Mozart had more immediate problems. He was known to be a Freemason and the French revolution had been fostered by French Freemasons who were in contact with their Viennese brethren. King[sic!] Leopold's secret police were well informed about the Lodges in Vienna and soon those connected with Freemasonry were discharged from their government posts.

The Vienna that Constanze encountered was unlike any other city in Europe. The population was so homogeneously united that only the epithet 'Viennese' fits its description. There was no question of 'nationality' as such among the inhabitants of Vienna, where Magyars, Bohemians, Slovaks and Slovenes, Germans, Italians and Poles rubbed shoulders in good humour. (p. 23)

The modest sum of 31 kreutzer would purchase a meal consisting of two meat dishes, soup, vegetables and unlimited bread with a litre[!] of wine. Because people were generous, even industrious citizens accepted the fact that some individuals might prefer begging to working, extreme poverty was practically nonexistent and those who made begging their profession often profited handsomely by it. (p. 23)

In an amazing display of ill-will Leopold Mozart accused Constanze of being a slut.

Mozart had many opportunities to gamble. Mozart's concerts at the Mehlgrube Casino were always followed by gambling tables being set up to allow the aristocracy to participate in their favorite sport. [...] Gambling was also endemic in Salzburg.

Casanova was an inveterate gambler who could never resist tempting his friends with a game of cards and it would not be inconceivable that Mozart lost considerable sums to him." (p. 85)

Franz II lived through this period as though in a dream, occupying himself with gardening, attending to his family and walking through the streets of Vienna dressed as just another burgher enjoying a bit of window shopping.

- That Joseph Lange signed a document "which bound him to grant his widowed mother-in-law an annual income of 700 ducats" (p. 23) is, of course, false. Lange promised to pay Cäcilia Weber 700 gulden which is less than a quarter of the sum given by Selby. That at the time of her wedding, Aloysia Weber was already pregnant is still an unproven assumption.

- That Gottfried van Swieten was "dismissed from the Imperial Service on suspicion of participating in the Freemasons' conspiracy of 1791" (p. 35) is a piece of gross misinformation that Robbins Landon presented in his book Mozart: The Golden Years. There was no "Freemasons' conspiracy of 1791". Van Swieten was dismissed by the Emperor "in good grace", because of their differing views concerning the universities' role in science and the freedom of education which was part of van Swieten's political concept.

- Like many amateur Mozart researchers, Selby mixes up the family of Adam Isaac Arnsteiner (1721–1785) with that of his daughter-in-law Fanny Arnstein. Fanny Arnstein did not "occupy the house at Graben No. 1175" (p. 35), her father-in-law Arnsteiner lived there as subtenant on the second floor.

- "Johann Thorwart was an altogether unpleasant and unsavory character". We have absolutely no documentary information concerning Thorwart's character. Selby is just jealous of him and picks her negative judgement out of thin air.

- Selby is unable to let go of the story regarding the music supposedly performed at Mozart's wedding dinner: "During the dinner Constanze was surprised by the unexpected performance of Mozart's Serenade in B-flat (K. 361)." (p. 40). This alleged performance is a myth which may have been caused by a sentence that was willfully added into one of Mozart's letters in Nissen's Mozart biography. There is absolutely no documentary evidence to support it.

- On p. 50 Selby claims that, on the occasion of the christening of Mozart's first child Raimund Leopold, on 17 June 1783, "Baron Wetzlar could not be present due to the death of his father". What looks like very educated information, is based on pure fantasy. Wetzlar's father Karl Abraham Wetzlar von Plankenstern only died on 3 September 1799 (Wiener Zeitung, 11 September 1799, p. 3063).

- The information that "Neustift suburb No. 250 is now Lerchenfelder Straße[sic!] No. 65" (p. 52) is false. As Hans Rotter published in 1925, and as I have explained on this blog, it is Mariahilfer Straße 94.

- That Mozart "composed the two duets for violin and viola for Michael Haydn [...] who was ill (supposedly due to heavy drinking)" (p. 53) is a fairy tale that has been debunked by Mozart scholarship a long time ago. It should really not reappear in a book released by a publishing house that calls itself Wissenschaftsverlag.

- Maynard Solomon's estimates concerning Mozart's income, which Selby copied into her book, are based on speculation. They have absolutely no basis in archival sources.

