erik Pierre Hofmann erroneously gives March 28th as Franz Stauffer's date of birth.

Franz Staufer was a musical child prodigy and an excellent pianist. On 25 December 1815, he performed Hummel's Rondo Brillante op. 56 at a charity concert at the Vienna Redoutensaal. In 1819, he travelled to Lemberg, where he was employed by the Polish-Armenian nobleman Joseph Antoniewicz as piano teacher for Antoniewicz's son Karol (1807–1852).

Franz Staufer being referred to as piano teacher ("Klaviermeister") on 2 October 1819, on the occasion of the issuance of a passport "to Lemberg in Poland to take service with Joseph de Botoz[!] Antoniewicz as piano teacher". (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamtl B4/5, fol. 214). In April 1820 Josepha Stauffer visited her son Franz in Lemberg. (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt B4/6, fol. 57)

On 12 September 1826, Franz Staufer renewed his passport for a journey to St. Petersburg. An entry in a protocol of the Hauptregistratur of the Vienna magistrate proves that he was still alive in 1846.

Franz Staufer's name appearing in an 1846 Viennese administration protocol (A-Wsa, HReg. Politica B1/549, p. 592). Hofmann erroneously suggests that Franz Staufer already died in the 1820s.

In 1823, Franz Staufer received a passport to the city of Berdyczów (then in Russia, today Berdychiv in Ukraine) which he had extended in 1824 and 1825. It is not known if Franz Staufer ever returned to Vienna. Also unknown is his date of death.

Between 1803 and 1805, Johann Georg Stauffer moved his violin making workshop from the inner city to the house "Zum Ungarischen König" No. 152 (today Mariahilfer Straße 11) in the suburb of Laimgrube. There, on 12 June 1805, his second son Anton Staufer was born and baptized in the parish church St. Josef ob der Laimgrube. Stauffer's landlord, the distiller Anton Lichtmayer served as godfather.

Anton Staufer's baptismal entry in the records of St. Josef ob der Laimgrube (Tom. 9, fol. 26)

Anton Staufer also became a pianist and performed in public several times. In 1825, he went to Sniatyn (then located in Russia), where he seems to have worked as piano teacher. He eventually renounced his musical career and decided to follow the footsteps of his father as a violin maker. By 1826, he worked full-time in his father's shop and in 1827, he joined his father's company. In 1833, when his father resigned from his job as violin maker, Anton was granted the official "Befugnis" (permit of craftsmanship).

Anton Staufer applying for a "Befugnis" (permit) as violin maker in 1833, and, at the same time, his father Johann Georg Stauffer resigning from his profession ("sagt sein Gewerbe anheim"). Note the different spelling of the surnames. (A-Wsa, HReg., Politica B1/421, fol. 179r)

On 4 February 1841, Anton Staufer took the oath as Viennese citizen. On 22 February 1841, he married Maria Wranitzky, née Speil von Ostheim (b. 1797 in Brno), who was the widow of the cellist Friedrich Wranitzky (b. 13 May 1798), a son of Count Lobkowitz's capelmeister Anton Wranitzky.

The entry concerning the wedding of Anton Staufer and Maria Wranitzky, née Speil von Ostheim in 1841 (St. Augustin, Tom. XI, fol. 57).

In 1832, Friedrich Wranitzky (who by then had already separated from his wife) had gone to Berlin, where he was engaged at the Königstädter Theater

as a cellist. In 1839, he was in Dresden, where on 10 December 1839 –

being without permanent employment and threatened with deportation – he

jumped into the Elbe and died soon after. What is unknown among Stauffer

experts is the fact that Anton Staufer's wife was a sister-in-law of

the composer Konradin Kreutzer.

The signature of Marie Stauffer "geb. Edle von Osteim"

Marie von Ostheim together with her brother-in-law Konradin Kreutzer, her sister Anna, and her nieces Cäcilie and Maria on an 1830 conscription sheet of the house Stadt 1038 (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Stadt 1038/20r)

Just like his father's, Johann Anton Staufer's guitars were masterpieces that were sought-after by musicians and connaisseurs. Anton Staufer already resigned from his profession in 1848. On 28 October 1871, he died in the house Wiedner Haupstraße 19.

The house Wiedner Hauptstraße 19 where Anton Staufer died in 1871 (Wien Museum, I.N. 24377)

Because the immediate cause of death was unclear (in his book Hofmann mistakenly describes it as "mysterious"), Anton Staufer's body was inspected by the sanitary police which made the diagnosis "cardiac dilatation" (A-Wsa, Totenbeschreibamt 311/b, fol. 283). On 31 October 1871, Anton Staufer was buried in an "eigenes Grab" (own grave) in Matzleinsdorf. His widow Marie Staufer, née von Ostheim died of old age on 8 May 1875 at Kettenbrückengasse 9.

The previously unpublished original of Anton Stauffer's first will dated 2 November 1867 (A-Wsa, BG IV, A9, 128/1871). On 13 June 1868, Stauffer added a codicil, in which he tacitly conceded that his supposed huge financial assets were gone (or rather had been imaginary in the first place). The document published by Hofmann (with an invalid shelfmark) is only a copy preserved in Stauffer's probate records (A-Wsa, BG Wieden, IV 1981/1871). Hofmann's book is unfortunately marred by countless wrong shelfmarks of archival documents. For example, none of the files from the 1833 Hauptregistratur is given with a correct shelfmark. In one case Hofmann misread the irrelevant number "H-186" as "4186" which led to the useless fantasy shelfmark "69374/4186" (the correct number being 69374/1833).

Anton Stauffer's grave No. 1228 listed in the nineteenth-entury register of "eigene Gräber" in the Matzleinsdorf cemetery. (A-Wsa, Matzleinsdorfer Kommunalfriedhof B2, alt: II-D-2, fol. 80r)

The existence of Stauffer's third son Alois, who was born on 7 June 1806, has previously escaped the attention of researchers which was obviously caused by the fact that this child already died in infancy. Therefore it does not appear on the conscription sheets that list the Stauffer family.

The entry concerning Alois Staufer's baptism in St. Joseph ob der Laimgrube (Tom. 9, fol. 92). Note that in this entry the parish priest Serapion Gläser in the name "Staufer" still uses the old double-stroke f which is a single f.

The boy Alois Staufer already died on 23 June 1806, of "Fraisen" (fever spasms) (St. Josef ob der Laimgrube 4, fol. 178).

Stauffer's Firm "Johann Georg Staufer & Comp."

