This statement proves that at some point Pincherle must have seen (the by then unpublished) folio 177r of the original 1741 Bahrleihbuch. It also proves that he had only a small notion of what the words in this book really mean. Robbins Landon's misunderstanding, which consequently was to appear all over the Haydn literature, originates from this passage in Pincherle's book. A "Kleingleuth" was not a "pauper's peal of bells". 2 florins 36 kreuzer was a week's salary of a well-paid manservant. The commissioning of a holy mass cost 30 kreuzer in Vienna, a price that did not change for at least two centuries. The six "Kuttenbuben" were not even boys, but men in cowls and they surely did not sing. The "nobleman", who according to Pincherle was buried the day before Vivaldi, was actually a noblewoman: the widow Maria Agnes von Feichtenberg who had died of "Wassersucht" (dropsy) on 26 July 1741, at the "Goldener Hirsch", on the Fleischmarkt.

The expenses, which totalled 19 florins and 45 kreutzers, were kept to the minimum. If Mozart's burial 50 years later was that of a pauper, Vivaldi's deserves that sad epithet equally. (Talbot 1993, p. 69)

In his book

Vivaldi: Voice of the Baroque (London: Thames & Hudson, 1993), Robbins Landon expressed a similar judgement: "He was entitled, only to the Kleingeläut, or the pauper's peal of bells, costing two florins and thirty-six kreuzer." In his Vivaldi article in

The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Talbot states: "[...] he was given a pauper's burial on the latter day at the Hospital Burial Ground (Spittaler Gottesacker)." (

New Grove, Vol. 26, p. 820). In the other prominent music encyclopedia

Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, Karl Keller tells us that Vivaldi was buried "mit einfachster Zeremonie" (with the simplest ceremony) (

MGG, Vol. 17, col. 89). None of the authors who wrote books about Vivaldi ever scrutinized the Viennese sources to actually figure out how obsequies at the time of Vivaldi's death were performed in Vienna.

Obsequies at St. Stephen's Cathedral Around 1740

For someone, who for about fifteen years has been studying the Bahrleihbücher of St. Stephen's (which survive from 1662 into the 1830s, with lots of gaps in the late years), Vivaldi's entry leaves no room for ambiguity or misunderstandings. It refers to a regular funeral ceremony with a "Kleingleuth", i.e. the peal of the small bell on the west section of the Cathedral's roof. At the time of Vivaldi's death, there were four kinds of peals of bells at St. Stephen's (fl stands for florins, x for kreuzer):

- "Großgleuth" at 9 fl 41 x (or ordinari at 19 fl 22 x)

- "Fürstengleuth" at 4 fl 20 x

- "Bürgergleuth" at 3 fl 45 x

- "Kleingleuth" at 2 fl 36 x

These four classes of "Gleuth" actually referred to four different bells on the cathedral. On rare occasions, at a price of 50 gulden, the "große Glocke" (the old

Pummerin) was pealed, but this was not a separate class, it was an additional luxury which was only available for members of the

Landstände (i.e. the noble members of the

Niederösterreichische Landtafel). Of course, combinations were also possible: after a "Großgleuth" at the beginning of the ceremony, there could be an additional "Fürstengleuth" right before the Requiem prayer ("zum Requiem vorgeleuth"). There were bells of many other churches that could be pealed on demand on the occasion of funerals at St. Stephen's: the

Magdalene Chapel beside the Cathedral,

St. Peter's Church, the

Minoritenkirche, the

Bürgerspitalskirche, the

Ruprechtskirche, "

Unser Lieben Frauen Stiegen", St. Nicola,

St. Salvator and the "

Deutsches Hauß". Furthermore, there were bells of chapels in privately owned houses all over the city that could be pealed for funerals, such as the ones in the

Freisingerhof, the

Gundelhof, the

Seitzerhof, and the

Johanneshof. Many funerals

, like those of small children and really poor people, had no peal of bells at all.

A funeral without a peal of bells: Georg Planckh being buried on 5 May 1740, in the "Spitaller Gottsacker" (A-Wd, BLB 1740, fol. 119r)

There were a number of general rules and customs concerning funerals at the Cathedral that can be figured out by studying the eighteenth-century

Bahrleihbücher of St. Stephen's. The "Kleingleuth" was not part of a pauper's burial. Real pauper's burials were "gratis".