- "The banns for their marriage were read at the Theatines Chappel." (p. 39) No, they were not. Everybody who has seen Mozart's marriage entry knows that he and Constanze were exempt from the three readings of the banns. Furthermore, no banns were ever read at this chapel, because it was not a parish church. Mozart and his bride visited this chapel to go to confession and to get the "Beichtzettel" (certificates of confession) which they needed for the wedding.

- "After Lodge meetings, Mozart would join his brother Freemasons at the Cafe Jüngling, whose owner, Johann Jüngling belonged to the Lodge 'Zur neugekrönten Hoffnung'. There the men would sit down to dinner after which they gambled well into the early morning." (p. 63). There was no "Cafe Jüngling" in 1785, because Johann Jüngling (1762–1835) became the owner of this coffee house only in 1791. There was also no gambling at this Cafe. The whole scenario of this supposed "Freemasons' Casino" is the product of one of Selby's countless brain bubbles, obviously triggered by abysmally flawed secondary literature.

- The "ballet story" concerning Le nozze di Figaro is nice, but it has been shown ages ago that it is purely fictional. There is no documentary confirmation that dancers were hired for the complete production of Figaro in 1786.

- Franz de Paula Hofer's annual salary in 1788 at St. Stephen's Cathedral was 25 gulden, but (just like another writer, who in her new book calls Hofer a "penniless violinist") Selby is unaware of the fact that Hofer was a court musician and held several well-paid jobs simultaneously. Why should Josepha Weber have married a poor church mouse? At the time of his death, Hofer was making 360 gulden a year at the Court and 100 gulden at St. Stephen's, and he had additional jobs in other churches. Selby's claim (p. 142) that he "left Josepha and their daughter burdened with enormous debts" is simply false. Franz Hofer's debts were managable, because, unlike Mozart, he had actually joined the Tonkünstler-Sozietät to secure the livelihood of his widow and child. Between the death of her first husband on 14 June 1796, and her second marriage on 23 December 1797, Josepha Hofer was paid a pension from the Tonkünstler-Sozietät which, according to § 15 of the society's regulations, in 1797 was passed on to her daughter who received it until 1813, the year she married Karl Hönig.

- Landstraße No. 224 was not "a large house". It was rather small. The Danish actor Joachim Daniel Preisler did not visit the Mozarts in 1787 at Landstraße No. 224, but in 1788 at Alsergrund No. 135.

- Nannerl Mozart did not "retain all the valuable gifts given to the young Mozart". The list, which was drawn up on the occasion of the auction of Leopold Mozart's belongings, proves that those gifts had been sold by Leopold many years earlier. Selby's description of the distribution of Leopold Mozart's estate is based on Solomon's erroneous speculation and is therefore completely false. Nannerl did not "receive 6,000 to 10,000 florins from her father". As I explained in detail in 2012, Solomon's theory is based on a miscalculation of Nannerl's heritage from her husband, who not only bequeathed to his widow an annual pension of 300 gulden from the interests of her children's share, but also the main share of his estate of 22,000 gulden. Selby's descripton of the events after Leopold's death is rife with unfounded speculation and – as always – driven by hatred against all of Constanze's "less well-meaning" contemporaries. That Mozart "received punishment through Leopold's will" is a classic "Selbyism". Selby is ignorant of the sources and the literature dealing with Leopold's estate.

- Gluck did not receive "a lavish funeral." As a matter of fact, this funeral was performed "in der Stille" (without music) and only cost 28 gulden 49 kreuzer (of which 12 gulden were paid for the carriage with four horses to the Matzleinsdorf Cemetery).

- In 1787, Mozart did not earn "1,700 florins in Prague". This estimate is based on Maynard Solomon's flawed presumption.

- Selby writes: "On December 7, Mozart was appointed to Gluck's vacated position as Chamber Music Composer to the Viennese Court" (p. 86). No, he was not. a) Gluck's position was not that of a "Chamber Music Composer to the Viennese Court". Gluck held an honorary position as a supernumerary which also explains his high annual salary of 2,000 gulden. b) Mozart was not appointed "Chamber Music Composer", but "k.k. Kammermusikus" which is a huge difference and explains the modest annual salary of 800 gulden that came with that position.