On 1 August 1827, Johann Anton[!] Stauffer published an ad (Wiener Zeitung, 1 Aug 1827, 155) pointing out that only the guitars that bear a label with a patent seal, a serial number and the signature "J A St et Comp." are genuine Stauffer products. On 6 December 1827, the Wiener Zeitung (Amtsblatt, 903) reported about "the extension of a shared privilege for Anton Stauffer and Johann Nepomuk Ertl which in 1822 had originally been granted to Johann Georg Stauffer and Ertl, of whom the first had already passed his share to his son". A note in Anton Redl's 1827 Adressen-Buch, on the other hand, referred to the newly invented Hohlflügel (a piano, patented in June 1824, with a circular keyboard and keys decreasing in width towards the outside) being manufactured by "J. G. Staufer und Comp.", a company exclusively managed by the public shareholder Franz von Lacasse who lived at Stadt 415 (today Schulhof 2).

Confused by those three sources, that seem to refer to two different enterprises, Erik Pierre Hofmann in his book claims that in 1827, Stauffer established two independent companies:

After a year of transition [i.e. 1827], Georg Stauffer sets up two different enterprises: »Johann Anton Stauffer & Comp.«, makers of guitars, and »Johann Georg Stauffer & Comp.«, dedicated exclusively to producing in quantity a new instrument which he has developed himself with his colleague Maximilian Haidinger – a piano with a circular keyboard called the Hohlflügel.

Hofmann is wrong. Johann Georg Stauffer only established one single company and he did this already in 1825.

Franz Seraph von Lacasse was born on 8 August 1777, in the Hungarian town of Györ. He seems to have been an avid amateur musician with a deep emotional relationship to musical instruments and their manufacturing which could explain the fact that, by autumn of 1825, he already had lent Stauffer an overall sum of 877 gulden 44 kreuzer CM to finance Stauffer's guitar production (or rather his high-flying projects and inventions). In September 1825, when it became obvious that Stauffer was unable to pay back his debt, he offered a deal to the nobleman: if he would invest even more money into a joint enterprise, he would not only get his money back, but even make a profit with the sale of Stauffer's instruments. On 15 September 1825, Lacasse, Stauffer, and Stauffer's wife signed the founding contract of the firm "Johann Georg Staufer and Company". This contract consists of thirteen paragraphs and reads as follows.

- Mr. Georg Stauffer and Mr. von Lacasse establish a company for the purpose of manufacturing and selling all kinds[!] of musical instruments.

- Mr. Franz von Lacasse will have two thousand gulden ready to invest, while Mr. Stauffer will be obliged to make all instruments exclusively for the company. The same goes for all repairs of instruments as well as the new pegboxes for violins, cellos, and basses.

- To provide Mr. Stauffer with the means to produce perfect musical instruments it is agreed that for every delivery Mr. von Lacasse will pay Mr. Stauffer the following mutually agreed prices: for an ordinary guitar 10 fl WW (Viennese Currency), for a guitar of medium quality 12 fl WW, for one of medium quality with wooden screws and elevated fretboard 20 fl WW, for one guitar of finest quality with said two features 25 fl WW and for one with silver tuning action 45 fl 50 x WW. As soon as they are delivered, Mr. von Lacasse will be granted full ownership of these instruments and he will have the right to keep the surplus from the sale prices as his profit.

- It is resolved that Mr. Stauffer will use a quarter of the money he receives for his instruments for the repayment of the 877 fl 44 x that he borrowed from Mr. von Lacasse a long time ago, until this debt will be paid back completely.

- The wife of Mr. Georg Stauffer will be liable for the fulfilment of the agreed conditions and also vouches – in case Mr. Stauffer would for whatever reasons be unable to fulfil this contract – that she, Mrs. Josepha Stauffer will continue to produce the instruments with her staff, will take care of all the occurring repairs and will deliver the instruments to the salesroom.

- Mr. Stauffer has to pay all expenses concerning the company, namely: the rent of the salesroom, six percent interests from the fund of two thousand gulden and the bookkeeper's or the salesman's monthly salary of fifty gulden.

- The contracting parties are not allowed to ship instruments to other places on commission, except at their own risk, so that any loss will occur at their own expense, in case the payment does not arrive or the instruments are returned in damaged condition. If both parties agree to ship goods to third locations, they will share the damage in the aforementioned cases.

- If the company purchases goods on commission, both parties are liable for the value.

- In case Mr. Stauffer should depart with death during the term of this contract, Mr. von Lacasse can chose freely, whether to continue the contract with the widow, or to sell the stock of merchandise to another firm. In the latter case he is obliged to give the profit to the widow according to the above regulations within three months after the dissolution of the contract.

- This contract begins with the opening of a salesroom and cannot be cancelled within one year. After one year, Mr. von Lacasse has the right either to resign, or to extend the contract for a time of one, two, or three years, whatever time he may see fit, to which Mr. Stauffer and his wife have no right to take exception.

- The calculations concerning the profit will be done every three months, and at every calculation Mr. Stauffer's share of the profit, which will be used to cover the expenses mentioned in the paragraphs four to six, will remain in the hands of Mr. von Lacasse.

- Because the calculation of the interests for Mr. von Lacasse requires every sale of an instrument to be exactly registered, an exact and reliable protocol will be kept regarding the date of delivery, the purchase price, the price of sale and the date of sale.

- It goes without saying that in favor of the start and the expansion of the business only fine and beautiful instruments will be delivered and accepted that were produced by Mr. Stauffer in his own factory.

The final page of the business contract between Franz von Lacasse, Stauffer, and Stauffer's wife. The undersigned witnesses were the lawyer Dr. Joseph Uibl and Johann Georg Hundriser. (A-Wsa, Merkantil- und Wechselgericht 2.3.2.A3.S 471)

Before Stauffer and Lacasse could start their business, they had to compensate Stauffer's colleague Johann Ertl who still had financial claims on a patent that in 1822 he had filed together with Stauffer. This patent included the elevation of the fingerboard and its separation from the soundboard, the improvement of the headstock mechanics (the "Schraubenmaschine"), and the use of embedded metal frets made of a special alloy. Therefore Ertl signed the following disclaimer:

DeclarationBecause I, the undersigned, have reached an agreement with Mr. Johann Georg Staufer that the excluding patent which was granted to both of us on 9 June 1822 concerning the improvement of guitars with elevated fingerboards, screw machines and metal frets made of a special alloy can be used by both of us to its full extent, without entertaining any business relation because of this, Therefore, for me and my heirs I declare it formally legal: that I bear not the slightest objection against the business contract which on 15 September 1825 was concluded between Mr. Johann Georg Staufer and Mr. Franz von Lacasse. In witness whereof my and the two witnesses' signatures.