The "gratis" burial of Giulio Cesare Birravri on 30 May 1741, in the cemetery of St. Stephen's (A-Wd, BLB 1741, fol. 131r). This entry proves that poor adult foreigners were also buried in the "St. Ste[phans] Freind Hof", i.e. the cemetery around the Cathedral.

The "Kleingleuth" was the standard procedure for the funeral ceremony of adult citizens. Court officials, civil servants, civil craftsmen, and secular priests all received this kind of peal of bells. Karl Heller's claim that "the sum of nineteen florins and forty-five kreutzers would have been sufficient for only the simplest of ceremonies" (Heller 1997, p. 265) is simply false.

The entry concerning the funeral of the "Königlicher Laufer" (Royal footman) Lucrezio Bonno on 8 April 1742, which proceeded exactly like Vivaldi's (A-Wd, BLB 1742, fol. 95r). Bonno (born in 1683 in Pralboino) was the father of Hofkapellmeister Joseph Bonno (1711–1788). Bonno's first name was not Giuseppe (as given on Wikipedia and in the recent Mozart literature), but expressedly "Joseph Johann Baptist2, because his godfather was Joseph I. Contrary to the date given in the literature, Joseph Bonno was born on 30 January 1711 (A-Wd, Tom. 54, fol. 397r).

The entry concerning the funeral of the secular priest Joseph Russignol on 1 February 1741, in the "Schwarz Spanier" cemetery on the Alsergrund (A-Wd, BLB 1741, fol. 24r). Except for the Kelch (chalice), which was put on the bier, this funeral resembled Vivaldi's.

The entry concerning the funeral of the composer Carlo Agostino Badia on 25 September 1738 (A-Wd, BLB 1738, fol. 254r). Note that, owing to the lack of lanterns, the funeral of the "Kaÿs: Hof- und Cammer-Musicus" was two gulden cheaper than Vivaldi's, suggesting that the lanterns at Vivaldi's funeral were a dispensible luxury.

The entry concerning the funeral on 9 Desember 1741, of the court musician (bass singer) Marco Antonio Berti (A-Wd, BLB 1741, fol. 269v). Because Berti was buried in the cemetery around the Cathedral, his expenses included the ringing of the cemetery bell and the fee for the gravedigger which added 66 kreuzer to the costs of Vivaldi's ceremony.

The class of peal of bells was not the decisive factor concerning the costs of funeral ceremonies at the cathedral. The most expensive items – apart from the very high costs of tombs in the cathedral's crypt which sometimes came with the additional wage of a master builder – were always the services of qualified people, such as the presence of a high number of additional clergymen (

Curaten and

Canonici). One

Canonicus cost three gulden, a curate two, an

accolidus (acolyte) 50 kreuzer. The Kuttenbuben only cost nine kreuzer apiece, the better

Minestranten cost one gulden each. High fees had to be paid for musicians (in variable numbers) who actually sang a

Miserere and one or several "Motteten" (an exception being the obsequies of prominent musicians such as

Antonio Caldara for whom, on 29 December 1736, his colleagues performed "gratis"). Even more expensive was the participation of instrumentalists (for 15 gulden) who accompanied the singing "mit Sartin" (also spelled "mit Sardin") or "Sartindl" (with muted trumpets or trombones). The most expensive musical service available was the performance of an actual Requiem which required additional musicians for at least 15, or up to 24 gulden. Sometimes the conduct was followed by a group of poor people from various poorhouses, such as the "

Nepomuceni Spitall" on the Landstraße or the poorhouse in the Alstergasse, who received alms from the attendants and the clergy. This was an important additional income for the poor and this custom was observed in Vienna into the nineteenth century (on its way from the Alsergrund to Währing, Beethoven's coffin was followed by inmates of the "

Versorgungshaus am Alserbach" who got paid for this service). Sometimes the bier was also accompanied by regular people who are listed as

Steuerdiener (tax payers) in the Bahrleihbuch.

A group of poor people, following the bier of Georg Gaber, a law student, who was buried on 23 December 1741, on the "Spitaller Gottsacker": "Mitgang. 12. paar arme Leüth auß Nep:[omuceni] Spitall 12. paar auß d[er] alstergass[en] [Gleuth] Paulaner und Francis:[caner]. Pelican" (A-Wd, BLB 1741, fol. 280r).