- That Mozart's begging letters to Puchberg are proof for his poverty in 1788 is an out-dated point of view. At this time, Mozart was living in a 300m2 apartment for which he paid an annual rent of 250 gulden. He also owned a horse and a carriage. Of course, he shamelessly took advantage of a well-to-do brother Mason. The suggestion that Mozart's begging letters were mostly theatrical scrounging efforts (which I first published in 2012 in my review of Günther Bauer's book Mozart. Geld, Ruhm und Ehre) has been echoed by Nikolaus Harnoncourt in a 2014 interview, who (not surprisingly) disingenuously presented my concept as his own brilliant idea.

- Selby's account of the origin of Così fan tutte is based on the out-dated popular literature and is therefore worthless.

- "Theresia von Trattner stood godmother for the little girl and the christening took place in St. Peter's Church". As I have shown in 2009, Theresia Mozart's christening did not take place in St. Peter's Church, but in Mozart's apartment.

- Prince Lichnowsky's 1791 lawsuit against Mozart had nothing to do with gambling. As a matter of fact, gambling debts were classified as "Naturalobligationen" (so-called imperfect debt relations) and therefore their payment could not be claimed in a court of law. Debts incurred from illegal gambling, on the other hand, were legally void, i.e. they did not exist at all in the eyes of the law. Hence, they could not be considered "Naturalobligationen". On 20 February 1753, Maria Theresia had issued a Patent die hohen Spiele und Wetten betreffend, ruling that "von niemanden, was er auf Borg verspielet, es mag wenig oder viel seyn, dem Gewinner, wenn selbser schon derentwegen eine schriftliche Recognition in Händen hätte, etwas bezahlet, noch der Verspieler von einer Obrigkeit hierzu angehalten werden soll" ("Nobody, who has gambled away money, be it little or much, should be forced by the authorities to pay the winner, even if this person is in possession of a written recognition."). The only gambling contracts that were legally valid were those concluded in connection with legal gambling, such as the official state lottery. Selby's repeated description of Mozart's debts as having been caused by gambling is comparable to the plot of Groundhog Day transferred into late eighteenth-century Vienna.

- Walther Brauneis did not come across information "in a Logbook of the Special Courts of Aristocrats" (Selby will never understand the correct name of this source). The entry that Otto Mraz found (and Brauneis then mistranscribed and published with a wrong date) is located in the 1791 Cameralprotocoll (FHKA NHK Kaale Ö Bücher 94) of the I. & R. Court Chamber (today's Finanz- und Hofkammerachiv of the Austrian State Archives).

- The address "Schulerstraße 816" is wrong. Johann Michael Auernhammer was neither a nobleman, nor a wealthy merchant. Gottfried Ignaz von Ployer was not "a high official of the court". He was a minor "Hof-Agent" who, at the time of his death in 1797, was totally broke. Babette Ployer was not a "von Ployer".

- That in 1789 "the priest of the Church am Hof was able to administer an emergency baptism to Anna Mozart" is false. Selby does not know the sources, the literature, or any other documents related to this child's birth. Mozart's daughter Anna was baptized by the midwife.

- The idea that Mozart's mass K. 317 was performed at the 1790 coronation in Prague (as Selby claims on p. 97) has been soundly debunked by Mozart scholarship years ago.

- That "Die Zauberflöte embraced the philosophy of Freemasonry" (p. 101) is a popular misconception that has been refuted in several recent scholarly publications. Die Zauberflöte is not a cryptogram of Freemasonry, but a classic fairy tale opera. Its supposed relation to Freemasonry (which nobody ever noticed back in Mozart's days) is a creation of fanciful twentieth-century writers.

- In summer 1791, in Baden, Constanze was not – as claimed by Selby – "again housed on the first floor above the butcher's". This error is one of the most ancient "Selbyisms", mostly because for years, Selby has relentlessly been repeating it on several online forums. In his letter to Anton Stoll of May 1791, Mozart expressedly referred to Joseph Goldhann's former apartment on the ground floor: "das nothwendigste aber ist; daß es zu ebener Erde seye [...] zu ebener Erde, beym Fleischhacker". Because of her bad feet, Constanze could not live "on the first floor above the butcher's", but had to use the apartment beside the butcher's.