Vienna, 20 February 1826.

Johann Ertl

civil luthier

In my presence Friedrich Martin as witness

In my presence Andras Jeremias

as witness

Johann Ertl's disclaimer concerning his and Stauffer's patent from 1822 (A-Wsa, Merkantil- und Wechselgericht 2.3.2.A3.S 471).

This document is the only known Viennese source that bears the signature of Christian Friedrich Martin and proves an actual connection between Martin, Ertl, Jeremias, and Stauffer.

The luthier Andreas Jeremias was born around 1796, in Kronstadt (today Brașov) in Transylvania. He probably was a pupil of Stauffer and received a permit in 1831, which was cancelled the following year. On 10 March 1838, he died of tuberculosis at Mariahilf 130 (Lindengasse 11). The salesroom of "Johann Georg Staufer & Comp." was located at the beginning of the Kohlmessergasse at Stadt No. 480. The address Stadt 415, given by Ferdinand Prochart, does not apply to Stauffer's workshop, but refers to the residence of his associate Franz von Lacasse.

Stadt No. 480 (oldest number 672) at the end of the Rotenturmstraße on Huber's plan. This house was torn down in 1887, and the area is now a park (W-Waw, Sammlung Woldan).

The first page of Stauffer's privilege for the patent of "a tuning device for stringed instruments that facilitates and easily keeps the tuning" which on 2 July 1825, was issued by Emperor Francis I.

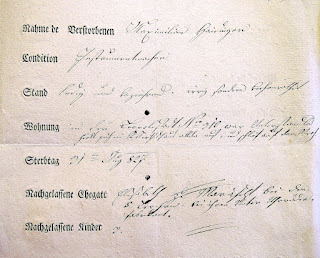

Stauffer's business plan turned out to be a failure, and eventually led to his resignation from the craft altogether. Contrary to the concept laid out in the company's founding contract, Stauffer never made enough profit to actually pay back his debt, and the reasons for this were twofold: 1) He was not prudent enough to rely on the popularity of his guitars and to just produce his top selling merchandise. 2) He continued to pursue his usual moot experiments and wasted his profits with the development and production of Maximilian Haidinger's ill-fated Hohlflügel which "especially facilitated playing for children", and whose lack of commercial success today appears quite predictable. In 1827, Stauffer transferred his share of the company, the 1822 patent, and the guitar production, to his son Johann Anton (Wiener Zeitung, 6 Dec 1827, 903). None of Stauffer's associates and colleagues fared well in the whole enterprise. The fate of two of them offers a grim look at the dark other side of Viennese piano building. On 31 August 1827, the inventor of the Hohlflügel Maximilian Haidinger died of "Brustwassersucht" (thoracic edema) in the hospital of the Brothers Hospitallers of St. John of God. Haidinger (b. 3 Jun 1784 in Vienna [Alservorstadtpfarre 2, fol. 3]), whose many applications to get a "Befugnis" (manufacturing permit) were never successful, had needed Stauffer's license to produce his Hohlflügel. His Sperrs-Relation (probate record) offers a harrowing look on the situation of an impoverished father of three who had already lost his home and left his family. At first, the court officials did not realize that the deceased was married and described him as "unmarried and travelling [vazierend]". Then it was discovered that Haidinger was married, had three children, and was "homeless and sleeping on straw at the inn at Leopoldstadt 310". His son Joseph, a tailor's apprentice, was living at the home of his employer in the city, and the daughter Theresia was staying with her mother, who had moved to her father, the clock wheel manufacturer Heinrich Stoppelhart at Neubau 192. Haidinger's youngest child Franz, aged nine, was living with his father at the inn. Haidinger left nothing but his clothes. His estate was "armutshalber abgethan" (discounted owing to poverty).

The description of a homeless and destitute piano builder and his family in Maximilian Haidinger's Sperrs-Relation (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 3088/1827)

The entry concerning the baptism of Johann Nepomuk Ertl on 6 May 1776, in the Moravian village of Kaidling (today Havraníky). The information given by Rudolf Hopfner in his book Wiener Musikinstrumentenmacher 1766-1900. Adressenverzeichnis und Bibliographie (Tutzing: Schneider 1999) that Ertl's first names were "Johann Anton" and that he was born in "Raidling" is false (Moravský zemský archiv Brno, 13609 Havraníky 1, p. 1).

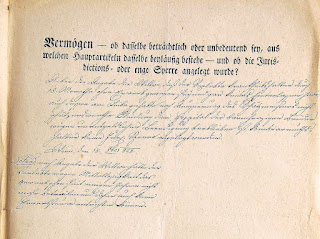

On 2 October 1828, Johann Ertl died destitute at the aforementioned hospital of "Schleichfieber" (creeping fever). His probate records show that, owing to illness and poverty, he had been unable to work during the last years of his life. The court official noted: "According to the widow, the deceased had been without income for eighteen months and left absolutely nothing except for the clothes he had on his body. According to the appraiser, these worthless clothes remained at the hospital, because of the free burial. Therefore no sequestering of the estate could be performed. To be noted: according to the widow, owing to poverty, the deceased had not been pursuing his profession for several years and therefore could not pay any income tax." Ertl's Sperrs-Relation ends with a note, dated 9 March 1829, stating that "the owed income tax amounting to 49 fl 50 x for the years 1823 and 1824, and 11 fl 3 x for 1827 could not be paid from the estate of the deceased, because owing to poverty it was discounted by the court."

The note on Johann Ertl's Sperrs-Relation concerning his illness and poverty that had kept him from working in the last years of his life (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 4343/1828)

The next among Stauffer's associates to pass away was his business partner and financier Franz von Lacasse. In the long run, Lacasse's death must be considered a piece of luck for Stauffer, because it finally put an end to the waste of Lacasse's money and reduced Anton Staufer's debt by fifty percent. Lacasse died of a stroke on 31 January 1829, at his home in Leopoldstadt 31. The copies of his probate papers and his will that survive in the holdings of Vienna's commercial court – the originals were destroyed in 1927 – show the financial situation of the firm "Stauffer & Comp." three and a half years after its establishment. Because Stauffer and his son never were able to pay back the old debt, its amount had not been reduced at all. The following assets were listed in the inventory of Lacasse's estate.