What follows are several examples of expensive eighteenth-century funerals at St. Stephen's Cathedral.

The entry concerning the exequies of the architect Joseph Emanuel Johann Fischer von Erlach in the evening of 29 June 1742 (A-Wd, BLB 1742, fol. 173v and 174r). Prominent people often received a Nachtbegräbnüß (night funeral). Note the five altars which were put up on the following day and the additional "gleuth" at "[St.] Magdalena, Bürger Spitall" and the "Johannes Hof".

The first part of the entry concerning the funeral on 10 January 1726, of Carlo Agostino Badia's first wife, the singer Anna Maria Badia, née Lisi (A-Wd, BLB 1726, fol. 7r), whom Badia had married on 18 October 1700 (A-Wd, Tom. 34, pag. 710). Again, the grave in the crypt was the most expensive item. The last item are "12 stiell" (12 chairs). Note that the song "[Der] grimmige Todt" could also be accompanied by muted trumpets or trombones ("mit Sartindln"). When Johann Steinecker tried to transcribe this entry for his 1993 dissertation Die Opern und Serenate von Carlo Agostino Badia (supervised by Herbert Seifert), he could not figure out the meaning of the note "grimmiger Todt mit Sartindln" and transcribed it as "gereinigte Tote mit Sortinol", as if "Sortinol" was some kind of disinfectant for corpses. This is one of the all-time funniest transcription mishaps in Viennese historical musicology. Several gravely bungled passages in Steinecker's dissertation prove that his supervisor never read the thesis.

The obsequies for Princess Maria Theresia von Auersperg, née von Rappach, on 21 January 1741, with "VorLeithen" (a preceding peal), two peals of the Pummerin ("gar grosse glocken") on two separate days, and a double ("ordinari") "grossgleüth". This was not a a funeral, but only the consecration of the Princess whose body, on 23 January 1741, was transferred to Garsten where it was buried in the crypt of the monastery (A-Wd, BLB 1741, fol. 16r).

The entry concerning the exequies of the merchant Joseph Jenamy on 12 November 1740 (A-Wd, BLB 1740, fol. 259). The list of expenses included a "Fürstengleuth" and the already known expensive grave in the crypt. Here we see that the song "Der grimmige Todt" was also performed without brass and (in addition to the Miserere for six gulden) had to be paid extra. The external bells included St. Magdalene's, St. Peter's Church, and St. George's Chapel in the Freisingerhof. Joseph Jenamy (b. 1686 in Saint Nicolas de Véroce) was a great-uncle of Nikolaus Joseph Jenamy (1747–1819) who, in 1768, married Louise Victoire Noverre (1749–1812), the dedicatee of Mozart's piano concerto K. 271.

The most expensive funeral in the Bahrleihbuch of 1741 is that of Johann Caspar Joseph Kolb von Kollenburg, "Weÿl[and] der K.K. M[ajestät] Unter Stabelmaister" (deputy staff holder of His late I. & R. Majesty

Charles VI), which cost 195 gulden and 16 kreuzer (A-Wd, BLB 1741, fol. 10v and 11r). It included a Großgleuth, a tomb in the crypt, a Requiem with Fürstengleuth, 30 Kuttenbuben, and five altars.

The mysterious "Pelican" that appears at the end of the expenses for Vivaldi's funeral and which previous authors either ignored or left uncommented, was a picture of a pelican as a Christian symbol that was put on the bier.

A pelican reviving her young with blood from her own breast (NL-DHmw, 10 B 25, fol. 32r)

Because the

Physiologus claimed that the pelican provides its own blood to its young by wounding its own breast when no other food is available, this bird became a symbol of the Passion of Christ and the Eucharist.

There were several pictures that could be put on the bier at St. Stephen's: pictures of St. Sebastian, St. John of Nepomuk, the Good Sheperd,

Todtangst (Agony of Christ), the Holy Rosary, the Holy Trinity, one of a

Bruderschaft (confraternity), a

Dominicaner, a

Carmeliter, and two (unspecified) "Franciscaner Bilter". But the pelican was by far the most frequently used. Sometimes, a devotional scapular was also put on the bier. The custom of displaying these pictures may go back far into the seventeenth century, but it is documented in a Bahrleihbuch for the first time only in 1682.