- The estimation (copied from Solomon) that "Mozart in 1791 earned 5,000 florins" is of course pure hogwash. The rent for Mozart's apartment at the Camesina house was not "320 gulden for six months" (p. 63). It was 450 gulden for one year.

- The claims that "Süssmayr had a gift for composing in the style of famous composers" and that "Süssmayr composed numerous ballets which often lasted for three hours and were performed by the monks" (p. 106) are two other priceless "Selbyisms". That Franz Xaver Süßmayr "died of alcoholism" – as Selby impudently states – is nothing but slanderous malarkey. All surviving documents prove that Süßmayr died of tuberculosis.

- Selby claims that "for La Clemenza di Tito Mozart was paid 1,150.gulden[!], including expenses" (p. 107). This alleged fee is an old myth, based on Mozart's claim in 1789, that he was offered "200 Dukaten und 50 Dukaten Reisegeld" for an opera. But there is absolutely no proof that Guardasoni ever made that offer in 1789, and even less, that Mozart actually received this amount in 1791.

- "Many of Mozart's Zettel were found among Süssmayr's papers in the Hungarian National Library." (p. 162). No, they were not.

- Not "Jakob Haibel's father had been a tenor in the Schikaneder Company", Haibel himself had been that tenor.

- Like countless amateur Mozart writers, Selby is unaware of the fact that the name of Mozart's last child was not "Franz Xaver", but Wolfgang. The names "Franz Xaver" only appear in the baptismal register and were never used by the parents. Mozart's last child was always called Wolfgang or "Wowi" by his parents and the claim (appearing all over the popular literature) that Constanze "later changed his Christian names" (p. 34, 163, 250 and 253) is simply false. Selby's claim that "Franz Xaver[sic!] inherited from his father his malformed left[sic!] ear" is just too funny to be commented on.

- On 4 December 1791, Dr. Closset (which one of the brothers, Nikolaus or Thomas?) was of course not "enthralled by Die Zauberflöte that he refused to come". Closset came from the Burgtheater where Die Zauberflöte was not performed.

- Mozart's belongings were not "catalogued and assessed for taxation purposes", but to secure the assets for the claims of the creditors. Mozart's debts with Lichnovsky, Puchberg, and Lackenbacher were not included in the official records, because "Constanze did not include them in her list prepared for the public records" (as Selby claims on p. 118), but because these creditors did not come forward to file their claims with the Vienna municipal civil court. A widow had no right to determine what the Sperrskommissär put on the list of passiva of her deceased husband.

- There was no such name as "Walsegg von Stuppach". The correct name is "von Walsegg". Walsegg did not commission "Johann Martin Fischer to create a tomb". He commissioned the sculptor Benedikt Hainrizi to do this.

- Selby's bizarre presentation of Franz Schubert as "poor, lonely young man who had struggled in a Vienna barely aware of his existence [...]", and who "had died young and of syphilis[sic!]" (p. 119) makes us very glad that Selby has refrained from writing books about other famous dead people.

- Selby's claim that Constanze "was listed in the Vienna Archives[sic!] as living in the Palais Liechtenstein in the Dorotheergasse which was near the Michaelerplatz" (p. 147) is just a conglobation of errors. There is no "Palais Liechtenstein" in the Dorotheergasse. Selby seems to have mixed it up with the Palais Dietrichstein, where Constanze also never lived. Constanze resided in the Palais Eskeles which is not located near the Michaelerplatz. Wetzlar von Plankenstern's villa in Meidling was not located "on the Grünberg", but at the bottom of this hill, above the so-called "Steurer Mühl Fahrtweg".

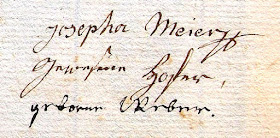

- The spelling "Friedrich Sebastian Mayer" is wrong. This singer and his wife always signed their names Meier.

- Constanze Mozart and her second husband did not get married in Pressburg, because she and Nissen fled from Napoleon's army or wanted to "wait for the storm to blow out". As a matter of fact, in 1809, Pressburg was bombed by Napoleon's army. They went to Hungary, because only there could they get the permission for an interfaith marriage.