Four gulden Conventionsmünze in cash, two rings and two pocket watches, some linen, clothes and furniture. A debt claim of 7,000 gulden WW [Viennese currency, i.e. 2,800 gulden CM] against the maker of musical instruments Anton Stauffer, a promissory note for 600 gulden CM from N Hochser [the piano builder Friedrich Hoxa] and finally, the stock of merchandise at Johann Stauffer's shop. To be noted: the above jewels and the promissory note of 600 fl CM were taken into close sequestering as well as the clothing and linen.

Regarding my fortune which I was able to acquire through myself and the grace of God, I feel compelled to decree 1) that immediately after my death an inventory must be drawn up by the executor of my will in the salesroom that I established together with Johann August[!] Staufer at the end of Rothenthurmstrasse N° 480 and that this executor must manage the business until the whole stock of merchandise and all sorts of strings are sold (because all this is my own property which must be distributed between my sole heir and Mr. Anton Stauffer according the existing contract); 2) because Mr. Johann Anton Stauffer, according to the general balance that was completed on 15 October 1827, owes me a sum of 7,434 fl 24 xr WW, partly for the debt of his father and mother, partly for the money I lent him personally and the advance for managing the business, it is my wish that Mr. Stauffer will pay my sole heir a life annuity of 250 gulden per year. While I declare Mr. Anton Stauffer the heir of the aforementioned fund, this debt will cease as soon as my sole heir passes away. In case Mr Stauffer does not agree to the payment of the life annuity, he must pay half of the said amount in appropriate rates within three years, namely 1,200 fl every year, or 100 fl every month. The second half, i.e. 3,634 fl 24 xr, I bequeath to Mr. Stauffer. If however 3) Mr. Joh. Ant. Stauffer should be inclined to continue the business under the supervison of the executor according to the contract until the end of the business privilege, the executor should receive 500 gulden from my sole heir to cover all the expenses and keep an exact account. And after the completion of a total balance, except for his fee of 500 fl, every half year the executor should pay the share of the profit to my sole heir. After the dissolution of the company the executor of my will has to observe the rights of my sole heir according to paragraph No. 1.

Lacasse's closest relatives only received minor shares of the heritage. His brother Peter von Lacasse in Raab inherited a golden pocket watch on a chain and five hundred gulden in Viennese currency, the two children of Lacasse's sister Barbara Fähnrich in Preßburg each received the same amount of money. The universal heir of Lacasse's estate – and therefore the new owner of Stauffer's shop and its stock of merchandise – was Lacasse's old friend, the "Handelsmanns Wittwe" Klara Manueli.

Klara Manueli was born Klara Steininger on 3 August 1769, in the Upper Austrian village of Liebenau, daughter of the schoolmaster Joseph Steininger and his wife Theresia.

The entry concerning the baptism of Clara Steininger in 1769 (Liebenau, St. Joseph, Tom. 1, p. 42)

On 1 January 1797, in Gumpendorf, Klara Steininger married the Greek merchant Johann Manueli (Gumpendorf 13, p. 133f.) who had been born around 1771, in the Macedonian town of Meleniko (today Melnik in Bulgaria). Manueli was a business associate of the Greek industrialist and banker Kyro Nicolitz who owned the house Stadt No. 680, and in 1806, bought the house Jägerzeile 60 for 77,000 gulden.

The signatures on the 1796 marriage contract of Johann Manueli and Klara Steininger. Steininger's witness was the legendary businessman Nikolaus Smolenitz von Smolk (1765–1844). (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A10, 167/1817)

Johann Manueli, who by 1811 owned the "Kalzinirte Debreziner Soda-Fabrik", was also a business partner of Nikolaus Smolenitz von Smolk's soda factory in Gumpendorf (on 23 February 1797, he had been best man at Smolenitz von Smolk's wedding [Gumpendorf 13, p. 139f.]). In 1813, Manueli must have fallen on hard times, because in 1814 his name is suddenly missing from Anton Redl's Handlungs-Gremien und Fabriken Adressen Buch. By the time of his death on 26 March 1817, he was completely bankrupt and had to be supported by his friend and lessor Franz von Lacasse. A note in Manueli's Sperrs-Relation explains the reasons for his economic demise as follows:

It turns out, by the way, that according to the widow, the deceased had become so run-down because of misfortune and lawsuits that he owned no assets apart from his few clothes, and that especially the tasteful furniture is the property of the undersigned landlord Franz v Lacòsse.

The note in Johann Manueli's Sperrs-Relation concerning his deplorable situation at the time of his death. Manueli died in Kyro Nicolitz's house on the Jägerzeile. Nicolitz seems to have been a financier of Manueli and Lacasse. (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A2, 2247/1817)

Georg and Anton Stauffer decided not to continue business with the new owner and not to pay Klara Manueli a life annuity. On 4 May 1829, Johann Georg Stauffer and Manueli signed an "immerwährenden Gesellschafts-Auflösungsvertrag" (contract of perennial liquidation).

The signatures of Staufer and Klara Manueli ("als beding erklarte Erbin des Herrn Frantz edl v Lacasse") on their 1829 contract of liquidation. (A-Wsa, Merkantil- und Wechselgericht 2.3.2.A3.S 471)

Klara Manueli ("griech[ische] Handlsm[anns] Witwe") on an 1831 conscription sheet of Stadt 125 (together with Rosalia Grob and her children, a relative of Schubert's flame Therese Grob) (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Stadt 125/6r)

The sources provide no information as to when the Stauffers paid back their debt of 3,600 gulden Viennese currency. Klara Manueli died of lung failure on 8 July 1847, in the apartment of her nephew Franz Steininger at Stadt 817. No trace of her former business connection to the Stauffers can be found in her probate papers. In her will she left all her modest assets to her niece Barbara Steininger.

Klara Manueli's will dated and signed on 20 November 1843 (A-Wsa, Mag. ZG, A10, 521/1847)

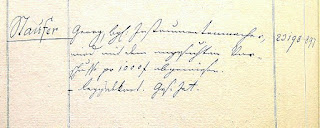

Beginning in 1829, the protocols pertaining to the Commercien- und Manufacturwesen (issues of commerce and manufacturing), as well as Steuerangelegenheiten (tax issues) of the Hauptregistratur bear witness to Stauffer's desperate attempts to get a loan from the Vienna magistrate and to have his income tax reduced. In 1829, Stauffer's application for a loan of 1000 gulden was turned down.