The final passage of the entry in the Bahrleihbuch concerning the funeral of Catharina Regina Thenig on 30 December 1682: "Seint mitgangen Kaÿ:[serliche] Spitall:[er] und Franscis: Gleüth beÿ St: Maria Magd: Bildter: Todtangst und Francisc." ("on the bier the pictures of the Agony of Christ and the Franciscans") (A-Wd, BLB 1682, fol. 171v).

The final passage of the entry concerning the funeral of the mason Adam Häringsleben on 12 Januar 1683: "Haben tragen 8 Steür diener seint mitgang[en] Kaÿ:[serliche] Spitäller Francisc: Dominic: und Minorit[en] Gleüth S:[ancta] Maria M[a]gd: S. Georgj S: Petri auf d[er] Pahr Pelican und St. Sebastiani Bildt." ("on the bier the pictures of the pelican and St. Sebastian") (A-Wd, BLB 1683, fol. 3v).

The final note of the entry concerning the funeral of Mathias Napert on 5 May 1740: "Mitgang 12. paar arme Leüth auß Nep[omuceni] Spitall 12. paar auß d[er] Alstergass[en] Franciscaner, Domin:[icaner] gleüth. Magdalena, Bilder Pelican, Rosen Cr:[antz] guten Hürten." ("pictures: pelican, rosary and Good Sheperd") (A-Wd, BLB 1740, fol. 118v).

The four categories of "Gleuth" existed until March 1751, when an Imperial edict replaced them with four "Classen". The prices of the peals in these classes were reduced to (from 1st to 4th class) seven, four, three, and one gulden. These classes could be subdivided into rubrics – mostly for the burials of children – but to delve deeper into the intricacies of this new system would lead too far. The first funeral ceremony at the Cathedral, which was accounted according to the new regulation, took place on 3 March 1751.

A clip from the entry concerning the funeral of the baby girl Magdalena Krumbschnabel on 3 March 1751: "Die Erste Begräbnuß nach de[m] Neüe[n] Patent. 2te Class Rubrica Tertia" ("The first burial according to the new edict. Second class third rubric [a child between one and seven years]") (A-Wd, BLB 1751, fol. 38v)

It has been suggested in the literature that Vivaldi may already have died on 26 or 27 July. But after closely comparing the official death register of the Vienna Magistrate (the

Totenbeschauprotokoll) with the 1741 Bahrleihbuch of St. Stephen's, I came to the conclusion that during the summer, people in Vienna were always buried the very same day they died. Especially interesting – although not particularly surprising – is the fact that there are a number of deaths recorded in the Bahrleihbuch that are missing in the

Totenbeschauprotokoll. The fact that Vivaldi was buried in a cemetery which was traditionally called "Armesünder-Gottesacker" (cemetery of the executed) has sometimes been explained with the composer's status as poor foreigner, who had no civil rights, because he was not a citizen of the Austrian monarchy. This hypothesis is false. It was a complete coincidence that Vivaldi was buried on the Wieden, because the records show that in the eighteenth century the dead were buried in whatever cemetery at the moment could provide space. Apart from the Cathedral's crypt (where the graves were expensive), the following burial sites were used for people who were consecrated at St. Stephen's at that time – regardless of their age, wealth or nationality: the cemetery of St. Stephen's (surrounding the Cathedral), the "Spitaller Gottesacker" on the Wieden, the cemetery of

St. Nikolai ("auf die Landstraß"), the crypt of the

convent church of the

Trinitarian Order and the "Montserrater Gottesacker"on the Alsergrund ("zu den Schwarzspaniern"), the crypts of

St. Michael's Church, the

Minorites Church and the

Augustinian Church, and the monastery church of

St. Nikola on the Singerstraße. The fact that Vivaldi was buried in an own grave at a relatively high cost of two gulden makes the fact that his funeral has repeatedly been described as that "of a pauper" even more bizarre.