In the chapter "Constanze's Second Widowhood" Selby falls into a well-known trap that regularly claims victims among all kinds of enthusiastic amateur Mozartologists: she actually thinks that Leopold Mozart, Euphrosina Pertl, and Genoveva Weber were all buried in the family grave in the cemetery of St. Sebastian in Salzburg. And yet, it has been known for decades – based on the Berchtold von Sonnenburg family papers in Brno – that Leopold Mozart (just like "Theophrastus Paracelsus" as Selby hilariously misnames this historical figure) was not buried in the churchyard, but in the communal crypt of St. Sebastian. The "Mozart family grave" in this cemetery is an artificial site, created by Johann Evangelist Engl for reasons of nostalgia. There were no family graves in today's sense in the eighteenth century. The whole defensive rant, brought forward by Selby against "attacks by Mozartean writers accusing Constanze of desecrating Leopold Mozart's grave by having her aunt Genoveva buried there" is based on ignorance of the literature.

To defend Constanze's absence from her husband's burial, Selby resorts to Philippe Ariès's book Images of Man and Death, but her discussion is completely beside the point. The main issue was not "the wife's place in her home and not at the burial", but the customs related to Josephinism. Constanze was not "forbidden to attend Mozart's burial", she did not even consider to attend it, because it was not customary. At that time, the act of burying a body was no part of the Christian rite as it is today. People bid goodbye to their loved ones at the church and not in the cemetery, a custom that only began to change in the course of the Napoleonic Wars. Selby's musings about "the United States changing western attitudes toward death in the 20th century" (p. 114) have nothing to do with the relevant issues of eighteenth-century cultural life in Vienna. Because Selby is totally ignorant of the intricacies of the Josephinian burial regulations and their partial repeal in 1785, she rehashes all the nonsense about "Mozart having been sewn into a linen sack and having been buried with a reusable coffin". These old misunderstandings have all been refuted and should certainly not resurface in a 2013 publication. Not "eighty-five percent of Vienna's citizenry" received a third-class burial, but ninety-nine percent. Selby extrapolates from a small section of the St. Stephen's burial records which does not represent the situation in all of Vienna's parishes. First-class burials were not (as Selby presumes on p. 117) "reserved for the nobility", but for anybody who was willing to pay for them (this old misunderstanding seems ineradicable). Because Selby's description of the funeral classes is copied from the worst secondary literature (such as Brendan Cormican), it is totally flawed.

Selby repeats her old story about Süßmayr's supposed trip to Kremsmünster Abbey in December 1791, and that after Mozart's death, "Süssmayr was nowhere to be found" (p. 128). Over thirteen years ago, Selby already posed as omniscient archival researcher on public internet forums as follows:

I would like to add that I have serious doubts about Sussmayr working on the Magic Flute which Constanze sold for 100 ducats 23 days after Mozart's death. While working on my book, "Constanze. Mozart's Beloved", I came across Archival evidence at the Vienna National Library, in the archives of Kremsmunster Abbey wherein Sussmayr arrived at the Abbey on 17 December, 1791 in the company of Pater Pasterwitz. It had been Sussmayr's custom to spend Christmas at Kremsmunster where he organised the Christmas festivities. It is also the reason why Constanze could not find him, when pressured for the completion of the Requiem by Count Walsegg's representative and why the Requiem was first handed over to Joseph Eybler who signed for it on 21 December, 1791. Eybler found himself incapable of completing the Requiem and it was then given to Sussmayr on his return from Kremsmunster. I have not been able to find in the archives his departure date from the Abbey. [...] Some further information to iron out one more wrinkle posed by both Carr and Gartner[sic!], Constanze was NOT MAD AT SUSSMAYR when she could not find him after Mozart's death. She was looking for him to complete the Requiem and NOT TO MARRY HER. She could not find Sussmayr because he was at Kremsmunster Abbey making preparations for Christmas festivities which he did every year. Again Kremsmunster archives can be found at the National Library in Vienna. (Agnes Selby on www.openmozart.net, 28 December 2000)

My studies in the Vienna archives where all Baden records about the comings and goings to and from Baden record that on every occasion Sussmayr was in Baden he travelled with Pater Pasterwitz and not with Constanze. Sussmayr and Pater Pasterwitz were registered at a hotel, the name of which escapes me but if anyone is interested, I would be happy to go through my files. This is very important to understand in order not to perpetuate the lies created by Francis Carr and Heinz Gartner[sic!]. Neither of these two gentleman seems to have taken time for proper research. [...] I checked the Baden records at the Viennese National Library[sic!]. These are records of people coming and leaving Baden. I took as my point of departure the dates of Constanze's presence in Baden. [...] Sussmayr seems to have led a good life, e.g. his trips to Baden. These may have been paid for by Pater Pasterwitz in whose company he travelled. (List of Arrivals and Departures. Baden police file in Archives, Austrian National Library, Vienna).