Stauffer's application for a loan is turned down in 1829 ("Staufer Georg, bgl: Instrumentenmacher wird mit dem angesuchten Vorschusse pr 1000 f abgewiesen."). (A-Wsa, HReg., Politica B1/363, Dep. M, p. 740)

In the same year, Stauffer applied to the magistrate for a tax rebate.

Stauffer applied for a tax rebate in 1829 ("Stauffer Georg bgl: Geigenmacher; um Erw[erbs] St[eue]r H[era]bs[etzung] Berichtsk[onzept] samt Beyl[agen]"). (A-Wsa, HReg., Politica B1/369, Dep. U, fol. 199)

In 1830, Stauffer again applied for an income tax rebate.

Stauffer's request for an income tax abatement in 1830 ("Stauffer

Georg bg. Geigenmacher wegen Erw[erbs] St[eue]r Nachsicht

Berichtskonz[ept] 1 Beil[age] Berichtsk[onzept]"). (A-Wsa, HReg., Politica B1/386,

Dep. U, fol. 161)

None of the files in the Hauptregistratur concerning Stauffer's various applications survives.

It is obvious that Johann Georg Stauffer and his son never really recovered from their business adventure and the financial obligations that resulted from the dissolution of "Staufer & Comp.". In 1833, Stauffer resigned from his craft and left the debt to be repaid by his son. Owing to his unbridled ingenuity and his total lack of business acumen, Stauffer never managed to run his workshop on a long-term profitable basis.

Was Christian Friedrich Martin Stauffer's Apprentice?

Christian Friedrich Martin, the founder of C.F. Martin & Company, was born on 31 January 1796 in Markneukirchen in the kingdom of Saxony. The Martin Company's current official history claims that "Christian Frederick took up the family craft at the early age of 15, when he left his hometown and traveled to Vienna to apprentice with Johann Stauffer, a renowned guitar maker".

A clip from the Martin & Co. timeline as of March 2014

According to the Martin family history, the claim that Martin learned with Stauffer is based on an alleged statement by a Markneukirchen wholesaler, who (supposedly in 1827) declared: "Christian Friedrich Martin, who has studied with the noted violin and

guitar maker Stauffer, has produced guitars which in point of quality

and appearance leave nothing to be desired and which mark him as a

distinguished craftsman." But this statement could already have been based on information provided by Martin, who certainly improved his business prospects in Saxony by professing himself as pupil of a celebrated Viennese luthier. Although Martin's alleged apprenticeship with Stauffer in Vienna has never been corroborated, it has been repeated as fact without any further proof in several books about the Martin Company and it also appears in the catalog of the current exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum. The identity of Stauffer's apprentices in the year 1811 is known, and Christian Friedrich Martin is not among them. On 2 January 1811, the title page of the Wiener Zeitung contained the following note:

The note in the Wiener Zeitung regarding Stauffer's and his apprentices' contribution to the Bancozettel-Tilgungsfonds. Hofmann only published a follow-up note from 13 February 1811 that does not list Stauffer's staff.

The local civil violin and lute maker Georg Stauffer has submitted a document to His Majesty in which he offered – in addition to his taxes – to voluntarily give ten percent of his total business revenue in 1811, without deduction of prior expenses to the I. & R. Bancozettel redemption fund. Spurred by this example his five apprentices: Johann Götz, Johann Buckschek, Franz Fink, Bernhard Enzensberger and Mathias Hametter also obliged themselves to give one gulden per week from their income for the same purpose.

There is no demonstrable connection between Martin and Stauffer, except for their mutual acquaintance with Franz Rzehaczek, and Martin's own claim that he and his fellow emigrant, the guitar builder Heinrich Schatz had trained with Stauffer. This assertion is also documented by guitar labels which Martin had printed in New York during the mid 1830s: "Martin & Schatz from Vienna pupils of the celebrated Stauffer". As far as we know, Martin did not chose his supposed teacher Stauffer as godfather for one of his children. On 25 April 1825, at St. Ulrich's, Martin married Ottilia Kühle, born on 7 October 1804 in Schottenfeld, daughter of the authorised machine carpenter and maker of pedal harps Carl Kühle and his wife Eleonore, née Hofbauer.

The entry concerning the baptism of Ottilia Kühle (spelled "Gille" and "Kille") on 7 October 1804 (Schottenfeld, Tom. 6, fol. 301).

Since February 1825, Christoph Friedrich Martin had been living in the house Spittelberg No. 95, "Saint Luke" (today Schrankgasse 10), but Martin is not listed in this house's conscription sheets. The address of Martin's bride was Spittelberg No. 98, "The Golden Lynx" (today Schrankgasse 4). Not surprisingly, Martin's best man was the instrument collector and violin expert Franz Rzehaczek. The marriage entry (which is a fair copy of the lost original) reads as follows:

62 / 4ter / Get.[raut] am 25ten April von Benedikt Lichtensteiner Pfarrer.Christian Friedrich Martin Instrumentenmacher, l.[edigen] St.[andes] geb.[oren] v. Marktneukirchen in Sachßen, des Johann Georg Martin Bürgers und Musik Instrumentenmachers, und der Eva Regina geb. Paulus beyd.[e] am Leben ehl.[icher] Sohn.

Spitlberg Nro 95. 2 Monath. / Ev.[angelischer] R.[eligion] 29 [Jahre] Taufschein gezeigt. Erlaubniß von Magistrat und von der Geburtsobrigkeit gebracht.

Ottilia Kühle l. St. geb. v. hier, des Carl Kühle, bef.[ugter] Maschin Tischler und der Eleonora geb. Hofbauer beyd: am Leben ehl. Tochter.

Spitlberg Nro 98. 20 [Jahre] Vater williget ein Karl Kühle

[Beystände] Franz Rzehaczek k.k. Hofconcipist Stadt Nro 846

Jos. Stabl k.k. Hofburgtheater Casse. Controlor Spitlberg Nro 134. (St. Ulrich, Tom. 37, 62/1825)

The entry concerning Christian Friedrich Martin's wedding on 25 April 1825 to Ottilia Kühle. In 2011, Erik Pierre Hofmann published this document, but his transcription is incomplete and flawed.

The names of the witnesses in Martin's marriage entry. Hofmann misread Rzehaczek as "Zehaczek" and turned the "k.k. Hofburgtheater Casse Controlor" Joseph Stabl into "Josef Rabl".