Back to Haydn

The spark of wishful thinking concerning Vivaldi's funeral jumped to Haydn scholarship when H. C. Robbins Landon published his five-volume standard work Haydn: Chronicle and Works. Robbins Landon, of course, immediately fell in love with the idea of choirboys in 1741 which were nothing but Kendall's mistranslation of Pincherle's mistranslation of the original word "Kuttenbuben". In the first volume (p. 58) of his Haydn chronicle, Robbins Landon went so far as to even quote from Kendall's Vivaldi book.

"It seems almost certain." Does it? In his 1993 book Vivaldi: Voice of the Baroque, Robbins Landon (providing a wrong folio number for the Bahrleihbuch entry) again rhapsodized on one of his most beloved bit of trivia:

There were six pall-bearers and six choirboys from the parish church where Vivaldi died, which happened to be St. Stephen's Cathedral. The six members of the Cantorei of St. Stephen's included the young Joseph Haydn, who was thus probably one of the few to witness the demise of this great composer, now a pauper and already forgotten, placed, like Mozart half a century later, in an ignominious and anonymous grave somewhere under the great capital city of the Austrian Monarchy. (Robbins Landon, Vivaldi, p. 166)

From the countless books about Haydn that present Robbins Landon's idea as proven fact, I want to point out Hans-Josef Irmen's Joseph Haydn Leben und Werk (Vienna: Böhlau, 2007) where the information that Haydn sang at Vivaldi's funeral is even attributed to Pohl ("and others"[sic!]): "Pohl u.a. berichten, daß der junge Haydn bei den Exequien für Vivaldi mitgewirkt habe." (Irmen, p. 335). Of course, Carl Ferdinand Pohl (1819–1887) reports no such thing in his biography of Haydn. Pohl did not even know that Vivaldi had died in Vienna.

It is amazing to see how the probability of this romantic scenario is suddenly destroyed by having seen all the above entries from the eighteenth-century Bahrleihbücher. From 1715 on, the Cantorei of St. Stephen's employed six Capellknaben (choirboys). The documents presented above show that it was a mere coincidence that exactly six Kuttenbuben attended Vivaldi's funeral. And yet, this exact number – the number of Capellknaben at the Cantorei – played a major role in the misunderstanding that led to the metamorphosis of these Kuttenbuben into choirboys.

Capellknaben and Kuttenbuben

Haydn was accepted into the Cantorei of St. Stephen's Cathedral in 1740. Since Kapellmeister

Reutter was in a position to only pick the most talented choirboys, Haydn's recruitment was a big privilege and a stroke of luck for the country boy. Haydn lived together with the other choirboys in the building of the Cantorei which was administered by the municipal Kirchenmeisteramt (i.e. the City of Vienna). The administration of the Cathedral and its music was traditionally subordinate to the Vienna Magistrate, which is the reason that Mozart, when in 1791 he applied for an adjunct postion at the cathedral, submitted his application to the municipal authorities. The so-called

Kirchenmeisteramtsrechungen (ledgers of the church administrator of the Vienna Magistrate) provide detailed information about the organisation of the Cathedral and its employees. They show that the records of expenses for the regular staff ("Außgaab auf ordinarÿ Besoldung", i.e. expenses for ordinary salaries) were strictly separated from the expenses for the musicians of the Cantorei.

The beginning of the list of expenses ("Außgaab. Auf die Cantoreÿ beÿ St. Stephann")

for nine months for the Cantorei of St. Stephen's in the 1742

Kirchenmeisteramtsrechnung (A-Wsa, Handschriften, A 41.24, fol. 79r).

In 1741, the Kirchenmeister (church administrator) was Claudius

Jenamy (1702–1776), a nephew of the abovementioned merchant Joseph Jenamy. Today the eighteenth-century Kirchenmeisteramtsrechnungen are held by

three different archives: the Vienna Municipal Archives, the Vienna

Diözesanarchiv, and the Domarchiv.