After Dan Leeson, in 2006, had somebody search in vain for these sensational "police records", Selby simply relocated their alleged place of discovery to the Baden City Archives.

Police files from Baden indicate the arrival of Pasterwitz and Sussmayr on at least three occasions and staying together at a hotel in the township. These files are available to researchers in the Baden city archives. (Agnes Selby, 23 November 2006)

As for the Police Files, I know, Mr. Lorenz has had a field day telling me that they do not exist and that they were burnt in a fire. Mr. Lorenz, you know perfectly well that this is not true and the files do exist. Somewhere you have got all this mixed up as the police files rest comfortably in the archives of the Austrian National Library. (Agnes Selby, 17 August 2008)

Agnes Selby's fictional sources are not limited to Süßmayr's life. Concerning Mozart's commemorative service, which Emanuel Schikaneder organized on 10 December 1791, she claimed to have received a letter from St. Michael's Church in Vienna.

I wrote to St. Michael's Church and received a polite reply informing me that the singers were listed in the Church records as well as the payment they received from Schikaneder who had organised this Commemorative Service. Although it has often been stated that parts of Mozart's Requiem were performed, I was told that there is no record as to the music performed. (Agnes Selby, 14 August 2008)

I wrote to St. Michael's Church and was told that although a list of performers exists in the archives of the Church and even how much they were paid, whose Requiem was performed had not been noted. I sent this letter to Dr. Zaslaw who had the same information sent to him. (Agnes Selby, 9 August 2007)

Well it must have been a "ghostie" who wrote to me and to Dr. Levine that the list of performers at St. Michael's Church exists but not what was peformed on that crucial night. (Agnes Selby, 17 August 2008)

Morgan Flannery lives in London where he has a teaching job. The last I saw him was over a capuccino at the Sydney seaside suburb of Woolloomooloo, where good capos can be found. Morgan has since his Prague adventure got married and has to now "earn his crust". It is true, he has yet to present his findings but I did not realize it was my duty to inform you of his inability to complete his thesis in time. You see, the Lichnowsky files were indeed burnt during World War II by the Germans, and information is difficult to find although he has a good bit of material available. The Germans did a lot of damage to beautiful Prague!!! As a very young and enthusiastic warrior of that era, you must remember it well. (Agnes Selby, 17 August 2008)

Selby's book presents a grossly overoptimistic, untrue, and apologetic picture of Constanze Mozart as a flawless saint. This does not correspond to the current state of research and is caused by Selby's only rudimentary knowledge of the scholarly literature. The reissue of Selby's book is a regrettable waste of money and paper. This book has not even come close to an expert musicologist's proofreading eyes, and there is ample reason to presume that not even the publisher bothered to read it with adequate attention. It is a real pity that Selby was unwilling to completely overhaul her work. So many interesting topics related to Constanze Mozart are still waiting to be explored more deeply: Where and when did Constanze move after Mozart's death? Where exactly did Nissen live in Vienna? Why did Constanze reject Schwanthaler's first design of her husband's statue? Who destroyed the many letters of Leopold Mozart? Who is the woman on the supposed "photograph of Constanze Mozart" that, for simple technical reasons, cannot originate from before 1842? What about the early musical career of Karl Mozart who in many Viennese sources is being addressed as "Tonkünstler"?

Wir sehen voraus, daß wir auch manchmal in den Fall kommen werden, daß ein Liebling der Menge nicht gerade auch unser Liebling sei und wollen die deshalb unvermeidlichen Vorwürfe gern über uns ergehen lassen.

(Goethe: Über strenge Urteile)

© Dr. Michael Lorenz 2014.

Updated: 8 November 2024

.jpg)