Carl Kühle

Christian Friedrich Martin's father-in-law Carl Kühle was born around 1773, in Auerstedt in Thuringia. He first settled in Vienna as carpenter in the suburb of Schottenfeld. At some time around 1820, he also lived in the house Spittelberg No. 95 which in 1825, was to be the home of his son-in-law Christian Friedrich Martin.

Carl Kühle ("Harpfenmacher v Auerstadt in Reich") and his family registered on an 1820 conscription sheet of the house Spittelberg 95. The years of birth of the daughters Ottilia and Josepha are wrong. They should read 1804 and 1808 (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Spittelberg 95/16r).

On 4 June 1821, Kühle was granted a patent for a new design of a pedal harp (Stephan Edler von Keeß: Beschreibung der Fabricate, welche in den Fabriken, Manufacturen und Gewerben des österreichischen Kaiserstaates erzeugt werden. Vienna: Wallishauser, 1823, p. 190) which had four holes on the back of the resonance box that led to a stronger tone of the instrument.

Kühle's invention was an economic failure and by 1824, he was totally broke. The legendary harpist Josephine Müllner-Gollenhofer (1768–1843) gave several charity concerts and collected 2,975 gulden in Viennese Currency for Kühle's benefit. Honoring Müllner-Gollenhofer's effort, on 12 June 1824, the journal Der Sammler published the following laudatory poem.

The description of Kühle's newly invented harp in Anton Ziegler's Adressen=Buch (Vienna: Anton Strauß, 1823)

Kühle's invention was an economic failure and by 1824, he was totally broke. The legendary harpist Josephine Müllner-Gollenhofer (1768–1843) gave several charity concerts and collected 2,975 gulden in Viennese Currency for Kühle's benefit. Honoring Müllner-Gollenhofer's effort, on 12 June 1824, the journal Der Sammler published the following laudatory poem.

Heinrich Schatz

Christian Friedrich Martin's colleague (or teacher?), the luthier Heinrich Schatz, who in 1833, together with Martin, emigrated to the United States, is still a somewhat enigmatic figure. Until now it was not even known if he ever visited Vienna. Like Martin, he does not appear in Rudolf Hopfner's 1999 book Wiener Musikinstrumentenmacher 1766 – 1900. Erik Pierre Hofmann writes: "There is no document known to us to prove that Schatz stayed in Vienna." Hofmann also claims that Martin left Vienna for Markneukirchen in 1826, one year after his wedding. Both assertions can be disproved. That Martin and his colleague Heinrich Schatz were still in Vienna in 1827, is proved by the baptism of Martin's daughter Emilie on 2 May 1827, at St. Ulrich's, with Heinrich Schatz serving as godfather.

The birth of Emilie Martin in Vienna in 1827 proves that the following information on the Martin & Co. timeline (as of March 2014) cannot be correct: "Christian Friedrich Martin, Jr. was born on October 2, 1825. [...] Shortly after the birth of their son, the young Martin family returned to Mark Neukirchen." The entry concerning the birth of Christian Friedrich Martin Jr. in Vienna has not yet been located. In any case, the child was neither baptized at St. Ulrich's nor the Piarist Church of Maria Treu. [Update: The information that Christian Frederick Martin Jr. was born on 2 October 1825, in the house Laimgrube 34 (St. Josef ob der Laimgrube 17, fol. 59), was published in 2018, in my article "The Godchildren of Emanuel and Eleonore Schikaneder". Martin's godfather was the luthier Christian Meinl.]

The entry concerning the baptism of Christian Friedrich Martin's daughter Emilie on 2 May 1827, in Vienna with Heinrich Schatz's autograph signature.

264 [Baptizans] Heinr[ich] Enderlemp Pfarr. Prov[isor]By that time, Martin had moved from Spittelberg 95 to Neubau 154 (today Stuckgasse 9).

[Monath May.] d[en] 2ten May

[Ort und Nr des Hauses] Neubau 154.

[Name des Getauften] Emilie geb.[oren] d[en] 27ten April vormit[ag] 1/4 11 Uhr.

[Weiblich] 1.

[Vaters Name und Condition oder Character] Christian Friedrich Martin Instrumentenmacher. Evang.[elischer] Rel.[igion] A.[ugsburger] Confes.[sion]

[Mutters Tauf= und Zunamen] Otilia des Karl Kühle bef.[ugten] Maschinen-Tischlers und der Eleonora geb.[orenen] Hofbauer Tochter. Kath[olischer] Rel[igion]

[Pathen] Heinrich Schatz Instrumentenmacher. A: C: und [im Nahmen ihrer?] Theresia Frank geprüfte Hebamme K.[ind]

[Anmerkungen.] L.[aut] Sch.[ein] getraut hier d[en] 25ten April [1]825. Heb.[amme] Frank Theres Spitlb.[erg] 126. (St. Ulrich Tom. 44, fol. 51)

The house Stuckgasse 9 (formerly Neubau 154), Christian Friedrich Martin's last known Viennese residence. Conscription records of this address only survive from after 1830.

The birth of Emilie Martin in Vienna in 1827 proves that the following information on the Martin & Co. timeline (as of March 2014) cannot be correct: "Christian Friedrich Martin, Jr. was born on October 2, 1825. [...] Shortly after the birth of their son, the young Martin family returned to Mark Neukirchen." The entry concerning the birth of Christian Friedrich Martin Jr. in Vienna has not yet been located. In any case, the child was neither baptized at St. Ulrich's nor the Piarist Church of Maria Treu. [Update: The information that Christian Frederick Martin Jr. was born on 2 October 1825, in the house Laimgrube 34 (St. Josef ob der Laimgrube 17, fol. 59), was published in 2018, in my article "The Godchildren of Emanuel and Eleonore Schikaneder". Martin's godfather was the luthier Christian Meinl.]

Stauffer Residences

Concerning Stauffer's addresses, it is not always possible to distinguish between the location of his apartments and his workshops. A number of Stauffer's residences are given in Hofmann's book, but Hofmann not only fails to provide their modern addresses, he also grossly misidentifies some of them. The house "An der Wien 132" was not Stadt 132, but Laimgrube 132 and Stauffer's address in 1814, "Seitzergasse neben der k.k. Ober-Polizey-Direkzion", was not the Seitzerhof Stadt 460 (last number 427), but the house on the other side of the police headquarters, Stadt 456 (last number 423). At one instance Hofmann even pretends to have checked sources which in actual fact he has not seen. He gives several conscription sheets as being relevant to Stauffer's addresses, but either their numbers are wrong or Stauffer's name does not appear on them. Here are some of Stauffer's Viennese residences in chronological order (what follows is not a complete list).