In 1742, the choir at St. Stephen's Cathedral consisted of the following musicians:

Kapellmeister Georg von Reutter

Six Capellknaben

Nine Vocalisten

Extra-Vocalisten (whose number varied according to requirements)

Subcantor Adam Gegenbauer

The organist at that time was Anton Neckh who in 1736 had succeeded Reutter's son Karl on this post. Georg von Reutter's annual salary consisted of 300 gulden Gebühr (salary), plus 24 gulden Kleÿdergeld (clothing allowance). For the boarding of the six Capellknaben (among them Joseph Haydn) Reutter received an additional sum of 1,200 gulden plus 75 gulden Instructionsgeld (teaching fee). Each of the nine Vocalisten received an annual salary of 130 gulden plus an annual Choraladjutum (choral subsidy) of 26 gulden 60 kreuzer per capita. In addition to that they were also paid one gulden "Rorate Geld" plus (at least in 1742) one gulden forty kreuzer for substituting for dismissed choirboys.

Only two Kuttenbuben were permanently employed at the Cathedral. In 1742, they were assisted by an "Extra Jung" (extra boy). The other Kuttenbuben worked freelance for a fee of nine kreuzer for every funeral which added up to a nice income of about five gulden a month. This relatively high income (and the income of the permanently employed Kuttenbuben) are proof that those "Buben" were not boys at all, but adult men who were majors (above 24 years of age). The term "Kuttenbuben" had originated in the middle ages and was still applied to men dressed in cowls centuries later. The two regular Kuttenbuben were members of the ordinary staff and their salary was filed under the "ordinarÿ Besoldung". Among the employees that are listed together with the Kuttenbuben were the Bahrleiher Johann Leydl, the Capelldiener at the cemetery "vor dem Schottenthor" Bartholome Kießling, and the two church servants and "Preinglöckler" (the ringers of the prime bell). In addition to their individual annual salary of sixty gulden, each of the two regular Kuttenbuben also received five gulden for their service during the litany for the Court. The "Extra Jung" Geusgruber was paid 50 gulden a year. The two items in the 1742 Kirchenmeisteramtsrechnung pertaining to the salaries of the three Kuttenbuben, read as follows:

147:/ Denen 2. Kutten Jungen Dobraletnig und Vogl ihr gebühr von 1. April bis lezten Xber 742. auf 3/4. Jahr lauth N° 147. vergüthet . . . . 90 .––

148:/ Dem Extra Jung Michael Geusgruber sein gebühr von 1. April bis lezten Xbr 742. auf 3/4. Jahr inhalt N:° 148. entrichtet mit . . . . . . . . 37 " 30.

The entries concerning the salaries of the Cathedral's three "Kutten Jungen" Dobraletnig, Vogl and Geusgruber between 1 April and 31 December 1742 (A-Wsa, Handschriften, A 41.24, fol. 77v and 78r)

The overall expenses of the Kirchenmeisteramt in 1742 amounted to 20,255 gulden and half a kreuzer. The surplus in that year was 2,722 gulden and 29 kreuzer.

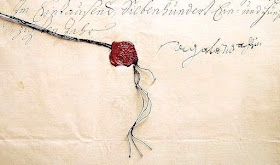

Claudius Jenamy's seal and signature in the 1742 Kirchenmeisteramtsrechnung of St. Stephen's

- Vivaldi's funeral ceremony on 28 July 1741, at St. Stephen's corresponded to that of ordinary Viennese citizens. Because the performance of music was not ordered and paid, no music was performed at this ceremony.

- To have musicians sing at a funeral at St. Stephen's in 1741, one had to pay at least six gulden for the performance of the song "Der grimmig Tod". A performance of a motet was even more expensive, especially if it was accompanied "mit Sardin" (i.e. with muted trumpets or trombones).

- The Kuttenbuben who were present at Vivaldi's exequies did not sing. They just stood at the altar and folded their hands in silence. They were not choirboys of the Cantorei, but members of the ordinary staff of the Cathedral. There was a strict organizational separation between the ordinary employees and the musicians of the Cathedral.

- Joseph Haydn had nothing to do with Vivaldi's obsequies. The mistaken assumption that choirboys were present at this ceremony originated with Marc Pincherle, who in 1948, translated the entry "6 Kuttenbuben" in the original source with "six enfants de chœur". After Alan Kendall, in 1978, had turned these "enfants de chœur" into "choirboys", Robbins Landon could not resist the appeal of this scenario and presented Haydn's singing at Vivaldi's exequies as a fact. It is a myth.

Despite repeated statements in the literature that the chances are slim of finding unknown sources concerning Vivaldi's final stay in Vienna, research on this topic is far from finished. It has only just begun.