Laimgrube 169, "Zum Ungarischen König" ("The Hungarian King", today Mariahilfer Straße 11). Between 1803 and 1805, Johann Georg Stauffer moved his workshop from the inner city to the house Laimgrube 152 (last number 169), where his sons Anton and Alois were born. This house is significant, because in 1805, not only the court violinist Zeno Menzel (1757–1823) lived there, but in 1820, also the glover Martin Lanner (1771–1839) with his two children Joseph and Anna. Stauffer does not appear on this house's conscription sheets.

The house Mariahilfer Straße 11 today (built in the 1880s)

Stadt 413 (earlier number 446, today Schulhof 6 / Pariser Gasse 2), where Stauffer had his workshop between 1807 and 1813, which is documented by a guitar label from that time.

Stadt 423 (today Seitzergasse 2, torn down in 1874 or 1881), where Stauffer had his workshop in 1814. "Neben der k.k. Ober-Polizey-Direktion" does not refer to the Seitzerhof (as erroneously given by Hopfner and Hofmann), but to the house on the other side of the police headquarters.

Stauffer's 1814 guitar label referring to Stadt 423 (note the single f spelling)

Stadt 1006, "Zum Goldenen Löwen" ("The Golden Lion", today Krugerstraße 3). The Stauffer family lived there in 1811. This building was torn down in 1903.

The house Stadt 1006 where the Stauffer family lived in 1811. (A-Wn, EP 1144 B)

The Stauffer family listed on a conscription sheet of Stadt 1006. The apartment's previous tenant Johann Kurzrock (1792–1870) was a member of Franz Schubert's circle (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Stadt 1006/9v).

Laimgrube 177, "Zur Flucht nach Ägypten" ("The Flight into Egypt", today Mariahilfer Straße 4),

where Georg Stauffer's family lived at "4. Stiege, 1. Stock" between 1811 and 1821. This house is

significant, because in 1790, the clarinettist Johann Nepomuk Stadler lived there.

Laimgrube 177, "Zur Flucht nach Ägypten" (today Mariahilfer Straße 4)

The Stauffer family on an 1817 conscription sheet of Laimgrube 177 (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Laimgrube 177/12r)

Laimgrube 132, an der Wien, Obere Gestättengasse (today Luftbadgasse 5). Stauffer lived here in 1823, which is documented in part two of Franz Heinrich Böckh's book Merkwürdigkeiten der Haupt- und Residenz-Stadt Wien und ihrer nächsten Umgebungen and by an entry on a conscription sheet. That Stauffer moved there was probably caused by the fact that this building belonged to the Hessian piano builder Mathias Müller (1770–1844), who from 1819 on, lived at Leopoldstadt 502. Stauffer's apartment was later rented by the piano builder Joseph Knam (1790–1865) and the organ builder Franz Ullmann (1815–1892).

The house Laimgrube 132 (today Luftbadgasse 5) where Stauffer lived in 1823

The Stauffer family on a conscription sheet of Laimgrube 132, succeeded by the family of piano builder Joseph Anton Knam. Note that Anton Staufer is described as "Musikus v[om] Grund" (i.e. Laimgrube). (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Laimgrube 132/16v)

Stauffer's workshop at that time was located at Stadt 1064 (the "Wetzlar'sches Haus", today Plankengasse 2).

Staufer's addresses in Böckh's 1823 guidebook (vol. II, p. 145)

Wieden 1, the Freihaus auf der Wieden. In early 1825, Johann Georg Stauffer had his workshop in the city at the Klosterneuburger Stiftshof Stadt 1111 (today Plankengasse 6 and 7), while he lived in the Freihaus in the district of Wieden which is proved by two documents: first, there is Franz Staufer's application for the renewal of a passport to the (then) Russian town of Berdychiv:

Franz Staufer's prolongation on 18 February 1825 of a passport to "Berdycsow in Rußland". His address is given as "Wieden 1" i.e. the Freihaus auf der Wieden (A-Wsa, Passprotokoll B4/11, fol. 30).

The second document is a conscription sheet of the Freihaus listing the Stauffer family.

The family of Johann Georg Stauffer ("bürg. Geigenmacher v Weißgarber geb. seit 20t Junÿ [1]800") on a conscription sheet of the Freihaus from 1825. (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Wieden 1/281r)

Stadt 961, the hotel "Zur Ungarischen Krone" ("The Hungarian Crown", today Himmelpfortgasse 14), where Stauffer lived in January 1831, when he was sued by his tailor Friedrich Wendt for a debt of 38 fl 13 x. Stauffer was convicted in absentia, but the garnishment proved to be uncollectable. At that time Stauffer had his workshop at Stadt No. 785.

The hotel "Zur Ungarischen Krone" on the far left in 1899. This house, where Carl Maria von Weber resided in 1823, was torn down in 1902. (A-Wn, ST 400F)

The Stauffer family in 1830, in the house Stadt 961. Stauffer is misnamed "Ignatz" and his wife's place of birth is mistakenly given as "Dresden Sachsen". Anton Staufer "verwendet sich beym Geschäft des Vaters" ("is working in his father's shop") and from the entry in red ink on the right we learn that by 1831, Anton Staufer suffered from a "Saamenaderbruch" (i.e. a varicocele). This conscription sheet was put into the file belonging to Stadt 919 and later transferred back to Stadt 961 (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Stadt 961/21r).

Stadt 919 (today Weihburggasse 14) where in 1833, Johann Georg Stauffer lived with his son Anton.

The house Stadt 919 (today Weihburggasse 14)

Stauffer listed as having moved out to No. 919 on a conscription sheet of Stadt 961: "wohnt pro 834 No 919 in d. St[a]dt." ("is residing at Stadt 919 as of1834") (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Stadt 961/41r).

Anton Stauffer, listed in 1834, as tenant on a concription sheet of Stadt 919 with the reference "N° 961" (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Stadt 919/44r)

Leopoldstadt 510, "Zum Guten Hirt" ("The Good Shepherd", today Weintraubengasse 1). In the late 1830s, Stauffer and his wife moved to the house Leopoldstadt 510. In this house, which was located beside the Theater in der Leopoldstadt, and torn down in the 1960s, Stauffer must have made the acquaintance of his housemates Ferdinand Raimund and Johann Nestroy.

The house Leopoldstadt 510 where Stauffer and his wife lived in 1839. The house on the far left is the Carltheater. (A-Wn, ST 879F). The music publisher Johann Traeg the younger died in this house on 10 November 1839 (St. Johann Nepomuk 4, fol. 354).

Stauffer and his wife on a conscription sheet of Leopoldstadt 510. The note beside Stauffer's name refers to a passport that the couple received on 29 March 1839, for a sojourn in Hungary that lasted several years (A-Wsa, Konskriptionsamt, Leopoldstadt 510/28r).

After their return from Hungary, Stauffer and his wife, on 13 February 1845, moved into the Bürger-Versorgungshaus No. 572 in St. Marx.

The entry in the occupancy protocol of the St. Marx almshouse concerning Stauffer and his wife. Here we see that Anton Stauffer (residing at Stadt 1100) paid a monthly fee of eight kreuzer for his father who used an "eigenes Bett" (his own bed). (A-Wsa, Städtische Anstalten und Fonds, St. Marx, Standesprotokoll B6/2, fol. 176).

The entrance of the poorhouse St. Marx where Stauffer died in 1853 (A-Wn, ST 457F). As of 1857, this building housed Adolf Ignaz Mautner's St. Marx Brewery.

Labels in his latest instruments ("Landstrasse Nr. 572") show that even in the poorhouse Stauffer was still building guitars. On 31 January 1852, Josepha Stauffer died of "Gehirnerweichung" (softening of the brain).

The entry in the parish register concerning Josepha Stauffer's death (Pfarre Rennweg, Tom. 7, fol. 46)

Johann Georg Stauffer died on 24 January 1853, of "Lungenlähmung" (lung failure) and was buried three days later in the St. Marx Cemetery.

The entry concerning Johann Georg Stauffer's death (Pfarre Rennweg, Tom. 7, fol. 80)

Stauffer's Personality

Stauffer's application from December 1841 for a three-year prolongation of his passport to Hungary contains a description of his appearance:

Build: medium Face: oval Hair: black Eyes: brown Nose: proportioned Special features: none

The description of Stauffer's appearance in an entry on 30 December 1841, concerning the prolongation of a passport to Hungary. (A-Ws, Konskriptionsamt, B4/30, fol. 607)

There is also a fascinating document concerning Stauffer's personal character. When in 1823, in Pest, the luthier Peter Teufelsdorfer presented his "newly invented" version of a Guitarren-Violoncell, which was nothing else than a weak copy of Stauffer's Arpeggione that Teufelsdorfer called "Sentimental-Guitarre", Stauffer published an elaborate "Erklärung" (clarification) in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, mit besonderer Rücksicht auf den österreichischen Kaiserstaat.

The first two columns of Stauffer's statement against Peter Teufelsdorfer, which he published on 18 June 1823, in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, col. 389-92.

This amusing text is a masterpiece of irony and utterly contemptious mocking. Even if Stauffer commissioned somebody else to write this response, it beautifully demonstrates his sparkling mindset.

Obschon ich ein wahrer Freund von Erfindungen bin [...] so kann ich mich doch nicht überwinden, einer feinen Erfindung meinen Beyfall zu geben. [...] Als der hohe Rath von Indien beysammen sass und der edle Columbus das aufgegebene Kunststück, ein Ey auf dem spitzen Theile festzustellen, so naiv löste, da wussten freylich die andern alle, dass das eine leichte Sache sey. [...] Der dem grossen Lob nachkommende, hinkende Bothe, dass die Grösse des Pesther Locales daran müsse Schuld gewesen seyn, dass der Effect nicht eben der beste gewesen war, beweist aber noch mehr, dass es nicht eben leicht ist, solche in den Zeitungen beschriebene Erfindungen gleich noch einmahl nachzuerfinden, denn dazu gehört mehr, als der blosse fromme, edle Wille. In einem ähnlichen Falle befand sich jener Beobachter eines Herrn, der sich rasirte. Er stand im Winkel, und sahe die Leichtigkeit, mit welcher dieser das schöne, blanke Messer über's Gesicht fahren liess, und den Bart wegnahm, und fühlte ein Lüstchen bey seiner Entfernung, das Ding nachzumachen – schnitt sich aber in die Nase. [...][translation:]

Although I am a true friend of inventions [...] I cannot bring myself to applaud a fine invention that is attributed to the citizen of Pesth, Mr. Teufelsdorfer. [...] When the high council of India sat together, and the noble Columbus so naively solved the task of firmly putting an egg on its tip, all the others surely knew that this was an easy thing to do. [...] The limping messenger that followed the great praise, claiming that the size of the venue in Pesth must have been the reason that the effect was not the best, once again proves that it is not that easy to reinvent an invention that has been described in the papers, because this needs more than just the good and noble will. The observer of a gentleman, who was shaving himself, was in a similar case. Standing in a corner, he saw the ease in which this man had the pretty and shiny knife go across his face, taking away the beard, and from a distance he felt a small desire to do the same – but cut himself in the nose. [...]

Future Research Tasks

Concerning Stauffer and his colleagues, there are three collections of sources that have so far escaped the attention of researchers: First, there are the files related to the Privilegien (NÖ Reg, A1) in the holdings of the Lower Austrian Government in the Niederösterreichisches Landesarchiv (Provincial Archives of Lower Austria). These documents have never been scrutinized by historians of violin making. Second, there are the files of the civil court of the Vienna City Council. In 1831, Stauffer was flooded with lawsuits from his creditors. I have only just begun browsing the files pertaining to these court procedings, most of which do not survive. Third, there are the files of the Hauptregistratur of the Vienna Magistrate which have barely been touched by Stauffer researchers. Especially the holdings covering the Commercien- und Manufacturwesen (commercial and manufacturing issues) should by systematically searched for traces of the professional activity of Christian Friedrich Martin. I think that the Martin Company should initiate a research assignment to shed more light on Martin's formative early years in Vienna.

Johann Georg Stauffer's autograph signature. Although he wrote his name with a single f, the spelling of his surname is completely variable. He frequently used labels with the spelling "Staufer" on which he put a seal bearing "Stauffer" (and vice versa). One thing however (as demonstrated by Hofmann in his book) should never be done: to "homogenize" Stauf(f)er's name by wilfully adding a second f to his name in a literal transcription of an archival document.

© Dr. Michael Lorenz 2014. All rights reserved.

Updated: 16 August 2024

Updated: 16 August 2024

.JPG)

.jpg)

+Weihburggasse14.JPG)